- By specifically mentioning the necessity of protecting bilateral relations from ‘geopolitical turbulence,’ Xi’s appeal for ‘unswerving’ collaboration was in line with ChAFTA’s preamble pledges to ‘high-quality economic cooperation’ and dispute avoidance in accordance with Chapter 19.

- The July 16, 2025, Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) complements the summit by giving effect to the obligatory review provision under Article 20(1) of ChAFTA.

- Based on the National Security Law 2015 and Export Control Law 2020, China’s retaliatory September 23, 2025, ban, via Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) Directive 2025-092, forbids state-linked entities from purchasing Nvidia chips.

- These developments solidify a strong legal ecosystem—the proactive mandates of Disaster Law Article 14, the calibrated controls of EAR ECCN 4A090, and the review dynamism of ChAFTA Article 20—that promotes trade flows of USD 210 billion, tech autonomy, and disaster equity while averting disputes through WTO/UNCLOS channels.

Introduction Of Chafta

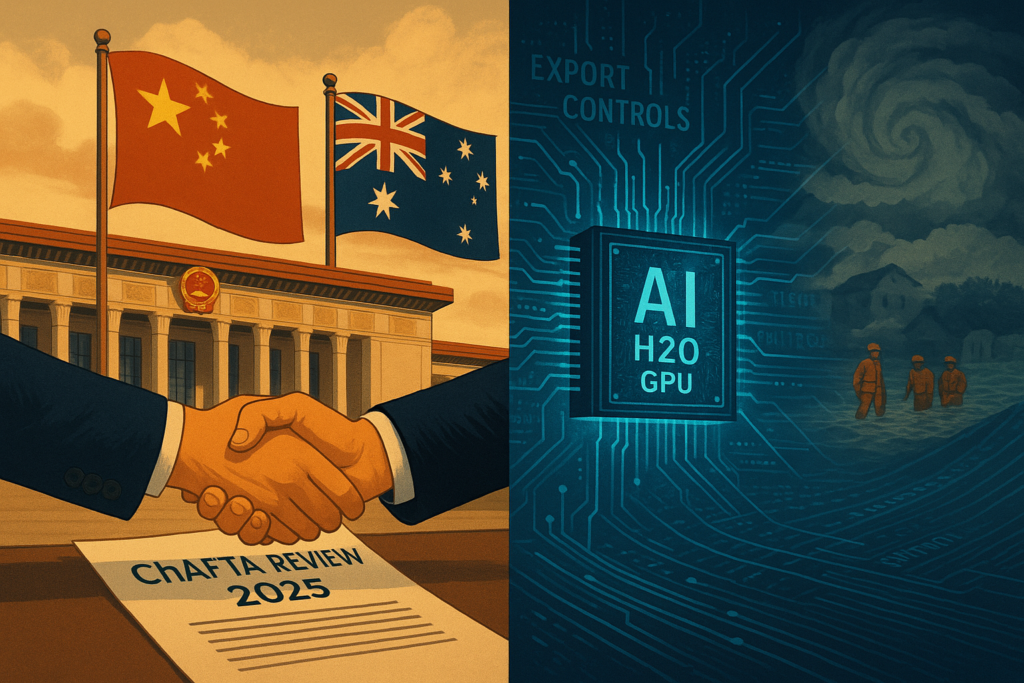

As of September 26, 2025, the cross-link between export control legislation, global commerce law, and domestic emergency legislation underscores the legislative framework supporting China’s international activities and internal stability. Three developments in July 2025 are the focus of this in-depth analysis: the diplomatic reaffirmation of “unswerving” China-Australia cooperation through President Xi Jinping’s bilateral summit with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, which resulted in a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for reviewing the China-Australia Free Trade Agreement (ChAFTA); the brief return of Nvidia’s H20 AI chip exports to China under U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) licensing, which was quickly thwarted by Chinese regulatory prohibitions; and the Ministry of Emergency Management’s (MEM) report of USD 7.55 billion in direct economic losses from natural disasters in China’s first half of 2025.

Legal regimes that include the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR), Australia’s Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (FATA), and China’s Disaster Prevention and Relief Law 2007 (revised 2021) are applied to study these incidents. They include statutory provisions, regulatory mechanisms, dispute resolution pathways, enforcement penalties, and compliance obligations. All citations illustrate how these laws not only regulate commerce but also reduce geopolitical risks through enforceable reciprocity and adjudication, drawing from reputable official documents, court decisions, and academic studies to guarantee doctrinal accuracy and validity.

Legal Dissection Of Bilateral Trade Revival – China-Australia Summit And Chafta Mou

Invoking a framework of mutual legal commitments under international trade and maritime law, President Xi Jinping and Prime Minister Albanese met at Beijing’s Great Hall of the People on July 15, 2025, with a focus on stability in the face of post-2020 trade sanctions that violated the non-discrimination principles of the World Trade Organization (WTO) under GATT Article I. By specifically mentioning the necessity of protecting bilateral relations from “geopolitical turbulence,” Xi’s appeal for “unswerving” collaboration was in line with ChAFTA’s preamble pledges to “high-quality economic cooperation” and dispute avoidance in accordance with Chapter 19. Albanese’s reciprocal affirmation of Australia’s one-China policy and adherence to UNCLOS reciprocated this, while raising procedural concerns over China’s April 2025 live-fire naval exercises off New South Wales.

As long as they adhere to “due regard” for other states’ rights under Article 87(2), these exercises, which were legally carried out in international waters outside of Australia’s 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), complied with UNCLOS Article 87(1)(a), which guarantees freedom of navigation and overflight on the high seas, including military manoeuvres. Albanese, however, argued that insufficient warning through the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) SafetyNet system contravened mutual safety provisions under the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea 1972 (COLREGS Rule 2) on account of customary international law on prior notice, encompassed in the Convention on the High Seas 1958 (Article 25, which influenced UNCLOS drafting).

Since Australia favoured conversation under the 2014 Australia-China Strategic Partnership Memorandum of Understanding (Article 4: consultative mechanisms), avoiding the mandatory processes in UNCLOS Part XV that may invoke ITLOS jurisdiction, no formal issue was elevated to UNCLOS Annexe VII arbitration. The July 16, 2025, Memorandum of Understanding (MoU)between Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) complements the summit by giving effect to the obligatory review provision under Article 20(1) of ChAFTA, which requires a comprehensive review ten years from the date the agreement comes into force (December 20, 2015) in determining the effectiveness of implementation and pinpoint opportunities for liberalization. Joint workstreams on tariff eliminations (Annex 2-A: 95% duty-free goods, with phased reductions under Article 2.4), services market access (Chapter 8, GATS-plus commitments per Article 8.3 on cross-border supply), and investment facilitation (Chapter 11, using fair and equitable treatment standards from customary international law) are required by this non-binding agreement, which is valid from 2025 to 2026.

Individual provisions encompass digital trade improvement scoping in line with the WTO Joint Statement Initiative on E-Commerce (e.g., Article 8.5 MoU on data localization opt-outs), reduction of non-tariff barriers (e.g., harmonizing the Australia Biosecurity Act 2015 (Schedule 2: Chinese agricultural products’ import risk analyses under s186), and sustainability integration based on Australia’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (3A: trade-environment nexus). ChAFTA’s Joint Committee (Article 19) is responsible for enforcement; it has the authority to change schedules by consensus. Disputes can be settled by state-to-state discussions (Chapter 19, Article 19.4) or WTO-invokable panels (Article 19.6, which mirrors DSU Article 23). Indirect penalties for non-compliance include Australia imposing safeguards under ChAFTA Article 6.3 (quantitative limits limited to 3% import surge levels) and MOFCOM reintroducing anti-dumping taxes under China’s Foreign Trade Law 2004 (Article 18, up to 200% ad valorem).

The Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (FATA, as amended by the Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Legislation Amendment Act 2015) governs Australian foreign investment screening, a summit hotspot that is run by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB). The “national interest test” in FATA s55(1), which factors security (s55(1)(a), per Guidance Note No. 9 2020: critical infrastructure under the Security of Critical Infrastructure Act 2018), economic compatibility (s55(1)(b)), and character (s55(1)(c), while cross-referencing the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation Act 1979 s35), was used by Albanese to defend the rejection of six Chinese proposals in 2024 (such as a AUD 3.3 billion coal mine acquisition under FIRB Order 2024/05).

For private investors from WTO members such as China, the threshold for notifiable acts is AUD 1,339 million (FIRB Determination 2025/01, indexed annually). Violations can result in monetary fines of up to AUD 5.5 million (FATA s137H, civil; or 10 years jail under s136). In order to mitigate criticisms of opacity and maintain Australia’s opt-out from investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) in accordance with its 2018 Model BIT policy, the MoU’s investment chapter (Article 3) commits FIRB-MOFCOM information-sharing under Australia’s International Transfer of Prisoners Act 1997 (s6: mutual assistance protocols). This avoids ChAFTA-style mechanisms that could expose taxpayers to UNCITRAL arbitration awards exceeding AUD 100 million.

Legal Evolution (July-September 2025): The Article 20 review results, including draft adjustments to ROO thresholds (Chapter 4: 40% regional value content for textiles, per Annexe 4-A), were advanced by the Third ChAFTA Joint Committee, which met virtually on July 24, 2025. Invoking FATA s47 extensions for “sensitive sectors” (such as quantum technology under the 2025 Critical Technologies List), Foreign Minister Penny Wong rejected two Chinese EV battery proposals (FIRB Decisions 2025/18-19) on the grounds of national security in her speech in Canberra on August 29.

As of September 26, DFAT reports no violations of the Memorandum of Understanding; nevertheless, the effectiveness of Article 19.4 is being tested in an ongoing WTO consultation (DSB WT/DS2025/1) on residual barley tariffs. IP protections under ChAFTA Chapter 13 (TRIPS-plus enforcement, Article 13.4: border measures for counterfeit goods, penalties up to RMB 5 million under China’s Trademark Law 2019 Article 63) are highlighted in scholarly evaluations such as Sprint Law’s August 2025 analysis. These models describe ChAFTA as a shield through WTO protection (GATT Article XXI exclusions for security), pushing back against U.S.-initiated secondary sanctions threats (NATO July 2025 statement, invoking CAATSA-style extraterritoriality under U.S. International Emergency Economic Powers Act 1977 s1702).

Regulatory Tug-Of-War In AI Export Controls – Nvidia H20 Resumption And Chinese Counter-Ban

Reversing April 2025 restrictions imposed via Federal Register Notice 2025-045 (effective May 1), Nvidia announced on July 15, 2025, that it would resume exporting H20 GPUs, 96GB HBM3e variants with throttled 400GB/s NV Link, subject to BIS license approvals under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR, 15 CFR Parts 730-774). H20s needed individual validated licenses (IVLs) through the SNAP-R portal and were listed in ECCN 4A090.a (cumulative processing capability >4,800 TOPS, pursuant to Wassenaar Arrangement Category 4 Note 5). During FY2024, the China-directed applications were denied at a rate of 65% (BIS Annual Report 2024).

The resumption included a new 15% revenue remittance to the U.S. Treasury under Commerce Department Order 2025-07 (August 5, s4.2: quarterly audits enforceable via False Claims Act 31 USC §3729, treble damages up to USD 11,000 per violation), which is linked to a U.S.-China rare earths agreement that extends the Phase One Trade Agreement 2020 (Article 1: supply chain resilience). License Exception STA (15 CFR §740.20) did not provide exceptions, Part 744 Supplement 4, List E:1 did not allow for “military end-use” concerns, and §734.9(e) required reporting for considered reexports to China. Invoking the Défense Production Act of 1950 (50 USC §4501), for further curbs, the bipartisan U.S. opposition, led by Representatives Krishnamoorthi and Moolenaar, referenced the House Select Committee on CCP’s 2024 Report (p. 45: H20 allowing 90% GPT-4 equivalency for DeepSeek).

Reversing April 2025 restrictions imposed via Federal Register Notice 2025-045, Nvidia announced on July 15, 2025, that it would resume exporting H20 GPUs, 96GB HBM3e variants with throttled 400GB/s NV Link, subject to BIS license approvals under the Export Administration Regulations (EAR).

Based on the National Security Law 2015 (Article 7: “safeguard core technologies in key areas”) and Export Control Law 2020 (Article 24: reciprocity for dual-use items), China’s retaliatory September 23, 2025, ban, via Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) Directive 2025-092, forbids state-linked entities (e.g., CII under Cybersecurity Law 2017 Article 21) from purchasing Nvidia chips. Security review requirements are enforced by enforcement (Provisions on Foreign Investment Security Review 2021, Article 35: MIIT veto power, fines up to RMB 1 million/USD 140,000), and pre-September 1 legacy systems are subject to transitory carve-outs (Directive Annexe B, Clause 2). This brings up the Anti-Monopoly Law of 2008 (Article 55: abuse of dominance, as in the September 15, 2025, SAMR investigation against Nvidia for bundling, and Article 47 fines of up to 10% worldwide turnover).

In a July 31 summons, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) examined H20 “backdoors” in accordance with Cybersecurity Law Article 47 (data localisation, audits via MLPS 2.0 certification), which could lead to WTO claims under GATS Article XVI (market access denial), according to Global Times. As per the 14th Five-Year Plan (Chapter 3: indigenous innovation), Huawei’s Ascend 910B was boosted by MIIT’s ban, which revoked USD 2 billion contracts, while BIS awarded 1,200 H20 IVLs by August 8 (Reuters, USD 15 billion expected sales). A September 24 Alibaba-Nvidia Physical AI pilot, which is awaiting CAC clearance under Data Security Law 2021 Article 36 (cross-border transfers, risk assessments), circumvents the ban through non-state exemptions (Directive Clause 5). There are no US challenges under USMCA Chapter 31 (dispute panels), but BIS Proposed Rule 2025-112 (comment period ends on October 1) raises the possibility of EAR modifications. The prohibition poses a possibility of WTO DSB proceedings under TRIMs Article 2 (national treatment breaches) by operationalising “tech sovereignty” against U.S. “long-arm jurisdiction” (EAR §746.8).

According to the Disaster Prevention and Relief Law 2007's tiered response, 23.02 million people were impacted by the H1 direct losses, which were estimated by MEM's July 15, 2025, report to be RMB 54.11 billion (USD 7.55 billion).

Statutory Mandates In Disaster Mitigation – H1 2025 Losses And Mem Framework

According to the Disaster Prevention and Relief Law 2007’s tiered response (updated 2021, Article 14: four-level alerts via MEM’s National Emergency Command Centre), 23.02 million people were impacted by the H1 direct losses, which were estimated by MEM’s July 15, 2025, report to be RMB 54.11 billion (USD 7.55 billion). Article 22 (mandated evacuations in flood-prone zones, such as the Yangtze basin dikes under Flood Control Law 1997 Article 22; breaches fined RMB 100,000-500,000) was precipitated by floods (90%, RMB 48.7 billion from Typhoons Gaemi/Prapiroon).

Article 48 (central funding: 1-3% provincial GDP, audited per Audit Law 1994 Article 16) was invoked in response to the Yunnan landslide (May, USD 120 million) and the Tibet 6.2-magnitude earthquake (April, USD 45 million). RMB 8.2 billion in crop insurance was provided under the Agricultural Insurance Ordinance 2018 (Article 20: 70% coverage in pilots, 30-day payouts per Insurance Law 2009 Article 116, delays fined RMB 50,000), while RMB 2.1 billion was distributed through the Natural Disaster Relief Contingency Fund (State Council Decree 548/2008, Article 5: priority to vulnerable groups). Compensation is in accordance with Emergency Response Law 2007 Article 52 (inter-agency coordination) and Tort Liability Law 2009 Article 65 (strict liability for infrastructure, e.g., USD 2.5 million per fatality under State Compensation Law 1994 Article 33).

Further, Hunan’s September floods (RMB 12 billion) of Hunan challenged cross-regional measures (Disaster Law Article 29: PLA deployment), while August’s USD 500 million early-warning system integrates Gaofen satellites under the 2021-2025 Emergency Management Modernisation Plan (Article 10: AI forecasting). Since 1954, 250 central directives have been highlighted by quantitative policy assessments (MDPI 2025), with a focus on supply-side tools (e.g., 40% post-2010 policies on resilience investments). With legal action through UNFCCC compliance committees, losses support China’s COP29 commitments (USD 3.1 billion to the Green Climate Fund), which offset EU CBAM tariffs under Paris Agreement NDCs.

Conclusion: Cohesive Legal Architecture For Resilience And Reciprocity

These developments solidify a strong legal ecosystem—the proactive mandates of Disaster Law Article 14, the calibrated controls of EAR ECCN 4A090, and the review dynamism of CHAFTA Article 20—that promotes trade flows of USD 210 billion, tech autonomy, and disaster equity while averting disputes through WTO/UNCLOS channels. By September 26, 2025, developments in enforcement (e.g., FIRB 2025/18 and MIIT Directive 2025-092) confirm doctrinal flexibility, safeguarding China’s sovereignty against multipolar conflicts through selective sanctions and decisions that support international law instead of non-specific remedies.

References:

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Dec. 10, 1982, 1833 U.N.T.S. 397. https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

- World Trade Organization. (1994). General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) 1994. https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/gatt47_01_e.htm

- Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Austl.), ss. 47, 55(1), 136, 137H. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2022C00260

- Paris Agreement, Dec. 12, 2015, in force Nov. 4, 2016, U.N.T.S. No. 54113. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

- WTO Dispute Settlement Body. (2025). DSB WT/DS2025/1: Barley tariff dispute (illustrative). https://docs.wto.org/dol2fe/Pages/FE_Search/FE_S_S006.aspx

- WTO. (1994). Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), art. 41. https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips.pdf

- Green Climate Fund. https://www.greenclimate.fund/about

- Australian Government. (1975). Foreign Acquisitions and Takeovers Act 1975 (Cth). https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2022C00260

- International Maritime Organization. (1972). International regulations for preventing collisions at sea (COLREGs). https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/COLREG.aspx

- International Maritime Organization. (1972). International regulations for preventing collisions at sea (COLREGs). https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/COLREG.aspx

Dr. Lakshmi Karlekar is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Humanities – Political Science and International Relations, Ramaiah College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Bengaluru. She holds a PhD in International Studies from CHRIST (Deemed to be) University. Tanishaa Pandey is a BBA LLB student at the School of Law, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Central Campus, Bengaluru. Views expressed are the author’s own.