The Matsu Islands of Taiwan is a relatively small archipelago with a population of 14,000. Relying on fishing and tourism as their primary sources of income, they lead a peaceful life, enjoying all the modern joys of life while occasionally greeting tourists from across the world to experience this secluded haven. However, in April last year, the residents of Matsu Island found themselves unable to watch videos, make calls, or provide internet to their guests due to something ominous. Two undersea cables providing internet access to the Matsu Islands had been cut.

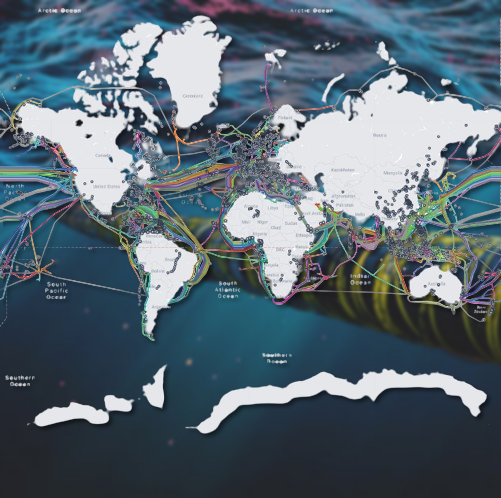

You see, 95% of the world’s internet, contrary to popular belief, is supplied by undersea cables. These cables stretch thousands of kilometres, linking the globe in an attempt to provide universal internet access to everybody, irrespective of their location. As wide as a garden hose, these undersea cables are layered with different coatings of copper, tar, and armour-plating to deal with multiple threats like shark attacks, trawler mishaps, or free-roaming ship anchors, all for the sake of ensuring that you are provided unrestricted internet access to watch a compilation of kittens.

The residents of the Matsu Islands must find this rather normal at this point, as they endure disruptions like these periodically. Disconnected around 27 times over the past five years, there’s one common element: the occurrence of a Chinese trawler or a repair ship looming in the distance. A recent warning issued by the U.S. State Department last month warns all Big Tech companies such as Meta, Amazon, and Google, which lay claim to over 100,000 km of sea cables across the globe, regarding the prevalent threat of certain ship repair corporations unusually looming around waters where their cables are present. In particular, the State Department singles out S.B. Submarine Systems, a repair company owned by the Chinese state, as a major perpetrator of global interest.

In April last year, the residents of Matsu Island found themselves unable to watch videos, make calls, or provide internet to their guests due to something ominous.

This new front of throwing down military might seem to be gaining headway over the past few years. What began as a collective effort to connect the world and provide them with the potential opportunities of the internet has now devolved into an avenue of trying to crush the possibility of a multipolar world. To provide you with a clearer context of what makes governments invested in these sea cables, the interest is twofold. First is the sheer richness of data variety. Ranging from simple commercial data such as shopping purchases to bank transactions, the data carried by these sea cables also passes on military secrets and actions all through the same cable.

One can thus understand how important these sea cables become in the broader game played between global powers. And there’s no small money involved in this. Each cable project costs around $300-400 million and can span about 10,000+ km. The world’s largest underwater sea cable, the 2Africa cable system, is 45,000 km long. The Earth’s circumference is 40,000 km. Yes, that’s the distance we’re talking about.

It’s not just China that finds itself interested in occasionally sabotaging these sea cables. As Bloomberg highlighted in their excellent piece, there was a rather suspicious disruption in network services off the coast of Norway with a small archipelago, Svalbard. Svalbard, around 7 months ago, was completely disconnected from the mainland coast for the span of a few hours. The catch? Svalbard consists of a significantly important satellite installation that relayed geospatial data back to NATO and its allies. And surprisingly, as the report points out, one particular Russian trawler circled the two cables connecting Svalbard and Norway 130 times! If this does not seem fishy, I don’t know what does! (My apologies for the pun).

Russia seems to be doing this at a frequency that is unconventional compared to the past few decades. While fishing has been an area of cooperation between Norway and Russia, two suspicious undersea cable damages linked to Russian vessels now seem to be opening a can of worms that might be unsavoury for any party.

The undersea cables are layered with different coatings of copper, tar, and armour-plating to deal with multiple threats like shark attacks, trawler mishaps, or free-roaming ship anchors, all for the sake of ensuring that you are provided unrestricted internet access to watch a compilation of kittens.

Let’s now shift our sights towards the Middle East. Fraught with conflict, the Middle East now sees different rebel groups interspersed in Yemen (the Houthis), Jordan (the Hezbollah), and Hamas, all directing some of their anger towards Israel and her allies. Let’s not direct ourselves to the conflict, as that plays second fiddle to the significant side effect reverberating across the Red Sea. Carrying about 90% of internet traffic between Europe and Asia, the Red Sea cable network underground has now begun to become a vulnerable target for the Houthis to aim at.

The difficulty of pinning the blame on any party lies in the nuances of maritime law. While the maintenance and repair of undersea cables in regional waters are ascribed to the nation whose economic purview the cables come under, most damage to sea cables is undertaken in international waters. In such cases, the law simply mandates the perpetrator be punished based on the flag of the ship he’s on. Ironically, the law voids itself if the perpetrator is the state.

As we saw earlier this year, the sinking of the United Kingdom ship Rubymar resulted in a catastrophic oil spill. A consequence of this sinking was its haywire anchor damaging four underwater sea cables, causing damage to an assortment of cables worth $3.5 billion. This unintended complication has given the Houthis food for thought, as seen in some of their Telegram groups, circulating maps of sea cables present in the Red Sea. While they do lack the infrastructure required for such damage, they seem to have taken a step in that direction.

It might be easy to continue blaming the sabotage of these cables on our standard actors – Russia, China, and unwanted rebel groups. However, the battle of underwater sea cables also ensues on the surface. In this case, nobody can beat the United States in terms of sabotage. Take the case of the SeaMeWe-6, a 16,000 km sea cable stretching from Singapore to France, which connects India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Djibouti on the way. This $600 million project was won by SubCom, a US-based cable company that actively utilized United States assistance in winning this contract by forcefully pushing out its fellow bidder, a Chinese corporation called HMN Tech.

Deploying embassies across all participating countries, the SeaMeWe-6 contract was won by a deliberate plan hatched by the United States to coerce all parties involved by first threatening sanctions on HMN Tech. Further, the United States utilized the power of embassies and the fear of surveillance by China as a threat to the participating nations’ sovereignty as a means to win the contract. This seems rather hypocritical after Edward Snowden highlighted the nonchalant nature of the United States when it came to spying on its citizens. And a pleasant surprise? India too was involved in this project through the Bharati Airtel group.

With a weak legal framework and the sheer vastness of the oceans, nailing down a perpetrator is next to impossible. The difficulty of pinning the blame on any party lies in the nuances of maritime law.

I won’t deny the significant negatives associated with China winning the contract. However, the attempt of media across the world to highlight only Russia and China as those engaged in the game of sabotage is rather idiotic. Anybody knows it always takes two to play a game. The only difference is that the United States uses the diplomatic and monetary route to win hearts, while the Chinese and the Russians allegedly rely on guerilla tactics (the word “allegedly” is doing the heavy lifting here).

With a weak legal framework and the sheer vastness of the oceans, nailing down a perpetrator is next to impossible. However, it is now evident that new fronts of war are opening. And it seems that these fronts are a consequence of us realizing the value of information. The ’60s saw the onslaught of the Cold War; we now find ourselves in an era of the Info War, where each party strives to control the narrative through access to data, rather than engaging in blood and steel.

(Divith Narendra is a student of data science, economics, and business with a passion for integrating data and statistics. He writes extensively on industry trends and geopolitics. His works were featured at the G20 and published by Cambridge Union Press. Views expressed are the author’s own)

References:

- bloomberg.com/features/2024-undersea-cable-sabotage-russia-norway

- https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/undersea-chokepoints-the-red-sea-cable-disruptions

- https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/african-internet-outage-was-caused-by-subsea-cable-break-mainone-says-2024-03-15/

- https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/us-china-tech-cables/

- https://www.wsj.com/politics/national-security/china-internet-cables-repair-ships-93fd6320

Unless governments of the world take note of the geopolitics of undersea cable, predatory powers like China will try to use it to harass or blackmail smaller countries.

Important intervention hardly covered in the media. This is a war waiting to happen and countries must guard their interests with hegemonic forces on the prowl. I guess Musk’s Star Link kind of solution is the way forward to avoid any untoward takeover by nefarious entities.