- Despite rules, local governments nevertheless employ coercive methods, recruiting civil workers, educators, and medical professionals to assist in cotton harvesting under penalty of termination or other disciplinary actions.

- The effectiveness of laws is weakened by systemic economic pressures from the state-controlled cotton industry, local coercion, and lax enforcement.

- This trend reflects the complex history in Central Asia’s cotton sector, which is still influenced by political reform initiatives, economic challenges, and international human rights demands.

- Cotton plays a role in India’s textile sector, sustaining millions of farmers and related enterprises, contributing around 4% to the total GDP and 30% to the agricultural GDP.

Historical Context and Evolution

Since the time of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, forced labour has been common in Central Asian cotton fields, especially in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Tajikistan. Despite advancements, public services, hospitals, and schools are still impacted by the recruitment of teachers, students, and civil servants to pick cotton during the critical fall season.

In an effort to cut back on American imports, the Russian Empire began cultivating cotton in Central Asia during its expansion in the 1860s. The regions that now make up Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan were able to become significant providers of cotton due to their rich land and ideal climate. The Soviet Union expanded Uzbekistan’s cotton monoculture and prioritised cotton production after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. The Aral Sea dried up as a result of extensive irrigation operations that used water from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers to facilitate this expansion.

Forced labour became widespread throughout the Soviet era. Millions of people, including children, college students, teachers, doctors, and other civil servants, were forced to pick cotton every harvest. Serious repercussions, including fines, losing one’s employment, or being expelled from school, followed repeated refusals to comply. Local authorities enforced predetermined output quotas under a state-directed system, frequently by coercion. President Islam Karimov upheld strict state control and imposed quotas upon Uzbekistan’s independence in 1991, thus continuing the practice of forced labour.

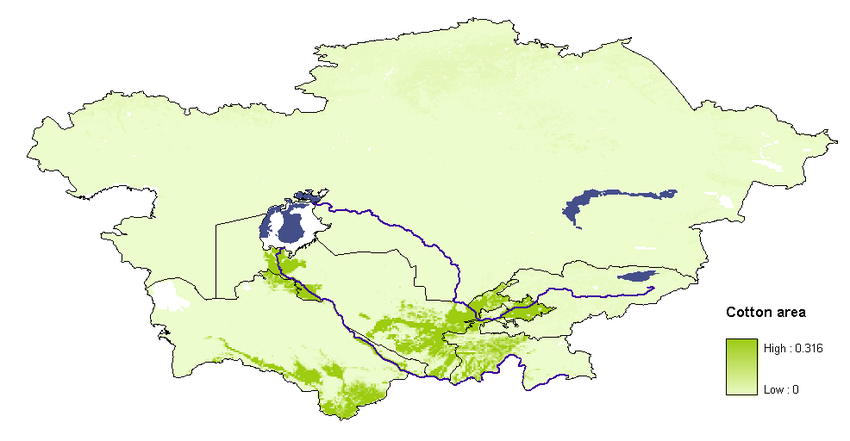

Figure 1: Cotton harvested areas in Central Asia

Source: (Aldaya, M. & Munoz, G. & Hoekstra, Arjen, 2010)

Recent Changes and Current Scenario

Forced labour was very common and cruel in the cotton fields before reform. Communities were recruited to work in dangerous conditions, particularly vulnerable groups like 10-year-old youngsters. Important services like healthcare and education were severely disrupted when public sector employees, including teachers, were put off. Families suffered financially because those who were forbidden from taking part had to pay bribes or hire labour substitutes to get out of the fields.

Cotton was considered “white gold” under this collectivised and coercive regime, which produced significant revenue for the state while maintaining farmers’ low wages and reliance on it. Local politicians and bureaucrats had a major role in establishing forced labour mobilisation with harsh penalties for noncompliance. High quotas and centralised administration were encouraged by the system, which paid little attention to worker welfare or human rights.

Under President Shavkat Mirziyoev, Uzbekistan has been implementing measures since 2016 to abolish child labour and forced labour in the cotton industry. Both the Soviet-style quotas and the mass mobilisation of students and public employees were formally abolished by the government. A cluster approach has reduced direct government intervention by largely privatising cotton production. Reforms, such as the implementation of independent labour monitoring and boycotts by large companies like Nike and H&M, were brought about by international pressure. In order to acknowledge the official eradication of systematic forced labour by 2021, the Cotton Campaign ended its boycott in 2022. The Uzbek government also supports the International Labour Organisation’s initiatives.

Workers in the vicinity of cotton fields describe living in subpar circumstances and working long hours for meagre pay, which is often deducted for housing and meals. Those who are unable to choose must frequently pay for replacements, which might consume a sizable portion of their monthly earnings. Human rights groups caution that as long as governments maintain centralised control over cotton prices and quotas, forced labour will persist despite reforms.

Why Was The Change Essential?

Forced labour systems have been partially dismantled as a result of international pressure, economic realities, and domestic political shifts. International boycotts and campaigns targeting supply chains associated with the suffering of child labour and forced labour compelled Central Asian governments to implement reforms. As international markets demanded ethically sourced cotton, privatisation and labour legislation changes were crucial for exporting nations like Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

President Mirziyoyev’s administration encourages domestic transformation to modernise the economy and enhance the nation’s reputation abroad. It is still challenging to alter the economically motivated coercion and the well-established centralised control of cotton production. In impoverished areas like Tajikistan, where local officials are still under pressure to meet output targets, the use of forced labour is made worse by low cotton prices and manpower shortages. Forced labour may persist in modified forms until the sector’s economic and governance institutions undergo profound reform. As a result, forced labour has complex legal repercussions that are intertwined with both national and international legal rules in Central Asian cotton fields, especially in Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Domestic Legal Framework

Uzbekistan’s constitution forbids forced labour, and new national laws have reinforced this prohibition. Amendments to the Criminal Code, the Labour Code, and the Constitution have expanded worker rights protection and strengthened punishments for forced labour offences. The Labour Code specifically forbids forced labour, which is defined as any job that is compelled under fear or without voluntary assent, with the exception of legally mandated military service or other alternatives. National institutions, such as a National Commission, have been established to track compliance, improve enforcement, and coordinate efforts to abolish forced labour.

Despite these rules, local governments nevertheless employ coercive methods, recruiting civil workers, educators, and medical professionals to assist in cotton harvesting under penalty of termination or other disciplinary actions. In Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, where there is weaker legal enforcement, it is still common practice to push public sector employees into cotton fields. Despite Tajikistan’s constitution’s prohibition on forced labour and hazardous work for children, abuses are nevertheless allowed because of lax enforcement.

International Legal Obligations: Challenges and Enforcement

Central Asian countries are bound by several international conventions aimed at eradicating forced labour and protecting workers’ rights, primarily through the International Labour Organisation (ILO). Uzbekistan and others have ratified key ILO conventions, including:

- Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29), which prohibits all forms of forced or compulsory labour;

- Abolition of Forced Labour Convention, 1957 (No. 105), which targets forced labour used as a means of political coercion or punishment;

- Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182), focusing on eliminating hazardous child labour.

These conventions require states to criminalise forced labour, establish mechanisms for its eradication, protect victims, and promote voluntary, fairly compensated work.

Enforcement remains the primary barrier, notwithstanding legal amendments. Many infractions occur as a result of pressure from local officials to satisfy cotton output requirements. Official denials notwithstanding, reports indicate continued coercion. International monitoring groups like the UN Human Rights Mechanisms and the ILO Committee of Experts, together with non-governmental organisations like Human Rights Watch and the Cotton Campaign, regularly criticise the inadequate enforcement of laws and call for increased state accountability.

Although officials who use forced labour have been penalised and fined, structural transformation has been slow because the cotton sector is still heavily regulated. This dynamic results in the unwilling conscription of public employees during harvest seasons; this is often camouflaged as “voluntary participation” but is actually enforced through threats. Furthermore, the lack of independent labour unions and free civil society organisations makes it difficult for workers to effectively demand their rights.

Geopolitical Implications and International Repercussions

Due to ongoing forced labour concerns, countries like the United States and the European Union have imposed import bans on cotton and textile products from states with documented forced labour systems. These legal measures aim to pressure governments to comply with both international law and global ethical standards in supply chains.

International financial institutions, like the World Bank, have also tied assistance to labour rights reforms, requiring anti-forced labour safeguards in projects related to the cotton sector. However, these measures have sometimes been undermined by weak governmental compliance.

Legally speaking, forced labour in Central Asian cotton fields is forbidden under both national labour and constitutional laws, as well as international agreements that these nations have ratified. Nonetheless, the ongoing use of forced labour highlights the stark differences between the law and reality. The effectiveness of laws is weakened by systemic economic pressures from the state-controlled cotton industry, local coercion, and lax enforcement. Long-term reform, better accountability frameworks, independent oversight, and international cooperation are needed to address the legal issues and align Central Asia’s cotton industry with accepted labour and human rights norms.

The existing sanctions concerning Xinjiang have disturbed sectors such as cotton and solar energy. Nevertheless, they have. Altered Chinese government policies did not benefit forced labour victims. This is partly due to the sanctions focusing on products rather than key organisations. They also overlook markets and suffer from unclear objectives. To be effective, the enforcing nations must explicitly outline the policy alterations they want from China. They should present reforms as a plan for sustainable progress and equitable trade. Additionally, they should focus sanctions on powerful companies that depend on capital, include nations affected by China’s unfair practices, and strengthen legal foundations, enforcement, business support, victim assistance, and coordination among governments and markets.

Starting in 2022, China emerged as Russia’s economic partner, offering markets, goods and crucial resources, whereas Russia predominantly delivers energy and raw materials. This bond is heightening Russia’s reliance. Despite growth in yuan-denominated deals and mutual trade, Chinese investment remains hesitant due to companies’ concerns about US secondary sanctions and the desire to preserve access to Western markets. This imbalanced partnership enables Russia to finance its war initiatives and circumvent sanctions. However, it also makes Russia vulnerable because an eventual peace agreement could leave it politically restricted and financially tied to Beijing.

This situation illustrates that sanctions are only effective when they are clear, swift, and supported by coordinated pressure on third countries. Otherwise, large global economies like Russia can adjust by turning to partners such as China, Turkey, or the UAE.

Western sanctions on China, like the US Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act and the proposed EU supply chain regulations, risk being ineffective. This is because businesses and governments lack clear information about who interacts with whom in international manufacturing networks. Researchers believe that the absence of an international “map” of these connections makes it very hard to track whether supplies involve Xinjiang or other risky areas. This situation renders trade laws based on human rights ineffective.

They suggest creating a secure, globally coordinated data-sharing system, possibly through organisations like the UN, IMF, World Bank, and OECD, to help monitor forced labour, environmental transitions, tax evasion, and supply shocks. However, political tensions, data sensitivity, and weak incentives to share information pose major challenges.

Export restrictions and sanctions from the US and its allies are currently changing supply chains, especially where they overlap with Xinjiang. These changes are forcing businesses to alter how they verify Chinese counterparts and inputs. The legal and operational risks of sourcing from key Chinese sectors, including cotton and silica-based products for solar and other industries, have increased significantly because of actions like OFAC sanctions on the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, CBP withholding orders, and the UFLPA’s assumption that goods tied to Xinjiang involve forced labour.

At the same time, a wider range of trade restrictions, from WROs to controls on “foreign adversaries,” is causing greater and more abrupt disruptions. This forces businesses to redirect trade, restructure financing, and sometimes abandon otherwise legal business due to moral, political, or reputational pressures.

China and Russia often use unilateral economic sanctions, but they tend to apply them in vague ways that differ from open, legally based penalties common in Western countries. A new dataset on 103 sanctions episodes (50 from Russia, 53 from China) reveals six methods of implementation, such as blacklists and bureaucratic obstruction. This study shows how both governments secretly restrict trade and investment while publicly claiming to resist unilateral sanctions.

China typically focuses on specific industries, like oil, coal, cotton, and rare earth exports, where a small number of state-linked companies can be influenced quickly. These methods may include sector-specific blacklists and coordinated consumer boycotts. In contrast, Russia often combines official counter-sanctions legislation with unofficial tactics such as targeted import restrictions. These strategies are usually presented as responses to Western actions and are first enacted informally before being formalised.

The key takeaway is that a nation’s vulnerability to Chinese and Russian sanctions depends more on its exposure to these subtle forms of economic pressure than on official measures. This complicates detection and responses, as well as standard assumptions about sanction design in Western studies and policies.

Why Does This Matter To India?

In 2023, the value of the cotton market in China and India was approximated at $16.5 billion. Forecasts indicate an increase with a compound annual growth rate of 3.8% reaching roughly $21.2 billion by 2030. This expansion is largely driven by the rising textile demand from the class and higher incomes in both nations. Cotton plays a role in their extensive textile and apparel sectors. Output, trade flows, and domestic prices are significantly influenced by global factors like price changes, currency rates, trade agreements, and demand from major importing countries, especially the US, Bangladesh, and Vietnam.

The market is inherently divided yet currently expanding, with regulations and technology being influencers. Both governments implement export and import regulations, quality benchmarks, minimum support prices, and subsidies to maintain farmer earnings and local supply. Additionally, they fund mechanisation and enhanced processing technologies to boost productivity, quality and sustainability. Xinjiang produces 90% of China’s cotton. Upland cotton, which supports its textile sector, dominates the market. Meanwhile, India is expected to grow more quickly due to initiatives like the Cotton Technology Mission, which aims to improve quality, reduce reliance on high-grade imports, and position the nation as a global sourcing hub.

Regarding the products, tree cotton is anticipated to expand the fastest because of its drought tolerance and significance in smallholder farming systems, especially in India. Conversely, upland cotton presently dominates the market share. It is vital to China’s contemporary production techniques. Medium-staple cotton is expected to experience growth as it underpins a broad spectrum of mass-market apparel and export-focused fabric manufacturing. Long-staple cotton is leading in revenue due to its quality for high-end textiles, such as Indian Suvin and high-grade Chinese products.

The paper additionally emphasises the challenges posed by substitutes that could diminish cotton’s market share due to factors like cost, effectiveness and environmental impact. These substitutes encompass fibres such as polyester and nylon, other natural fibres like wool and linen and regenerated fibres including viscose and lyocell. Key corporate entities in the China-India cotton value chain feature firms such as Cargill and Louis Dreyfus, along with textile companies, like Nitin Spinners and Changzhou Keteng Textile. They integrate cotton sourcing with spinning and fabric production, playing a key role in how changes in demand or policies are addressed.

5% of India’s farmable land is dedicated to cotton farming—primarily in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Telangana, which collectively account for nearly 70% of the total output—a SWOT analysis underscores its significance in the nation’s farming and industrial sectors. Cotton plays a role in India’s textile sector, sustaining millions of farmers and related enterprises, contributing around 4% to the total GDP and 30% to the agricultural GDP. Export levels fell in 2022-2023 after reaching a peak in 2021-2022 because of changes in global prices. However, they recovered in 2023-2024 due to increased global demand.

Strengths include a favourable climate, ample farmland, government assistance in the form of subsidies and minimum support prices, and research from organisations like CICR and ICAR. Weaknesses, such as dependence on unpredictable monsoons, limited irrigation, low yields, pest issues, high input costs, small land sizes, and insufficient use of machinery, hinder competitiveness. Environmental issues include groundwater depletion, pollution from fertilisers and pesticides, and vulnerability to climate change impacts like rising temperatures and erratic rainfall.

There are prospects in embracing farming techniques such as precision agriculture, improving seed quality and increasing organic and sustainable cotton cultivation, a field where India holds a leading global position. India could explore avenues to enhance value by upgrading processing methods and branding to meet the growing demand for friendly textiles. Nonetheless, risks to India’s exports arise from cotton producers using cutting-edge technologies and competition posed by synthetic fibres. Policy and regulatory challenges also arise from export subsidies under WTO scrutiny and shifting government policies that affect market stability and growth.

Overall, the essay stresses that maintaining and growing India’s cotton industry will require balancing technical advancements, sound regulations, sustainable practices, and addressing both local agricultural challenges and global market conditions.

The study uses spatial econometric models on provincial data from 1985 to 2021 to show how changes in factor prices, particularly rising labour wages relative to production materials and mechanisation costs, have greatly influenced China’s cotton production pattern. This shift has led to significant spatial clustering and a transition from the high-labour-cost Yangtze and Yellow River basins to the lower-cost, mechanisation-capable Northwest Inland region, including Xinjiang and Gansu, where cotton output is now dominant.

This shift is motivated by the difficulties involved in mechanising cotton farming. It restricts output in labour-divided areas while encouraging expansion in flat landscapes more compatible with machinery use. Significant spillover impacts occur as advancements in technology in one province improve specialisation in regions. These trends are also influenced by elements like calamities, irrigation extent, productivity and profit margins relative to cereals or oilseeds. When cotton profits decline, growers frequently shift to crops. The findings underline the need for policies that encourage automation, technology sharing, and regional collaboration to sustain China’s cotton industry amid rising input costs and global demands.

The global cotton market is significant as the main natural fibre, accounting for 25% of global fibre use and supporting 100 million households, mainly in low-income countries. The textile sector is worth about $1 trillion, with production stabilising at around 25 million tons annually despite disruptions from COVID-19 and other factors. There are balanced supply-demand dynamics, with forecasts of modest growth amid climate challenges and volatility due to events like the Russia-Ukraine war and US-China trade tensions.

Major issues involve poverty faced by small-scale farmers (who earn under 10% of the price, frequently less than their production expense of $0.46 per kg), dependence on substantial inputs (like pesticides and water), environmental damage, worries regarding forced labor (including prohibitions linked to Xinjiang affecting 80% of Chinas production) and rivalry from less costly synthetic materials. Climate change threatens production, with drought and heat stress, although cotton contributes to CO2 sequestration and provides mitigation opportunities through eco-methods. Cotton compliant with VSS standards (Better Cotton, Organic, CmiA, Fairtrade) represented 25-26% of output in 2019, worth $3 billion to $5 billion at farm-gate values. Despite expanding at a 39-40% pace between 2008 and 2019, the increase is now decelerating, including in producing countries such as India, the US and Brazil. Unfortunately, farmers frequently do not receive premium payments since around 25% of cotton is marketed as certified. Market distortions caused by subsidies are substantial, totalling $8 billion in 2019-2020 from China and the US. Fluctuations in prices related to the Cotlook A Index stem from demand shifts, weather variations, oil costs and geopolitical conflicts. Producers bear the risks, whereas retailers receive 40-50% of the value. Voluntary Sustainability Standards (VSSs) such as Fairtrade offer pricing and income advantages but need modernisation and greater transparency. Solutions call for long-term contracts with premiums that account for sustainability costs, adjustments in VSS pricing, direct sourcing with traceability, regional value chains, and policies to cut subsidies and distortions in order to improve farmer incomes, resilience, and sustainability.

Conclusion

Thereby, forced labour in Central Asian cotton fields resulted from coercive methods of the imperial and Soviet regimes. This system persisted after independence as a state-run enterprise that depended on widespread student and public worker mobilisation. Recent changes have reduced, but not eliminated, this behaviour, which continues to cause disruptions in the public, healthcare, and educational sectors. The trend reflects the complex history in Central Asia’s cotton sector, which is still influenced by political reform initiatives, economic challenges, and international human rights demands.

References

- International Labour Organization. (2023). In cotton fields: The ILO’s engagement in Uzbekistan.

- Anti-Slavery International. (2024). State-imposed forced labour in Uzbekistan: Progress and ongoing challenges.

- Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Research and Reports. (1999). Soviet cotton production in the postwar period [Declassified document].

- Pomfret, R. (2002). State-directed diffusion of technology: The mechanization of cotton harvesting in Soviet Central Asia. The Journal of Economic History, 62(1), 170-188.

- Aldaya, M. & Munoz, G. & Hoekstra, Arjen. (2010). Water footprint of cotton, wheat and rice production in Central Asia. Proceedings of The National Academy of Sciences – PNAS.

- Brackett, A. J., Rowan, J. P., Cowley, J. H., Marshall, L. C., Childs, E. O., Jr., & Baur, E. N. (2025). Analysing the impact of sanctions and export controls on supply chains. Global Investigations Review. https://globalinvestigationsreview.com/guide/the-guide-sanctions/sixth-edition/article/analysing-the-impact-of-sanctions-and-export-controls-supply-chains

- Cockayne, J. (2022). Making Xinjiang sanctions work (Policy Brief No. 10). Rights Lab, University of Nottingham. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/beacons-of-excellence/rights-lab/documents/xjaflcm/policy-brief-no-10-recommendations.pdf

- Ferguson, V. A. (2025). Putting your money where your mouth is not: China and Russia’s implementation of economic sanctions. Journal of Global Security Studies, 10(3), Article ogaf010. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogaf010

- International Institute for Sustainable Development. (2023). Global market report: Cotton. https://www.iisd.org/system/files/2023-01/2023-global-market-report-cotton.pdf

- India. Ministry of External Affairs. (2005). Report of the India-China Joint Study Group on Comprehensive Trade and Economic Cooperation. https://www.mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/6567_bilateral-documents-11-april-2005.pdf

- Ribakova, E. (2025). China-Russia cooperation: Economic linkages and sanctions evasion. Intereconomics, 60(2), 135–136. https://doi.org/10.2478/ie-2025-0025

- Zhang, X. W., Zhou, X. Q., Liu, H. M., Zhang, J. H., Zhang, J. D., & Wei, S. H. (2024). The impact of factor price change on China’s cotton production pattern evolution: Mediation and spillover effects. Agriculture, 14(7), Article 1145. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture14071145

- Human Rights Watch. (2017, June 27). “We can’t refuse to pick cotton”: Forced and child labor linked to World Bank Group investments in Uzbekistan.

- Chik, H. (2023, October 20). Scientists say Western sanctions against China ‘toothless’ without better supply chain data. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/science/article/3238540/scientists-say-western-sanctions-against-china-toothless-without-better-supply-chain-data

- Jalolova, S. (2025, September 12). Central Asia’s cotton harvest: Between reform, coercion, and economic strain. The Times of Central Asia.

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. (2025, November 2). Forced labor in Central Asian cotton fields disrupts schools.

- Freedom United. (2025, November 2). Central Asia’s cotton harvest still stained by forced labor.

Dr. Lakshmi Karlekar is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Humanities – Political Science and International Relations, Ramaiah College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Bengaluru. She holds a PhD in International Studies from CHRIST (Deemed to be) University. Tanishaa Pandey is a BBA LLB student at the School of Law, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Central Campus, Bengaluru. Views expressed are the author’s own.