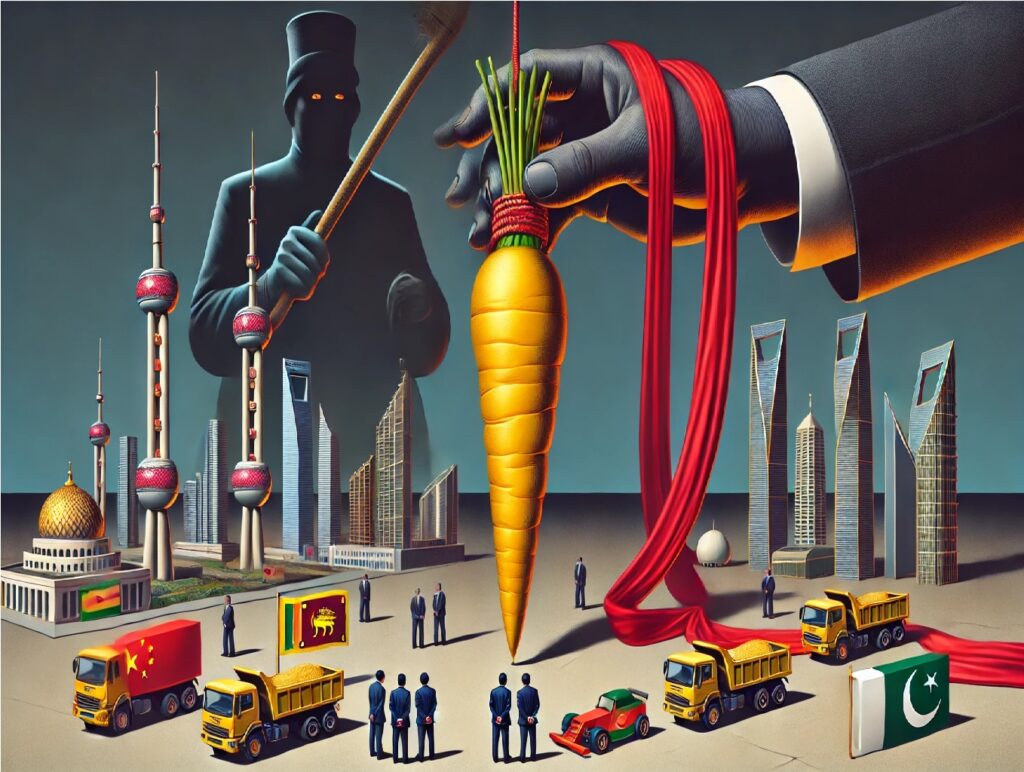

- Neocolonisation is a practice through which big countries tend to have an indirect influence over the smaller countries and experts have argued that the Chinese BRI project is a pretext for its way of neocolonisation.

- More than twenty countries have debts to China that exceed 10% of their GDP.

- The fear of strategic concessions—such as allowing China’s military or logistical access to key locations—remains a topic of debate among regional analysts.

- Countries can bolster their local expertise and infrastructure which allows them to manage and oversee projects effectively.

Chinese Belt and Road initiative has created problems for global financial institutions. Though this has aided infrastructure projects, it has also raised concerns regarding debt sustainability, economic independence, and geopolitical influence. Developing countries, in particular, have become heavily indebted to China, which has created problems ranging from internal politics to geopolitics.

Between 2000 and 2021, Chinese policy and commercial banks provided approximately $57 billion in loans to 19 low- and middle-income countries, primarily for clean energy, infrastructure, and mining initiatives. China’s control over global supply chains for rare earths, lithium, and cobalt—essential minerals for green technologies—has been reinforced through this strategy. However, for borrowers, it has created significant debt problems. More than twenty countries have debts to China that exceed 10% of their GDP. Considering that since 2000, there have been over 150 instances of loan defaults, restructurings, or credit crises, notably, since 2016, the number of countries facing defaults on Chinese loans has more than doubled. As of 2021, Sri Lanka owed approximately $7.4 billion to Chinese lenders, constituting 20 per cent of its public external debt. It is evident that China has played a major role in Sri Lanka’s debt responsibilities.

Modus Operandi of China’s Dept Trap Diplomacy

A prominent example is the Hambantota Port project. Unable to pay the Chinese loan Sri Lanka has decided to hand over the Hambantota port to China for a lease of 99 years. In fact, outside Hambantota, Sri Lanka has struggled to repay loans on other Chinese-financed infrastructure projects, such as highways and power plants. All these factors complicated the country’s broader economic crisis in the past few years, fueled externally by debt burdens and depleted foreign reserves that served to further spotlight the risks of over-reliance on Chinese financing.

Pakistan’s loan to China is heavy. Pakistan’s indebtedness to China reached approximately $30 billion in 2022, which constitutes nearly 30 per cent of its foreign debt. These loans mainly relate to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), an infrastructure project designed to enhance connectivity and expedite economic growth. However, the financial conditions of these deals are controversial.

Agreements with Chinese companies to build power plants included expensive terms, requiring Pakistan to pay China for unused power capacity in U.S. dollars. This has led to massive debts, a devalued Pakistani rupee, and electricity bills surpassing household incomes. The impractical decision-making, driven by an urgent power need but resulting in long-term financial strain, now threatens Pakistan’s economy, impacting households and industries. Efforts to renegotiate the power agreements are in progress, and Pakistan is looking for debt relief and better terms. Pakistan’s growing debt has also forced the country into IMF bailouts quite often because of the unmanageable burden it is carrying between the Chinese debt obligations and general economic stability. Without structural reforms, Pakistan is on the brink of becoming completely dependent on China.

In the Pacific, Vanuatu has been one of the centres of Chinese projects where the latter has created a presidential palace. Critics argue that these projects, often presented as gifts, are sometimes enabled through significant loans, leading to fears about repayment capacity.

Similar concerns have arisen in other Pacific countries, such as Tonga and Fiji, which have taken on substantial Chinese loans. These small island nations, with limited economic resources, may struggle to meet their debt obligations, increasing China’s leverage over their political and economic decisions. The fear of strategic concessions—such as allowing China’s military or logistical access to key locations—remains a topic of debate among regional analysts.

China and Neocolonisation

China’s global lending has also triggered strong debates on debt-trap diplomacy, where nations get themselves into unmanageable debts and lose strategic assets. Although some consider that concern an overblown worry, the Hambantota Port leasing by Sri Lanka and debt-related issues in Africa and Southeast Asia have kept people doubtful. Many countries prefer Chinese loans over those of the West because the latter attaches fewer conditions, although transparency still is a problem.

In Africa, China is the largest creditor for many nations, financing roads, ports, and railways. However, countries like Zambia and Kenya have struggled to meet repayment obligations, leading to concerns about asset seizures and financial dependency. The increasing number of nations in financial distress due to Chinese loans raises broader geopolitical questions about China’s role in the global financial system and its long-term strategic intentions. As more countries begin to struggle with repayments, the danger of economic crises and regional instability escalates. The COVID-19 pandemic and other economic problems have forced countries to seek Chinese loans. Also, institutions like the IMF and World Bank have asked China to work with these countries to restructure their debt. Nonetheless, China’s lending practices have raised more inquiries than answers: what motivated the decision to provide such substantial loans at the outset? What is the real cost of these loans for the countries that are borrowing?

As the world watches, China has begun to reassess its borrowing approaches. They’ve decreased high-risk loans and engaged in debt restructuring talks. It’s a step forward, yet many feel it falls short and is long overdue. Take Sri Lanka as an example. They owe an extraordinary $7.4 billion to Chinese lenders, accounting for nearly 20% of their external public debt. Pakistan and Vanuatu are facing similar difficulties.

Neocolonisation is a practice through which big countries tend to have an indirect influence over the smaller countries and experts have argued that the Chinese BRI project is a pretext for its way of neocolonisation. And this left smaller countries to question how to tackle these problems.

Ways to Combat Neo-colonisation

Countries can bolster their local expertise and infrastructure which allows them to manage and oversee projects effectively. Investment in education, training, and institutional capacity building can also help countries negotiate on favourable terms and oversee projects without excessive foreign intervention. Countries can secure terms that protect their interests through proactive and informed negotiations. This includes setting clear repayment schedules, interest rates, and conditions that do not compromise national sovereignty or economic stability. Countries can also have robust laws in place also ensure the safety of national assets while also keeping foreign investments bound to the stipulated laws of the local economy. The laws also provide insulation from being taken advantage of. Collaboration with neighbouring countries can provide collective bargaining power and shared resources, reducing the risk of individual nations being subjected to neocolonial pressures. Regional alliances can also offer mutual support in managing foreign investments.

References:

- https://www.cfr.org/blog/rise-and-fall-bri

- https://www.scirp.org/journal/paperinformation?paperid=110152

- https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/08/debunking-myth-debt-trap-diplomacy/4-sri-lanka-and-bri

- https://www.chathamhouse.org/2020/03/chinese-investment-and-bri-sri-lanka-0/2-economy

- https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/the-bri-in-melanesia

Aayush Pal is a freelance writer on contemporary geopolitical developments. The views expressed in his work are entirely his own.