- The battle for control of the Caspian Basin’s enormous oil resources, which includes billions of dollars and significant strategic influence, is a narrative of political intrigue, intense commercial competition, geostrategic rivalries, ethnic feuding, and elusive independence.

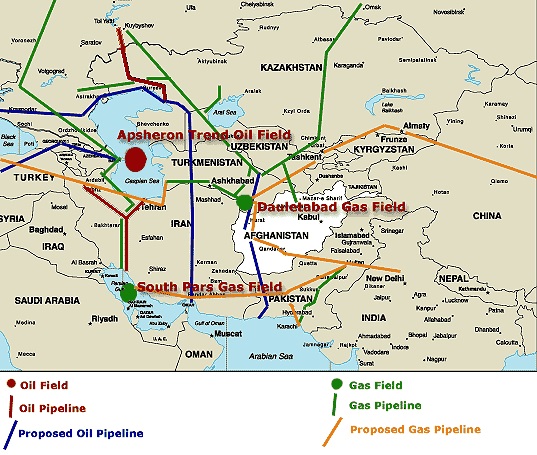

- The US is in favour of building an east-west energy transit corridor that will bring Caspian oil to global markets through a network of numerous pipelines, avoiding Iran’s possible chokepoint and lowering reliance on Russian oil pipelines.

- China uses its policies in Central Asia to manage Russia’s concerns by demonstrating that its economic objectives do not pose a threat to its political-military interests in the Russian Far East and other regions.

Conceptualisation of New Great Game

The phrase “New Great Game” was coined in the late 1990s to characterize a resurgence of geopolitical interest in the context of Central Asia because of the region’s abundant mineral resources. The original term “Great Game” alludes to the political and diplomatic struggle between the Soviet and British empires in the 19th century for influence and territory among the states of Central Asia. With the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the phrase “Great Game” itself began to be used more frequently.

Alexander Cooley advocated for the study of the “New Great Power Contest in Central Asia”. He introduces the historical “great game of the 19th century” and draws parallels between its dynamics and the ongoing competition between the United States and China for supremacy in Central Asia. The goals of these two superpowers in the region are different: China wants to stabilize its province of Xinjiang through security cooperation, regional economic development, and access to Central Asian energy; the United States wants bases and transit routes to support its operations in Afghanistan. Nevertheless, the governments of Central Asia are also at the forefront of this new great game. They have taken advantage of the increased attention and competition from outside sources to fortify their domestic power and extract economic benefits. Their ability to deftly play off one another’s foreign powers offers valuable insights into the post-Western, multipolar world’s developing political dynamics and ensures access to vital raw materials needed for strategically important industries like clean energy technology, medical appliances, aerospace, and defence.

This article aims to understand how the big powers are locked in a murky geopolitical game in Central Asia. Western analysts predict that the Caspian Sea region will become the Persian Gulf of this century due to its abundant natural gas and oil reserves, which are still mostly unexplored. The goal of the resurrected game is to make friends with the current leaders of the former Soviet republics that control the oil to allay Russian concerns and create safe routes for pipelines to access international markets. The expected outcome is to problematize the strategies followed by these great powers.

The phrase “New Great Game” was coined in the late 1990s to characterize a resurgence of geopolitical interest in the context of Central Asia because of the region’s abundant mineral resources.

Perspectives and Arguments on Great Power Rivalry

Journalist Lutz Kleveman, author of “The New Great Game: Blood and Oil in Central Asia in 2004”, connected the expression to the discovery of the area’s mineral wealth. Another journalist, Eric Walberg, makes the argument that “access to the region’s mineral resources and oil pipeline routes is still a significant factor, even though the United States direct military involvement in the region was part of the War on Terror rather than an indirect Western governmental interest in the mineral wealth. Pipelines carrying energy to China’s east coast are part of the interest in oil and gas. A perspective on the New Great Game suggests a transition from geopolitical to geoeconomic rivalry”.

The term “Great Game” has been criticized by other authors. Strategic analyst Ajay Patnaik claims that the term “New Great Game” is misleading because, unlike in the past, when only two empires were concentrating on the region, there are now numerous regional and global powers involved due to the rise of economic giants namely China and the US. States in Central Asia now have a wider range of economic, political as well as security ties. David Gosset of “CEIBS Shanghai” mentions that “The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), which was established in the year 2001, is giving a larger degree of independence of decision making to the Central Asia’s actors. However, the China factor essentially adds a degree of predictability.”

Furthermore, to counterbalance the economic and political interests of stronger nations, the Central Asian states have adopted a “Multivector Foreign Policy Strategy”. The Multivector Foreign Policy is characterized by a pragmatic, non-ideological approach. This gave Central Asian leaders more leeway in advancing their nation’s political, security, and economic interests when interacting with regional and international powers. These nations openly depended on Russia to maintain connectivity with the outside world. As a result, it tried to use its vast repository of natural resource base to diversify its incoming investments and advance this vital industry. This is illustrated by the reality that Central Asian states have formed strong alliances with China, the United States, Turkey, Iran, as well as India, among other regional and extra-regional powers.

However, due to deliberate administration shifts with respect to China and the West, this approach has had varying degrees of success. They believe China has the ability to balance Russia. Nonetheless, since 2001, China and Russia have maintained a strategic alliance. As Ajay Patnaik puts it, “China has advanced carefully in the region, using the SCO as the main regional mechanism, but never challenging Russian interests in Central Asia.” Paul Stronski and Nicole Ng stated in a 2018 Carnegie Endowment study “that China has not fundamentally challenged any Russian interests in Central Asia. They proposed that regional stability in Central Asia could be of interest to China, Russia, and the West simultaneously. China uses its policies in Central Asia to manage Russia’s concerns. China appeases Russia by demonstrating that its economic objectives do not pose a threat to its political-military interests in the Russian Far East and other regions outside of Central Asia, as well as by allaying its demographic concerns regarding Chinese immigration”.

Central Asian states have adopted a “Multivector Foreign Policy Strategy” giving them more leeway in advancing their political, security, and economic interests when interacting with regional and international powers.

During the initial withdrawal of the American forces from Afghanistan in 2014, historian James Reardon-Anderson declared, “A trend of a new Great Game in Central Asia is very much visible. It would be very important for the regions in Western Pacific and East Asian waters.” One could note that “China, Pakistan, Russia, as well as Iran, could come together in the next chapter of the Great Game” or that “Beijing, Tehran, Islamabad as well as Moscow would look to advance their own interests in the new geopolitical order“. In the future, these would be the strong contenders against the United States.

As part of a national energy policy that advocates for the expansion of oil production outside of the Arab Gulf, the United States initially supported the development of Caspian oil. After some time, the U.S. policy changed to include three primary regional policy objectives:

- Support for the newly independent states (NIS) of the Caspian in terms of their independence and sovereignty.

- Expanding trade prospects for American businesses and the US itself.

- Establishing pipelines or other economic ties between these states to reduce regional conflicts and benefit neighbouring countries.

To achieve these goals, the US is in favour of building an east-west energy transit corridor that will bring Caspian oil to global markets through a network of numerous pipelines, avoiding Iran’s possible chokepoint and lowering reliance on Russian oil pipelines. This network includes the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), which links the massive Tengiz oilfield in western Kazakhstan to the Russian port of Novorossiysk on the Black Sea; the new early-oil pipelines from Baku to Supsa and Novorissiysk; the proposed Baku-Tbilisi Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline, which would transport oil from Azerbaijan to the Turkish Mediterranean port of Ceyhan; and a trans-Caspian gas pipeline that would run from Turkmenistan to Turkey.

Kazakhstan is the undisputed winner among nations, with up to 75% of all Caspian reserves currently thought to be in its possession.

Future of the Caspian Basin’s Reserves

In conclusion, the Great Game is essentially a contest between the owners of the Caspian oil reserves and the control of the pipelines that transport the oil to international markets. The battle for control of the Caspian Basin’s enormous oil resources, which includes billions of dollars and significant strategic influence, is a narrative of political intrigue, intense commercial competition, geostrategic rivalries, ethnic feuding, and elusive independence. The game is too early to call it over. However, following years of ambiguous wrangling, the Great Game of the twenty-first century is beginning to produce distinct corporate and national winners. Companies like British Petroleum, ENI of Italy, Chinese National Petroleum Corporation, and—most importantly—ChevronTexaco of the United States seem to be vying for the majority of the region’s reserves and vital pipeline routes. The nation in the strongest negotiating position ultimately emerges victorious from the Great Caspian Game. Kazakhstan is the undisputed winner among nations, with up to 75% of all Caspian reserves currently thought to be in its possession.

References:

- Baylis, J., Wirtz, J., Cohen, E., Gray, C.S. (2003). Strategy in the Contemporary World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Chen, Xiangming; Fazilov, Fakhmiddin.(2018). Re-centering Central Asia: China’s “New Great Game” in the old Eurasian Heartland. Palgrave Communications. 4 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0125-5. ISSN 2055-1045. S2CID 49311952.

- Cooley, Alexander. (2012). Great Games, Local Rules the new great power contest in Central Asia. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Liddell Hart, B.H. (1967). Strategy: the Indirect Approach. London: Faber & Faber.

- Meyer, Karl E.; Brysac, Shareen Blair. (2009). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-3678-2.

- Patnaik, Ajay. (2016). Central Asia: Geopolitics, Security and Stability. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 28–31. ISBN 9781317266402.

- Roy, O. (2000). The New Central Asia: the Creation of Nations. London & NY: I. B. Tauris Publishers.

- Stronski, Paul; Ng, Nicole (2018). Cooperation and Competition: Russia and China in Central Asia, the Russian Far East, and the Arctic. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Dr. Lakshmi Karlekar is an Assistant Professor at the School of Humanities – Political Science and International Relations, Ramaiah College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Bengaluru. She holds a PhD in International Studies and has consistently ranked at the top during her academic journey at the Department of International Relations, Political Science, and History at CHRIST (Deemed to be) University, Bengaluru. Views expressed are the author’s own.