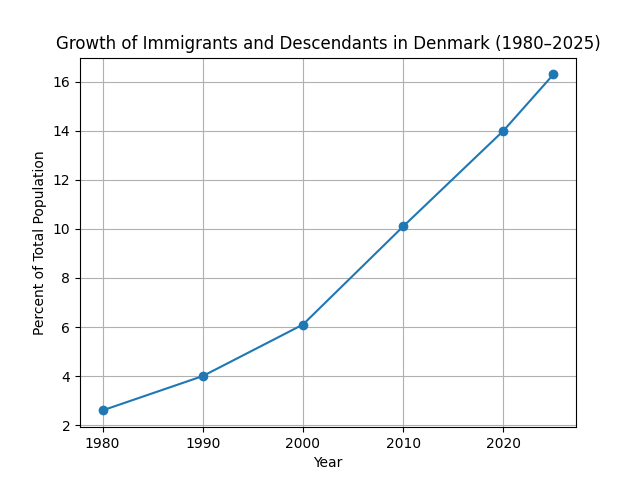

- In 1980, the number of immigrants constituted 2.6% of the total population of Denmark as a whole. In 2025, the number of immigrants stands at approximately 753,000, and also 224,000 Danes of immigrant parents.

- Over the past four decades, Denmark has evolved into a country characterised by high levels of immigration, diversity, and an increasingly activist state reaction to these challenges.

- In 2019, a temporary protection framework for refugees was officially introduced by Denmark, a move away from long-term settlement toward conditional stay.

- Denmark is moving past the traditional agenda of integration policies and advancing towards state power and securitisation strategies.

For most of the 20th century, Denmark was characterised by social homogeneity, strong trust in institutions, and a social welfare system founded upon common cultural premises. Meanwhile, there was some immigration, but its extent was modest. However, these conditions have now radically altered. Over the past four decades, Denmark has evolved into a country characterised by high levels of immigration, diversity, and an increasingly activist state reaction to these challenges. What sets the Danish case apart is not only its extent of immigration but also how effectively this has entangled issues with identity, social cohesion, and state sovereignty.

Denmark today finds itself at a crossroads. It currently has one of the most restrictive migration policies within Europe, despite the changing demographics. The conflict between openness and cohesion has come to define Danish politics.

From Homogeneity to Structural Change

In 1980, the number of immigrants constituted 2.6% of the total population of Denmark as a whole. In 2025, the number of immigrants stands at approximately 753,000, and also 224,000 Danes of immigrant parents, i.e., those having two immigrant parents. As of now, the foreign background people comprise 16.3% of the total population.

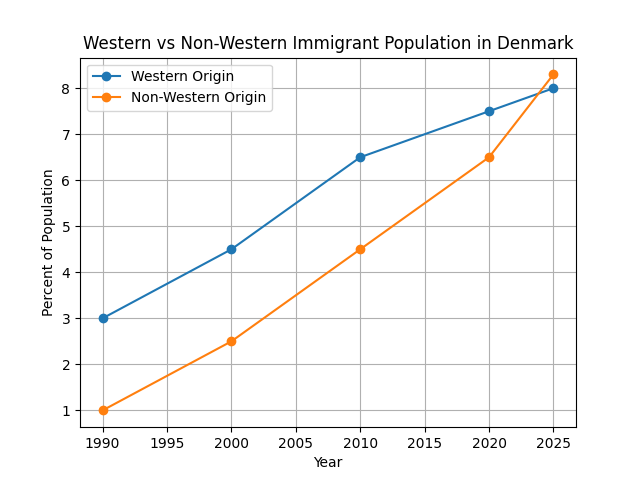

The immigration to Denmark was at first following some regional patterns. Nordic and Western European nationals were the main immigrants during this period, due to agreements on the mobility of workers and Denmark’s proximity to Western European Countries. Later, the composition of the immigrants to Denmark changed. The country involved itself in guest worker recruitment during the 1960s and 1970s from Türkiye, Pakistan, and the Former Yugoslavia. Others came due to conflicts in the Middle East, the Balkan regions, and Africa.

Though there is a significant number of immigrants from European states, the rise of the non-Western pattern of migration has been the more visible aspect of the issue.

Migration and the Welfare State Dilemma

The welfare state of Denmark is based on high taxation, wide redistribution, and public trust in institutions. This model presumes broad labour market participation and shared civic norms. Accordingly, immigration has been framed less as an issue of culture alone but more in terms of welfare sustainability.

From the early 2000s, access to permanent residence, family reunification, and citizenship has been tightened successively. Economic independence, competence in the host-country language, and employment have been made basic criteria. In 2019, a temporary protection framework for refugees was officially introduced by Denmark, a move away from long-term settlement toward conditional stay.

This direction of policy is widely politically supported. Unlike in many European states, restrictive migration policies in Denmark do not fall to the political right. Social democratic governments have actively defended strict controls as necessary to preserve the welfare model.

Spatial Concentration and Social Friction

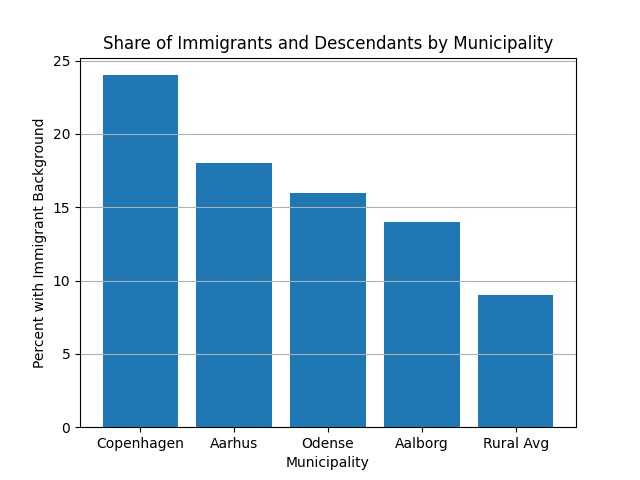

The data illustrate that immigrants and their offspring are dispersed unevenly among various municipalities, with a heavier presence in larger cities. Such distribution has fuelled discussions concerning integration with respect to housing, education achievement, crime, and cohesion.

The public policy has also targeted residential areas that have been considered socially disadvantaged. Such areas may have lower employment rates, lower incomes, and lower levels of educational attainment. Although communities have not been defined by religion in official statistics, such areas often include communities that have large proportions of non-Western-origin citizens. Such concentration has reinforced underlying themes of parallel societies and social fragmentation in shaping some of Denmark’s most provocative interventions in social policy.

State Power, Security, and the Ghetto Debate

Denmark is moving past the traditional agenda of integration policies and advancing towards state power and securitisation strategies. In the area considered disadvantaged, the state of Denmark practices extraordinary policies. For example, there are obligatory placements of children of immigrants in daycare, increased police presence, convicted criminals receive tougher punishment if the crime occurred within designated areas, and mass restructuring and destruction of public housing estates.

Muslim immigrants have become integral to this debate, not in terms of a legal definition but in terms of cultural reference. Denmark’s policy stems from the premise that integration needs to be imposed when voluntary integration fails. The idea of social cohesion is considered a matter of homeland security and thus requires coercive measures for its advancement.

What is peculiar to Denmark is that there has been a political will to legislate openly against residential concentration to the point where it has had to violate liberal standards hitherto typical of Western democracies.

Labour Needs and Policy Contradictions

Denmark has been experiencing an ageing society with an increased need for labour in the health care sector, care for the elderly, and in the technical fields. However, its immigration policy continues with a measure of deterrence as well as the temporality of stay. The country has adopted a selective immigration policy. Therefore, while easy immigration policies have been adopted in certain fields, humanitarian and family-based migration channels have remained closed.

Migrants are wanted as workers, but are not automatically wanted as full members of their adopted nation’s body politic. The integration that needs to take place is on a fiscal, not a cultural, level, as it is based on economic, not cultural, membership.

Identity as the Central Fault Line

Essentially, the migration discourse in Denmark is one of identity. The challenge is whether a society founded on cultural integration and trust can incorporate diversity without weakening the foundation. There is a growing notion in Danish integration policies that integration means adjustment to the norms.

Supporters claim that it secures gender equality, a secular state, and sustainable welfare systems. However, critics argue that it may institutionalise exclusions. There is no doubt that migration is a formative theme for the political future of Denmark.

Conclusion

The Danish experience is an important example of how a small welfare state copes with demographic transformation. Instead of either embracing or entirely rejecting multiculturalism, Denmark has adopted a model of controlled migration combined with enforced integration. Immigration is allowed, but highly regulated. Diversity exists, but within strictly set limits.

The question is whether this model will remain viable, given the way in which Denmark balances demographic reality against social cohesion in the decades ahead. Migration is no longer peripheral to Danish politics; rather, it’s central to the question of what Denmark is and what it seeks to become.

Tejashree P V holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from IGNOU and a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism, English, and History from Vivekananda Degree College. A UPSC aspirant, she has a keen interest in international affairs, geopolitics, and policy.