- The New Start treaty, signed in 2010, limits the number of long-range nuclear warheads that the US and Russia can possess.

- The New START aims to prevent another arms race from unfolding, and reduces the risk of an accidental escalation.

- Given unrealistic demands from the Trump administration to extend the New START treaty, Moscow and Washington were forced to wait until the inauguration of Biden administration

- India hopes that the New START triggers a debate on complete withdrawal of nuclear weapons while restricting it to production of clean energy.

India on Thursday said that it welcomes the ‘New START’ treaty between the US and Russia for five years, saying it will help in addressing international non-proliferation and disarmament issues. “India welcomes the agreement between the US and Russia to extend the treaty on measures for the further reduction and limitation of strategic offensive arms (New START Treaty) by five years,” the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) said in a statement.

“We hope that this will promote dialogue and cooperation to help address international non-proliferation and disarmament issues,” the MEA said.

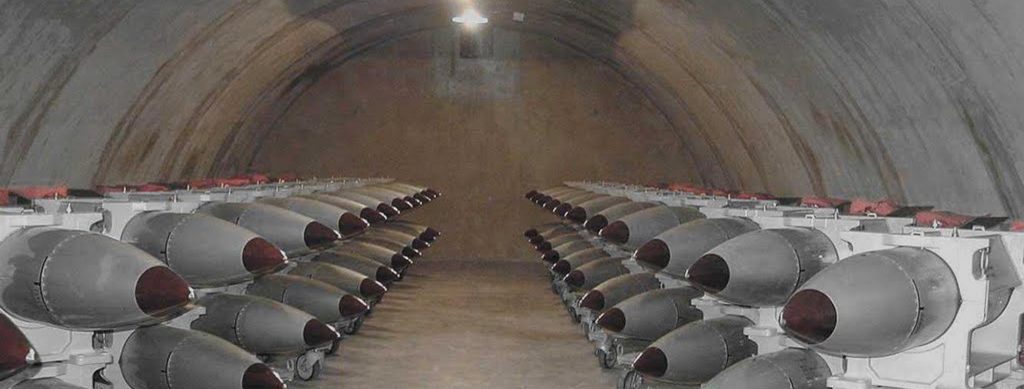

The New Start treaty, signed in 2010 and came into force on February 5, 2011, limits the number of long-range nuclear warheads that each side can possess. New START caps to 1,550 the number of nuclear warheads that can be deployed by Moscow and Washington, which control the world’s largest nuclear arsenals. The agreement was due to expire on February 5.

This is the last major pact of its kind between the two countries after the US under the Trump administration pulled out of a separate nuclear arms control agreement with Russia called the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) in 2019. The New START aims to prevent another arms race from unfolding, and reduces the risk of an accidental escalation. Its extension should have been an obvious step and routine affair that passed without any fanfare, amid talks on the next U.S.–Russian arms control agreement.

Instead, the Trump administration used the New START to try to extract concessions on other issues from Russia. This tactic failed, since the conditions laid down by Trump were unrealistic. Moscow and Washington were forced to wait until the inauguration of Biden, when there were only about two weeks left to extend the treaty.

Announcing the extension of the treaty, Secretary Antony Blinken said that “President Biden pledged to keep the American people safe from nuclear threats by restoring U.S. leadership on arms control and nonproliferation.”

Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the legislation extending the treaty last Friday. The United States and Russian have agreed to extend the treaty through February 4, 2026.

Agreed Limits on warheads

Both the United States and the Russian Federation met the central limits of the New START Treaty by February 5, 2018, and have stayed at or below them ever since. Those limits are:

- 700 deployed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), deployed submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and deployed heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments;

- 1,550 nuclear warheads on deployed ICBMs, deployed SLBMs, and deployed heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments (each such heavy bomber is counted as one warhead toward this limit);

- 800 deployed and non-deployed ICBM launchers, SLBM launchers, and heavy bombers equipped for nuclear armaments.

New START limits all Russian deployed intercontinental-range nuclear weapons, including every Russian nuclear warhead that is loaded onto an intercontinental-range ballistic missile that can reach the United States in approximately 30 minutes. It also limits the deployed Avangard and the under development Sarmat, the two most operationally available of the Russian Federation’s new long-range nuclear weapons that can reach the United States.

Extending New START ensures that the US will have verifiable limits on the mainstay of Russian nuclear weapons that can reach the U.S. homeland for the next five years.

As of the most recent data exchange on September 1, 2020, the Russian Federation declared 1,447 deployed strategic warheads. The Russian Federation has the capacity to deploy many more than 1,550 warheads on its modernized ICBMs and SLBMs, as well as heavy bombers, but is constrained from doing so by New START.

What does the New START NOT cover?

With the collapse of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty and Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, restrictions on anti-missile defense systems and short- and intermediate-range missiles disappeared. The extension did not cover this aspect. Further, conventional weapons in space and nonstrategic nuclear weapons have never been regulated by international treaties including the New START.

The United States and Russia have never agreed on the above issues as each wish to maintain their seeming superiority in the area. Further, both the powers do not wish to subject their conventional missile arsenals to any treaty in the interest of their national security. While reports suggest that the US has made a quantum leap in terms of missile defense solutions, Moscow has been talking of “strategic equalization” with the United States. In such a scenario any treaty on conventional weapons can hardly be expected.

In case such a treaty had to take shape in the interest of the entire world, talks need to begin now. The extended New START will expire in 2026, but a new US President in 2024 could well play the spoilsport again, similar to the way Trump approached the international treaties.

Why has India welcomed the New START?

India is not a member of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) or the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), but is a state party to the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT). India embarked on a nuclear energy program in 1948 and a nuclear explosives program in 1964. This culminated in India’s successful nuclear tests in May 1974. In May 1998, India tested five nuclear weapons and formally declared itself a nuclear weapons state.

According to 2020 estimates, the Indian arsenal comprises approximately 150 nuclear warheads, one operational Arihant-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) and fighter aircrafts capable of carrying nuclear missiles.

However, India is way behind the top five nuclear powers including China which poses a major threat to its security and integrity. China exploded its first weapon in 1964 and the NPT came into effect in 1970. Under its terms, China became recognised as one of the world’s five ‘weapon states’, and India was excluded from such status.

Hence India was left with the choice of remaining outside the NPT or relinquishing any possibility of maintaining even a minimal nuclear deterrent. In the light of strategic challenges it faces from both China and Pakistan, India chose a nuclear deterrent. Instead of forcing the top nuclear weapon states to relinquish the nuclear weapons altogether, international efforts have been working to target or penalise countries like India in order to build a stronger non-proliferation regime. It is this duplicitous approach that India has opposed for decades.

Further in 1992, in an effort to expand participation of countries in the NPT, the informal ‘club’ of nations called the Nuclear Suppliers Group decided to prohibit all nuclear commerce with nations that have not agreed to full-scope safeguards. This precondition effectively required countries to join the NPT as non-weapon-states if they were to participate in nuclear commerce. Practically, this left India as a pariah in the world of nuclear commerce.

India has said that it is bound by its ethos of self-reliance as it continued its long-held policy of maintaining a small nuclear deterrent while pursuing peaceful nuclear power on an ever-larger scale. In parallel India has also chosen to sign commercial nuclear deals with several countries to participate in the nuclear commerce, these include US, France, Russia, Japan and others. In March 2006 India and the USA signed an agreement designed to put India on the same basis as China in relation to international trade in nuclear technology and materials.

India is not yet a member of the NSG and its attempts at inclusion have been thwarted by China. India hopes that in lieu of the NSG advantage, the US, Russia, Japan and the European members of the NSG recognise India’s growing needs for clean energy and would be lenient towards it given its blemishless track record. India hopes that the New START triggers a debate on complete withdrawal of nuclear weapons while restricting it to production of clean energy.

The world must differentiate between nuclear weapons and clean nuclear energy. India has shown its will to foster nuclear technology for energy purposes. India is ready to fulfill its civil nuclear potential and assert its status as a responsible nuclear state. It is time for the major nuclear powers to disband their nuclear arsenal and commit to use of nuclear energy only for civilian purposes. It is in this respect that India hopes that the extension of the New START treaty between US and Russia should trigger a debate on a world without nuclear weapons and use of nuclear technology only for peaceful purposes.