- Throughout the ages, wars, internal armed conflicts and large scale persecution has forced people to flee to places offering them safety.

- As India is not a signatory to the 1951 convention nor its 1967 protocol, it lacks a national refugee protection framework.

- The Assam accord promised to deport the illegal immigrants who had become an economic burden and were posing a challenge to the social fabric of Assamese society.

- India needs to adopt a comprehensive national policy for the refugees to provide safety and protection, legal safeguards, aid and funding from the state, welfare programmes for the refugees.

- As the circumstances in the contemporary Indian subcontinent have changed giving rise to two Islamic nations in India’s neighbourhood and the troubled historical baggage that confronts us today.

- Every persecuted Hindu and member of Indic religions such as Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism must be given a right to take refuge in India and become its citizen in the due course of time.

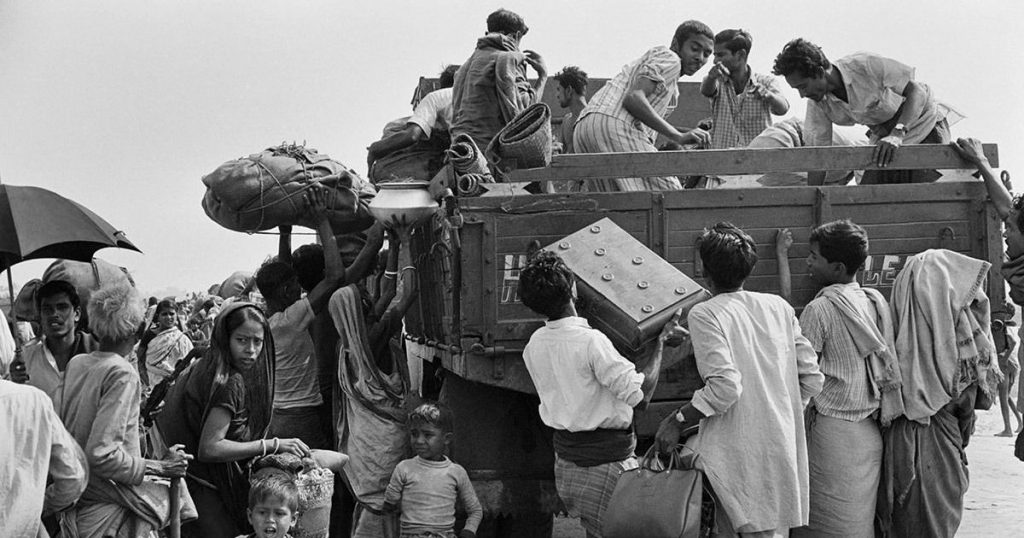

The Indian subcontinent has had a painful history of partition that had traumatised an entire generation of people, both from the eastern and the western side of the newly formed State of Pakistan. The tragic episode of the 1971 war and its fallout were no different from 1947-48. Millions of people, especially the Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs and Jains poured into Indian borders, millions were displaced and millions were killed. However, the irony is, we still do not have the official data of the exact number of refugees who came into India, and millions of people are living “Stateless” existence in inhuman conditions within the refugee camps. Ignorance of the Government, polarising politics by the political parties, civil society groups and NGOs who deliberately act oblivious to the dreadful conditions of the refugees living in India has furthermore aggravated the problem. Therefore it becomes very important to analyse the gravity of this crisis, to deliver justice to the refugees and stateless people who are sustaining their array of hope for several decades.

Historical background and the developments in the refugee issue

In 1947 when India attained its political freedom, it was partitioned and Pakistan was carved out on its eastern(present Bangladesh) and western front. The seeds of religious persecution were sown during those times leading to an outbreak of a series of communal riots across the borders and also had its footprints in the refugee camps. Especially in east and west Pakistan, wherein the State religion was Islam, as a brutal and atrocious unstated policy practice, all the religious minorities were persecuted. Rape, murder, robbery, dacoity and gruesome oppression of civil, political and economic rights were casual affairs. As this situation became worse the INC (Indian National Congress) passed a resolution on 25th November 1947which read as “The INC is bound to protect all non-Muslims, who have come over, crossing the borders or may do so, to save their lives and honour in the future; these people will be protected and given full citizenship in future”.

Moving ahead the Nehru-Liaquat Pact ( officially known as ‘Agreement between Government of India and Pakistan Regarding Security and rights of Minorities’ ) was signed between the Prime Ministers of Pakistan and India, Liaquat Ali Khan and Jawaharlal Nehru subsequently on 8th April 1950 and was an outcome of six days of talks which were sought guarantee the rights of minorities in both the countries after the partition of India and the advent of the war that took place in between. According to which Refugees were allowed to return to dispose of their property, the abducted women and looted property were to be returned, the forced conversions were unrecognised, and minority rights were fully confirmed, by this time close to 1.5 crore refugees had moved into India and among them, the majority were Hindus ( 99% Hindus from west Pakistan and 93% Hindus were from East Pakistan).

In 1981 it was estimated that around 80 lakh migrants were staying in India, mostly in Assam, West Bengal and Tripura.

Years later in 1971 in East Pakistan, as a result of the Bengali persecution on a linguistic basis, a civil war out broke between Mukti Bahini (a Bangla resistance outfit) and the State of Pakistan, India intervened in the war which led to full-scale conventional warfare, this led to the creation of Bangladesh. It’s important to know this, as the huge influx of refugees, most of whom entered illegally, took place this year and continued steadily in the next few years. In 1981 it was estimated that around 80 lakh migrants were staying in India, mostly in Assam, West Bengal and Tripura. In the year 1985 Assam Accord was signed between the Assam students Union and the Rajiv Gandhi Government with the main intention, to protect, promote, preserve and promote the cultural, social, linguistic identity and heritage of the Assamese people.

The Assam accord promised to deport the illegal immigrants who had become an economic burden and were posing a challenge to the social fabric of Assamese society and the cut off date was decided ( ie the date on or after which people would be declared as foreigners) was 25th March 1971. This accord was a result of the Assam agitation which was being fought from 1979, for the protection of Indigenous rights and Identity of the Assamese people. After years of delays and byzantine bureaucratism, under the monitoring of the Supreme court, the NRC exercise was carried out in Assam, Tripura and West Bengal mainly, and still remains an incomplete process. In Assam, the NRC process concluded that 19 lakh people are foreigners and out of them over 5 lakh happen to be Hindus.

The beneficiaries of the Citizenship Amendment Act 2019 identified so far

The Intelligence Bureau (IB) had submitted a report to the Home Ministry by identifying and calculating the number of beneficiaries of the erstwhile bill in 2016, which is enacted now. A total of 31,313 persons belong to minority communities including 25,447 Hindus, 5807 Shiks, 55 Christians, 2 Buddhists and 2 Parsis.

The IB had also said that ” for others (other than the minorities in these countries) to apply for the citizenship under this category, they will have to prove that they came to India due to religious persecution. If they had not declared so at the time of their arrival in India, it would be difficult for them to make such a claim now. Any future claim will be enquired into, including even the R&AW before a decision is taken.

(The above mentioned facts were revealed by the government, during a hearing by a parliamentary committee in the year 2016)

A few important provisions of International law and the need for a comprehensive Refugee policy in India

Throughout the ages, wars, internal armed conflicts and large scale persecution has forced people to flee to places offering them safety. Historical accounts relate many instances where survivors of war, religious persecution, natural disasters and other misfortunes were welcomed by other communities, given necessities such as food, shelter and clothing and were subsequently allowed to settle down in the new place. The UN General Assembly set up a Convention on 28 July 1951 to remedy agonies such as vast destruction of property, the pogrom against Jewish civilians and widespread homelessness that the civilian populations of Europe had suffered during World War II.

Humanitarian considerations, therefore, lay at the heart of the 1951 Convention. Although it was the intention of the international community to prevent such displacements in future, they continued to occur in other continents. This was why the UN General Assembly decided to expand the scope of the 1951 Refugee Convention by adopting the 1967 Protocol, to cover other parts of the world as well. The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 1951 is the foundation of international refugee law. It defines the term “refugee” as follows:

A refugee is someone who has a well-founded fear of persecution because of his/her

- Race, Religion, Nationality, Membership of a particular social group or political opinion;

- Residence outside his/her country of origin; and, Inability or unwillingness to receive any protection from his/her country, or unable to return home for fear of persecution.

A lack of understanding of refugee and statelessness issues among the local populations would pose a challenge to the vulnerable refugee communities.

It is important to understand the crucial difference between a refugee and a migrant. A refugee flees his /her home country to escape persecution or other tolerable conditions. A migrant shifts residence to another country to avail himself/herself of better earning capacity-an economically driven compulsion -as opposed to what effectively amounts to expulsion, in the case of a refugee. Persons who are yet to be formally accorded refugee status are generally described as asylum seekers. They are people who have fled their home country to seek shelter and protection in another country, but whose applications for grant of refugee status (being normally subject to a careful and often prolonged, case-by-case analysis) are still pending the approval of the authorities.

As India is not a signatory to the 1951 convention nor its 1967 protocol, it lacks a national refugee protection framework. This becomes an obstacle in providing proper and effective protection to the refugees. Moreover, a lack of understanding of refugee and statelessness issues among the local populations would pose a challenge to the vulnerable refugee communities. On humanitarian grounds, India has signed a few treaties for the protection of refugees and asylum-seekers. Article 14, 21, 22, 25-28, 32 and 226 of the Constitution guarantees protection to citizens and non-citizens through some of the rights that cannot be made into reality such as the right to self-employment and access to work if permissible. Such real practises are arbitrary in nature in all matters concerning refugees. India needs to adopt a comprehensive national policy for the refugees to provide safety and protection, legal safeguards, aid and funding from the state, welfare programmes for the refugees, education to the women and children, vocational training for their sustenance and so on and so forth. This would enable India to develop a proper institutional mechanism for its refugee population.

The case for India being a natural homeland for the vulnerable Hindus

The Indic civilization which is a cultural base for the Sanatana Dharma, known as Hinduism in modern times, has a recorded historical legacy of around 7000 years at least. The venerable heritage of our civilization and the cultural ethos that surrounded it had an intrinsic value of inclusivity, accommodation, mutual respect and acceptance of all the faiths and belief systems. Over the ages, the persecuted communities in the world, such as Jews and Iranians came to India to take refuge and the Indians accepted them with open arms showing benevolence to their apathy. Several travellers and religious saints have also echoed the sentiments of respect and acceptance Indians have always possessed because of their glorious civilizational legacy.

As the circumstances in the contemporary Indian subcontinent have changed giving rise to two Islamic nations in India’s neighbourhood and the troubled historical baggage that confronts us today, Hindus across the world should be considered as natural inheritors of our civilizational ethos. Both in Pakistan and in Bangladesh the Hindu population has come down radically, making the minuscule minority over there exposed to petrifying vulnerability. With 52 Islamic nations and 74, Christian/Christian dominated nations exist today. But the only country with a Hindu majority happens to be India. So, every persecuted Hindu and member of Indic religions such as Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism must be given a right to take refuge in India and become its citizen in the due course of time.

India, through its persistent value of eternal vigilance has never failed to deliver upon the progress of human endeavours, and by making India into a natural homeland for Hindus

Israel follows a similar model which considers all the Jews living across the world as its extended community who can take refuge in Israel at any given point in time. However there have been several arguments against this proposition, and one of the central “Concerns” is India becoming a regressive theocratic state which would trample against even the basic human rights of the religious minority. But it’s a well-known fact that except for a set of lunatic fringe elements, India’s minorities are safe and protected with equal constitutional status, and are given the fullest of rights and liberties as every other citizen enjoys. Not just political or legal rights, the Indian minorities have enjoyed equal social and economic rights and have lived here with peace and tranquillity for generations together. When the UK can be an Anglican Christian State with a Monarch as its head of state and possess the finest of liberal and democratic virtues, and when the USA can associate itself as a biblical promised land grounded upon the protestant Christian ethic and can accommodate plural ethnicities, why can’t India defend its illustrious civilizational legacy, by safeguarding its people who have no other option except taking refuge in India?

As the popular quote says, ” the price of liberty is eternal vigilance”. India, through its persistent value of eternal vigilance has never failed to deliver upon the progress of human endeavours, and by making India into a natural homeland for Hindus, it will certainly not fail in harnessing global harmony, peace and liberty.

Viswapramod is a PhD Scholar at the Department of International Studies and Political Science, Christ University, Bangalore. He has an MA in International Relations. Views expressed are the author’s own.