- In the last 35 years, the Indian defence sector has experienced a spectacular metamorphosis, moving from a military relying mostly on imports to a self-sufficient and strong defence industrial power.

- The period that began in 2014 witnessed incredible policy reforms that shaped the area of defence in India quite considerably.

- One of the most remarkable changes in India’s defence industry is represented by the huge increase in defence exports.

- India’s defence modernisation taking place over the period 1990-2025 signifies a changing of the guard from reliance to self-sufficiency.

Executive Summary

| In the last thirty-five years, the Indian defence sector has experienced a spectacular metamorphosis, moving from a military relying mostly on imports to a self-sufficient and strong defence industrial power. This comprehensive analysis examines the critical trends in defence procurement, indigenous production capabilities, research and development investments, and budget allocations from 1990 to 2025, revealing a strategic pivot towards Atmanirbhar Bharat (Self-Reliant India) in defence manufacturing. |

The Historical Context: 1990-2010

The Soviet Dependency Era (1990-2000)

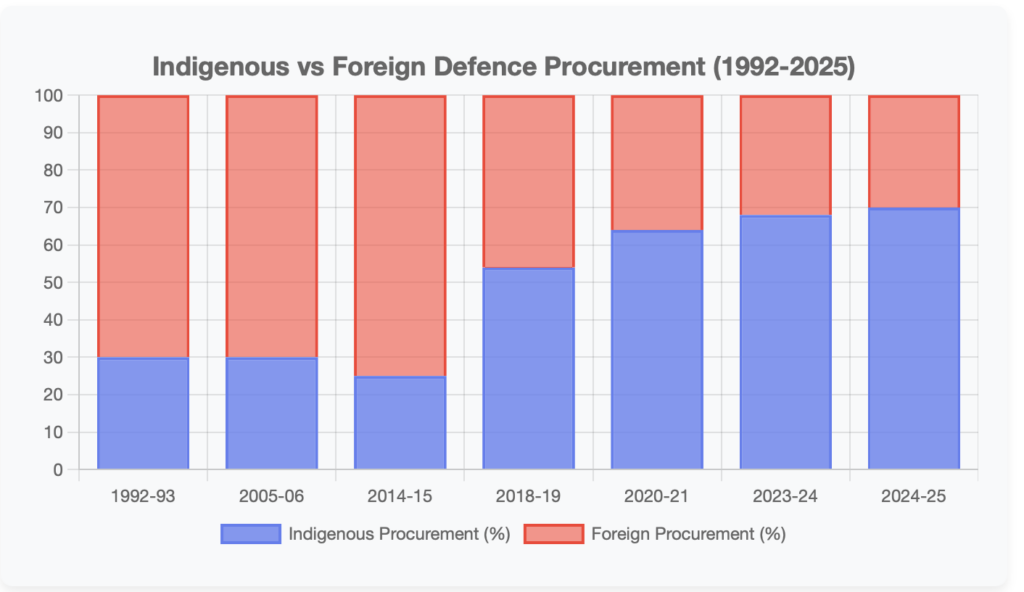

The downfall of the Soviet Union in 1991 was a watershed for the defence industry in India. India was, for a prolonged period, dependent on the Soviet Union as far as military hardware was concerned and had even manufactured some of the military equipment under the Soviets’ license. The 1962 dispute with China forced India to raise its defence budget to 2.3% of GDP; nevertheless, the nation had almost no (if any) capacities of its own to back up this cost. The Self-Reliance Review Committee, formed in 1990 by Dr A.P.J. Abdul Kalam, planned a detailed ten-year programme that aimed at increasing the Self-Reliance Index from 30% in 1992-93 to 70% in 2005.

However, the target was not met. The mid-1980s were a time when India’s defence production policy started changing, and the country was moving on from the license-based production to the R&D-oriented industrialisation phase, which was represented by the introduction of the Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme (IGMDP) in 1983. The project was assigned to develop the five missile systems: Prithvi, Akash, Trishul, Nag, and Agni. Nevertheless, despite these undertakings, the Self-Reliance Index remained approximately 30-35% for the entire 1990s, which was a clear signal of the challenges in growing local military capacities.

The Partnership Phase (2000-2010)

India understood that exclusively depending on domestic methods has its limitations, and thus, the country changed its plan by creating joint development and joint production partnerships with others. The 1998 India-Russia BrahMos supersonic cruise missile pact is an excellent example of this new line of thought. At that time, India was not only cooperating with Russia but also with Israel and France, all the while being the biggest military equipment importer in the world.

The Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP), which came into force in 2002, was the main factor that introduced clarity and regulation in the defence purchasing process, but the situation of relying on imports was still there. The Self-Reliance Index in 2006 was around the same level as it was in the 1990s, and this was mainly thereasone that India’s defence industry policy required to be changed radically.

The Transformation Decade: 2010-2020

Policy Revolution and Make in India

The period that began in 2014 witnessed incredible policy reforms that shaped the area of defence in India quite considerably. The launching of the “Make in India” programme and consequent “Atmanirbhar Bharat” schemes changed the battlefield of the defence industry dramatically. The establishment of the Indigenous Design, Development, and Manufacturing (IDDM) class in 2016 was the turning point where local design and production were preferred over imports.

Key Policy Milestones:

- 2016: Defence Procurement Procedure put in place “Buy (Indian-IDDM)” as the highest preference acquisition category

- 2020: Defence acquisition policy (DAP) 2020 was ushered in, along with automatic route liberalisation of FDI in the defence sector to 74%

- 2020: Import of 101 items announced as the first positive indigenisation list, banning the import of Defence items

- 2021: The second list added 108 more items, expanding it to over 5,500 items by 2025

Budget Allocation Trends

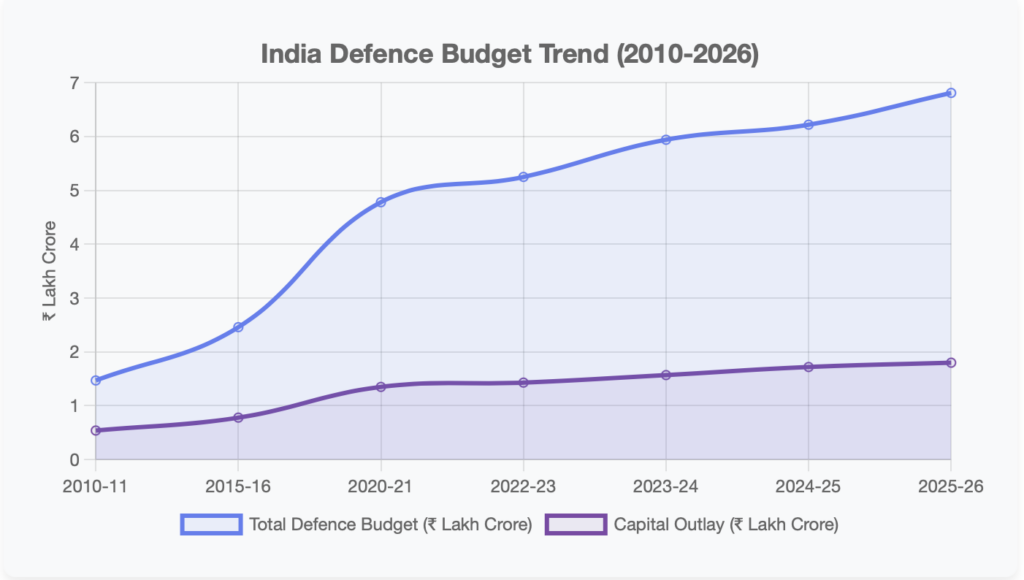

The Government of India increased Defence Spending dramatically from ₹5.94 lakh crore (i.e., approx.) or $85B USD in Fiscal Year (FY) 2023/24 to ₹6.81 lakh crore (approx. $96B USD) in FY 2024-25, which represents a 9.53% increase. However, the total defence expenditure share of GDP is less than 3% today, that is, approximately. 1.9% for FY 2024-25 vs. 3% in the 1960s. Because of these and other factors related to the global geopolitical stability, Strategic Analysts are concerned that India’s defence budget is insufficient.

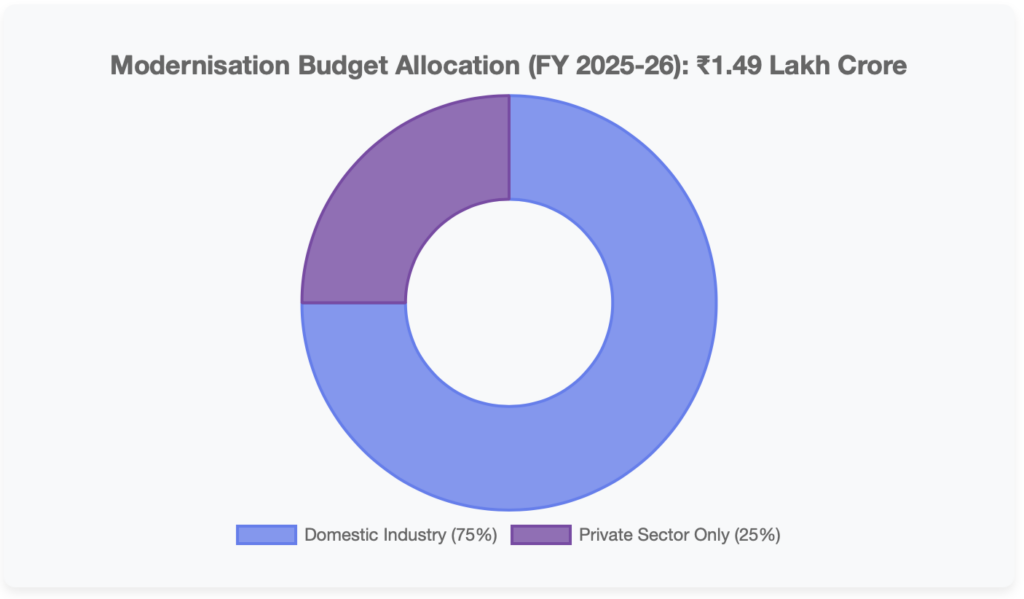

In terms of modernisation, the Capital Expenditure provision of ₹1.43 lakh crore (approx. $20B USD) for FY 2023-24 will grow to ₹1.80 lakh crore (approx. $25B USD) in FY 2022-23. Approximately ₹1.11 trillion will be spent on ₹1.80 lakh crore or 75% of modernisation via indigenous routes, and about 25% on the local Private Sector. This stands in stark contrast to the situation before 2014, where indigenous acquisition made up approximately. 25% of the total acquisition budget.

The Self-Reliance Index remained approximately 30-35% for the entire 1990s, which was a clear signal of the challenges in growing local military capacities.

Research & Development Investment Analysis

DRDO Budget Evolution

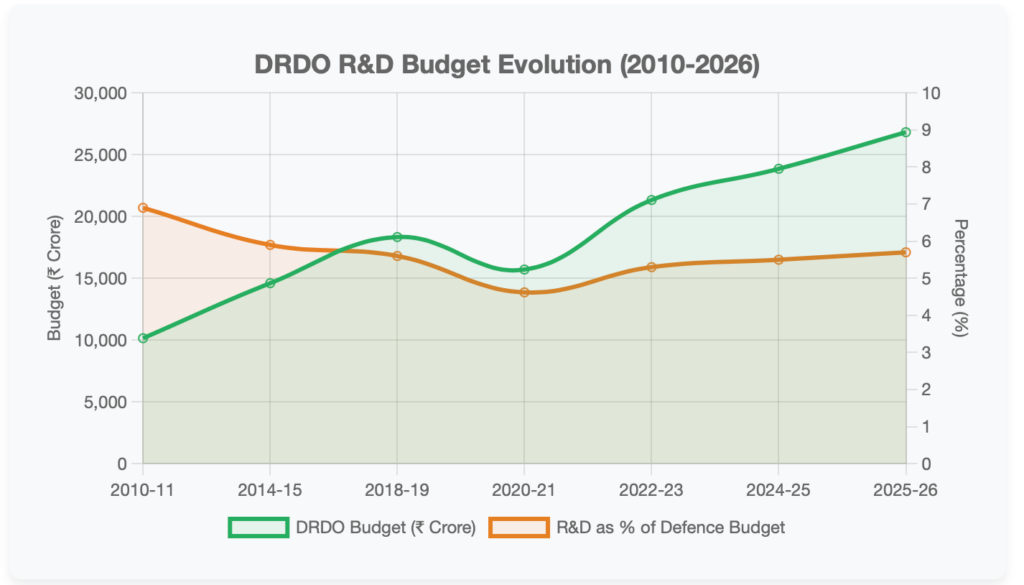

Founded in 1958, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has been acknowledged as the primary organisation for military Research and Development in India. The Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) has received a significant budget increase for the 2025-26 financial year from Indian rupees 10,149 crores to Indian rupees 26,816.82 crores, so the increase is a full 12.41% compared to last year’s budget. On the other hand, the share of R&D spending in total defence expenditure has experienced a substantial change and has dropped to its minimum level of 4.62% in the fiscal year 2020-21.

Approximately 30.7% of the total government R&D expenditure in India is covered by DRDO, which is the highest amount among the twelve leading scientific organisations. From the total budget of FY 2025-26, the major amount that is ₹14,923.82 crore will be invested in capital and R&D projects, which is going to strengthen the capability of DRDO to carry out next-generation technologies such as directed energy weapons, quantum systems, and AI under its DRDO 2.0 program.

| Critical R&D Gap: Indian defence industries spend only 1.2% of their revenue on R&D, which is a very low percentage compared to the global average of 3.4%. But the biggest exceptions are Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) and Bharat Dynamics, which are investing 9.3% and 6.1% respectively in R&D and therefore are the global leaders in R&D intensity. |

The Indigenous Production Revolution

Manufacturing Capability Growth

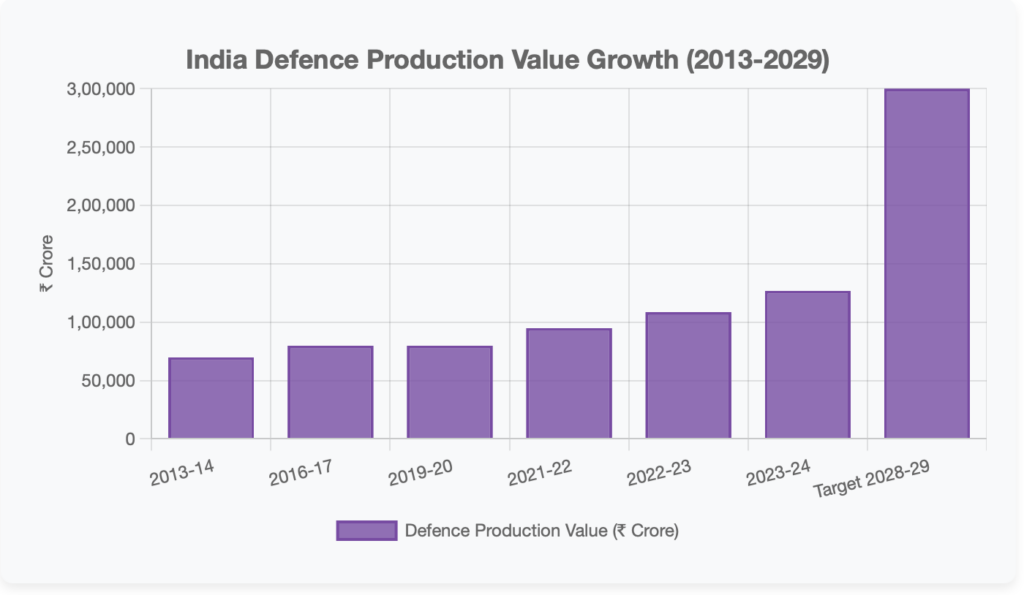

The Indian defence industry has seen a great boost in the last couple of years. India will see close to a 60% increase by FY 2023-24 since April 1, 2019, in Gross Output value from ₹ 70,000 crores year FY 2014 to ₹ 1,27,000 crores. The Indian DPSUs account for approximately 79.2% of the total cybersecurity, defence production and solution space of the country, while the private sector accounts for only 20.8% approx. The Indian Defence Force has established an ambitious target of a Production output of ₹1,60,000 Crores or ₹160 Billion by the end of FY 2025-26, and an even larger target of ₹3,00,000 Crores- ₹300 Billion by the end of the same fiscal year 2028-29 for Defence Production.

India is not only fully self-sufficient in its Defence Supply Chain but also has a Defence Public Sector Units (16) network. More than 400 Licensed Private Firms and/or Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) account for approximately 16,000 MSEs. Besides, these MSEs participate in the whole cycle of the most sophisticated technologies in the sector, such as the Tejas Light Combat Aircraft, INS Vikrant Aircraft Carrier, the Akash Surface to Air Missile, and the BrahMos Supersonic Cruise Missile, from the simplest to the most complicated, including production, designing, and supporting.

Major Indigenous Programs

Aerospace: Tejas LCA, Light Combat Helicopter (LCH), Advanced Light Helicopter (ALH), Dhruv

Naval Platforms: INS Vikrant aircraft carrier, Kalvari-class submarines (Project 75), various destroyers and frigates

Missile Systems: Agni series (I-V), Prithvi, Akash, Nag, Astra, BrahMos

Artillery: Dhanush 155mm gun (81% indigenous content), Advanced Towed Artillery Gun System (ATAGS)

The Export Surge: From Importer to Exporter

Remarkable Export Growth

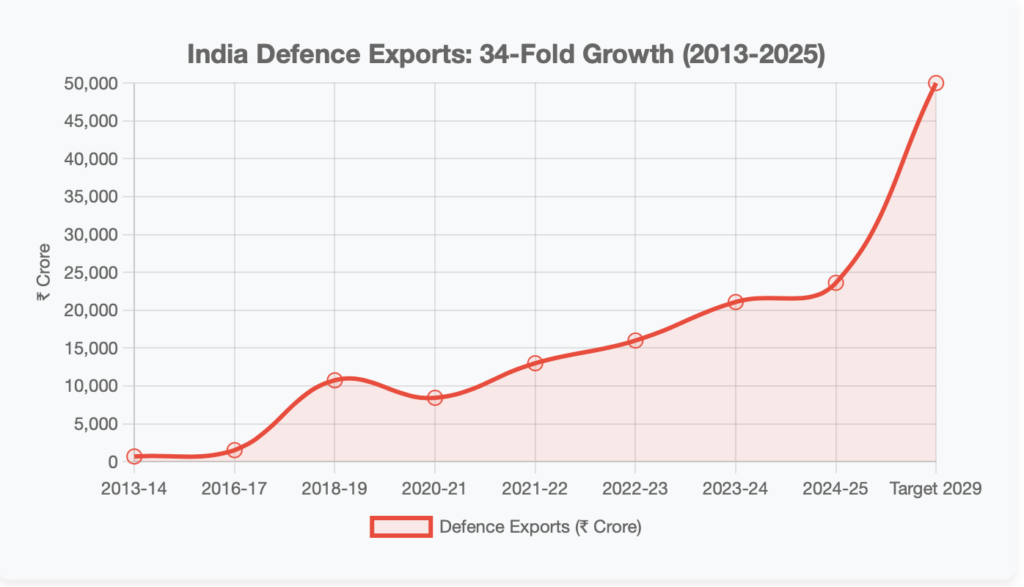

One of the most remarkable changes in India’s defence industry is represented by the huge increase in defence exports. From a mere ₹686 crores in the fiscal year 2013-14, 34 times more exports of ₹23,622 crores were made in the fiscal year 2024-25. The mentioned growth path indicates India’s acceptance of being a reliable defence partner, which has allowed the country to export to more than 100 countries.

At present, the private sector is responsible for the major part, 64.5% (₹15,233 crore) of defence exports, while the public sector units (DPSUs) are holding 35.5% (₹8,389 crore) of the market, the latter having a notable annual growth of 42.85% in their sales. Total exports from 2014-15 to 2023-24 were ₹88,319 crores, which is approximately 21 times the previous decade’s export of ₹4,312 crores only.

| The United States, France, and Armenia, in that order, emerged as the largest buyers of Indian defence articles in the year 2023-24. The remarkable $375 million contract of BrahMos with the Philippines in 2022 highlighted the capabilities of India to market sophisticated arms. |

Complete self-reliance is only achievable through a continuous and lengthy process involving R&D investments, proper procurement channels, participation of the private sector and public funding.

Import Dependency: The Declining Trend

According to SIPRI, India has had the disreputable distinction of being the largest arms importer in the world, responsible for 9.8% of the total global arms imports in 2019-2023. But the trend still shows the positive signs of a decrease. The period of 2015-19 saw a reduction of 9.3% in arms imports as compared to the period of 2020-24, and the net import content has also decreased significantly from 41.81% in 2018-19 to 36% in 2020-21.

There has also been a major change in the countries from which India sources arms imports. The share of imports from Russia came down from 72% in 2010-14 and 55% in 2015-19 to only 36% in 2020-24. This reduction is a testimony to both the development of India’s home-grown military capabilities as well as to the strategic shift towards Western suppliers, which include France, Israel, and the United States. The Indian government has a plan to cut the dependence on arms imports to under 30%, thus getting closer to the country’s 1947 dream of being self-sufficient.

Structural Challenges and Future Outlook

Persistent Challenges

India’s defence modernisation faces several challenges even after the remarkable progress made.

- Budget Constraints: Defence spending at 1.9% of GDP is below the recommended 3% threshold, which limits the scope of modernisation programs.

- Personnel Costs: The defence budget is largely consumed, i.e., 53.4% by pay, allowances, and pensions, thereby cutting down the capital expenditure.

- Technology Gaps: There are still critical dependencies for engines, avionics, sensors, and advanced materials.

- Procurement Delays: Equipment induction is delayed due to complex procedures and multi-year field trials.

- R&D Intensity: Private sector R&D investment is not, compared to global benchmarks, sufficient.

- Global Competition: High-end platforms are dominated by well-established exporters like the USA, Russia, and France.

Strategic Initiatives for 2025 and Beyond

The government has designated 2025-26 as the “Year of Reforms” to accelerate transformation. Key initiatives include:

| iDEX (Innovations for Defence Excellence): The iDEX initiative from 2018 has led to the signing of more than 350 contracts totalling ₹2,300 crore, and a further ₹400 crore will be allocated under the ADITI scheme in 2024-25. Start-ups and MSMEs are partnering with the government to come up with next-generation defence technologies through this program. |

The SRIJAN website, which is the portal for the Self-Reliant Initiatives through the Joint Action program, offers a total of 38,000 items that are to be indigenized and 14,000 that have been indigenized successfully so far. The new defence industrial corridors in Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are turning the regions into magnets for aerospace and defence production, and on top of that, the Defence Testing Infrastructure Scheme (DTIS) is going to create eight new testing facilities.

Conclusion: Toward Strategic Autonomy

India’s defence modernisation taking place over the period 1990-2025 signifies a changing of the guard from reliance to self-sufficiency. It is these very facts that point to the full-fledged transition towards strategic independence: an increase of indigenous procurement from 25% in 2014 to 68-70% in 2024, production growth of 60% since 2019-20, and exports rising by 34 times during the same period. However, complete self-reliance is only achievable through a continuous and lengthy process involving R&D investments, proper procurement channels, participation of the private sector and public funding. With a plan of ₹3 lakh crore in defence production and ₹50,000 crore in exports by 2029-30, India is set not only to become a major player in defence manufacturing but also a quality supplier and technology collaborator for countries seeking quality defence solutions.

The shift of India from being a 1990 import-dependent military to a 2025 self-reliant and export-capable defence industrial ecosystem is a reflection of its growing comprehensive national power. India is at a crossroads in its security strategy as the border issues with China and Pakistan have started to create new security concerns. Accordingly, the upgrading and localisation of the defence sector became not merely economic necessities but also vital components of national independence and strategic autonomy.

| Vision 2030: India is aiming to be in the top five global defence manufacturers and, at the same time, nearly completely self-sufficient in the critical defence technology, and the country would be able to support the Indo-Pacific as a net security provider due to the combination of strong policy measures, the upgrading of industrial capabilities and the continuous development of technological skills. |

Data Sources:

- Ministry of Defence (Government of India),

- DRDO Annual Reports,

- SIPRI Database,

- Union Budget Documents (2020-2026),

- Press Information Bureau,

- Defence Industry Reports

Divyanka Tandon holds an M.Tech in Data Analytics from BITS Pilani. With a strong foundation in technology and data interpretation, her work focuses on geopolitical risk analysis and writing articles that make sense of global and national data, trends, and their underlying causes. Views expressed are the author’s own.