- Afghanistan’s geostrategic importance stems from its unique geographical location, serving as a critical junction for regional powers, including China, Russia, India, and Iran.

- For Beijing and Islamabad, CPEC is more than just an infrastructure project; it’s a geopolitical tool aimed at consolidating influence in South Asia and resisting India’s regional ambitions.

- India views CPEC and Gwadar as part of China’s ‘String of Pearls’ strategy, which aims to encircle India and threaten its maritime balance in the Arabian Sea.

- India’s next steps must strike a strategic balance between expressing moral opposition to PoK while working sensibly with Kabul.

The Beijing Breakthrough

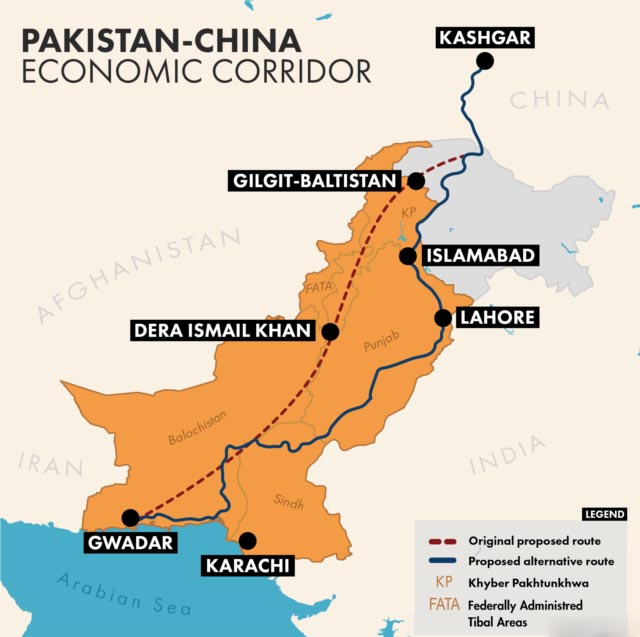

On May 21, 2025, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi held a “informal” trilateral meeting in Beijing with Pakistan’s Ishaq Dar and Afghanistan’s Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi. The ministers unanimously decided to extend the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a key component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), into Afghanistan.[1] They also pledged to intensify trilateral diplomatic cooperation and hold the next Foreign Minister’s Dialogue in Kabul at the earliest opportunity. This signals a significant activation of geoeconomic goals across several borders, incorporating Afghanistan into a corridor that formerly directly connected Xinjiang to Pakistan’s Gwadar port, but has far-reaching geopolitical implications for South and Central Asia.

Afghanistan: What It Gives, What It Gains

Afghanistan’s geostrategic importance stems from its unique geographical location, serving as a critical junction for regional powers, including China, Russia, India, and Iran.[2] Historically, the region has been characterised by external influences and internal strife, making it a focal point for geopolitical competition, often referred to as the “Great Game” during the 19th century, when British and Russian empires vied for control over Central Asia.[3] With the recent shift in power dynamics following the US withdrawal from Afghanistan in August 2021, China has sought to engage with the Taliban government.

The trilateral agreement envisions major infrastructure development, ranging from highways (particularly Peshawar-Kabul) and rail connections to logistical and trade facilitation centres within Afghan territory.[4] Afghanistan is rich in minerals, particularly rare earth elements, and its energy industry would benefit from planned pipeline, power grid, and renewable energy expansions channelled through CPEC-linked Special Economic Zones (SEZs). Improved connection may allow Afghan goods such as dried fruits, carpets, and minerals to reach global ports directly via Gwadar. This generates jobs, supports businesses, and may assist in lessening insurgency by providing measurable economic advantages.[5] In exchange, Afghanistan agrees to safeguard its portion of the corridor, facilitating Chinese-Pakistani investment flows and ensuring peace along critical routes, answering Beijing’s fears about militancy damaging its economic footprint. The historical context of Afghanistan as a landlocked nation situated at the crossroads of multiple key regions underscores its potential role in facilitating connectivity and economic growth through the CPEC, provided that stability can be achieved amid ongoing geopolitical rivalries and security challenges.[6]

The trilateral agreement envisions major infrastructure development, ranging from highways (particularly Peshawar-Kabul) and rail connections to logistical and trade facilitation centres within Afghan territory.

CPEC as a Strategic Lever

For Beijing and Islamabad, CPEC is more than just an infrastructure project; it’s a geopolitical tool aimed at consolidating influence in South Asia and resisting India’s regional ambitions. The corridor’s extension into Afghanistan must be viewed as more than just an economic outreach; it is also a purposeful endeavour to alter regional alignments. Strategically, the expansion of Gwadar Port and its integration with China’s marine strategy—also known as the “String of Pearls”—serves to construct a network of Chinese-friendly ports throughout the Indian Ocean.[7]

India sees this as an encirclement strategy aimed at eroding its maritime dominance and exposing important naval bases to attack, particularly along the western shore. The development of CPEC northward into Afghanistan provides China and Pakistan with direct overland access to Central Asia and maybe Europe, bypassing India. This undermines India’s regional connectivity ambitions, such as Chabahar Port and INSTC, and limits its influence in Afghanistan, where India has previously invested in capacity building, education, and infrastructure.[8]

India’s Calculus: From Alarm to Educated Engagement

India continues to oppose the CPEC because it passes through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK), which it considers to be its sovereign territory. India has always resisted CPEC on these grounds, claiming that participants violate Indian sovereignty. Furthermore, India views CPEC and Gwadar as part of China’s “String of Pearls” strategy, which aims to encircle India and threaten its maritime balance in the Arabian Sea.

Simultaneously, India has intensified ties with Afghanistan. On May 15, 2025, External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar conducted a historic ministerial-level call with Acting FM Muttaqi, the first such interaction since 1999. During the call, he “deeply appreciated” Kabul’s denunciation of the Pahalgam terror assault.[9] Delhi also approved the entry of Afghan trucks carrying dried fruits across Attari–Wagah as a “special gesture,” highlighting operational support amid tensions with Islamabad. [10] Further, India has gradually authorised Taliban-appointed representatives to Afghan diplomatic posts in Mumbai and Hyderabad since late 2024, being cautious but proactive.[11] This signals a calibrated, development‑oriented engagement that permits India to retain influence in Kabul without formally endorsing the Taliban or CPEC.

Whether the corridor breeds commerce or conflict will depend less on concrete and more on consensus, an elusive commodity in Afghanistan’s turbulent polity.

Strategic Alternatives: Chabahar, INSTC, IMEC

To counter the expanding footprint of CPEC, India has been actively investing in alternative connectivity corridors that bypass Pakistan and reduce strategic vulnerability. One of the key pillars of this strategy is the Chabahar Port in Iran, which has been operational since 2016. This port offers India direct access to Afghanistan and Central Asia, avoiding Pakistani territory altogether. Recent statements by Taliban officials expressing interest in Chabahar suggest that even Afghanistan may be considering alternatives to the CPEC framework. This is a diplomatic win for India, as it reinforces its relevance in Afghan trade and transit logistics without having to engage with the China-Pakistan alliance on their terms.[12]

Another important initiative is the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a multimodal project that connects India to Central Asia and Europe via Iran, the Caspian Sea, and Russia. This corridor provides strategic depth and a possible alternative to CPEC, especially when combined with Indian investments in Central Asian republics and Eurasian markets.[13]

India is also exploring long-term participation in the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC), which was launched on the sidelines of the G20 Summit in 2023. This transcontinental corridor is designed to improve commercial connectivity and supply chain resilience between India, the Gulf, and Europe. Once operational, IMEC could provide a strategic alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, bolstering India’s position as a crucial node in global trade networks.[14]

Despite its principled objection to the PoK transit, India is unlikely to ignore the CPEC’s Afghan thrust, especially if it stabilises the Afghan economy. New Delhi may choose calibrated engagement in select non-PoK infrastructure areas, including energy or urban development projects, while maintaining its emphasis on sovereignty concerns.

Dynamics Ahead: Fragile Confluence Amid Great Power Play

The Afghan portion of the CPEC has the potential to boost job creation and stability. However, success is dependent on the Taliban regime’s capacity to handle militant challenges, particularly the TTP, which Pakistan and China see as an existential threat to the corridor and its workers.[15] While Islamabad has welcomed India’s diplomatic overtures to Kabul—as long as they do not jeopardise Pakistani interests—it is suspicious of India’s excessive engagement in Afghanistan, particularly in the resource and infrastructure sectors.

Beijing’s involvement as convenor and mediator serves two goals: extending BRI connectivity and projecting China as the stabilising factor in South Asia, a narrative Beijing supports through programs such as the International Organisation for Mediation.

Conclusion: New Chapter in South Asian Order

The CPEC’s attempt to encircle Afghanistan marks a geopolitical turning point. For Islamabad and Beijing, it provides connected development and regional control. It has the potential to open up new growth opportunities for Kabul if aspirational goals are translated into tangible security and governance.

India’s next steps must strike a strategic balance between expressing moral opposition to PoK while working sensibly with Kabul, expanding regional infrastructural alternatives, and safeguarding its economic reach into Afghanistan without compromising sovereignty.

As of mid-June 2025, regional dynamics are still in flux, with India’s engagement with Taliban-era Afghanistan and the ongoing CPEC project representing a realignment in South Asian statecraft. In the next months, India’s balance of strategic prudence, assertive diplomacy, and economic integration will affect regional politics and prosperity.

References:

- [1] China-Pakistan economic corridor to expand into Afghanistan: Why it matters for India

- [2] Unlocking Afghanistan’s connectivity potential – Opportunities for the EU?

- [3] China’s New Engagement with Afghanistan after the Withdrawal

- [4] Afghanistan joins CPEC amid strengthening India-Kabul ties

- [5] China and Pakistan agree to expand the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor to Afghanistan

- [6]A historical timeline of Afghanistan

- [7] Pakistan, Afghanistan move towards ‘restoring ties’ in talks with China

- [8] China-Pak economic corridor to extend to Afghanistan: Why this is a new headache for India

- [9] EAM thanks Taliban for Pahalgam solidarity in 1st political

- [10] Decoding India’s Outreach to the Taliban

- [11]India Steps Up Engagement with the Taliban Regime

- [12] Taliban’s Chabahar bet signals shift from Islamabad to New Delhi

- [13] The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC): India’s Grand Plan for Northern Connectivity

- [14] What is India-Middle East-Europe Corridor and how will it benefit India?

- [15] As Afghanistan and Pakistan mend ties, China could be the real winner

Pranav S is a Project Assistant at the Energy Department, Government of Karnataka with an MA in Public Policy. Views expressed are the author’s own.