- The legal structure of the Non-Proliferation Treaty aims to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons, promote disarmament and, with exceptions, help spread peaceful nuclear cooperation.

- The Non-Proliferation Treaty is one of the most widely ratified arms control treaties in the world, with 191 states parties since it entered into force in 1970.

- Despite its successes, the non-proliferation treaty is confronted by legal as well as geopolitical challenges that undermine its legitimacy.

- The Non-Proliferation Treaty has its flaws, but is still “the best legal bulwark we have against nuclear war”, a thin bulwark indeed, but better than nothing in this unpredictable era.

Introduction

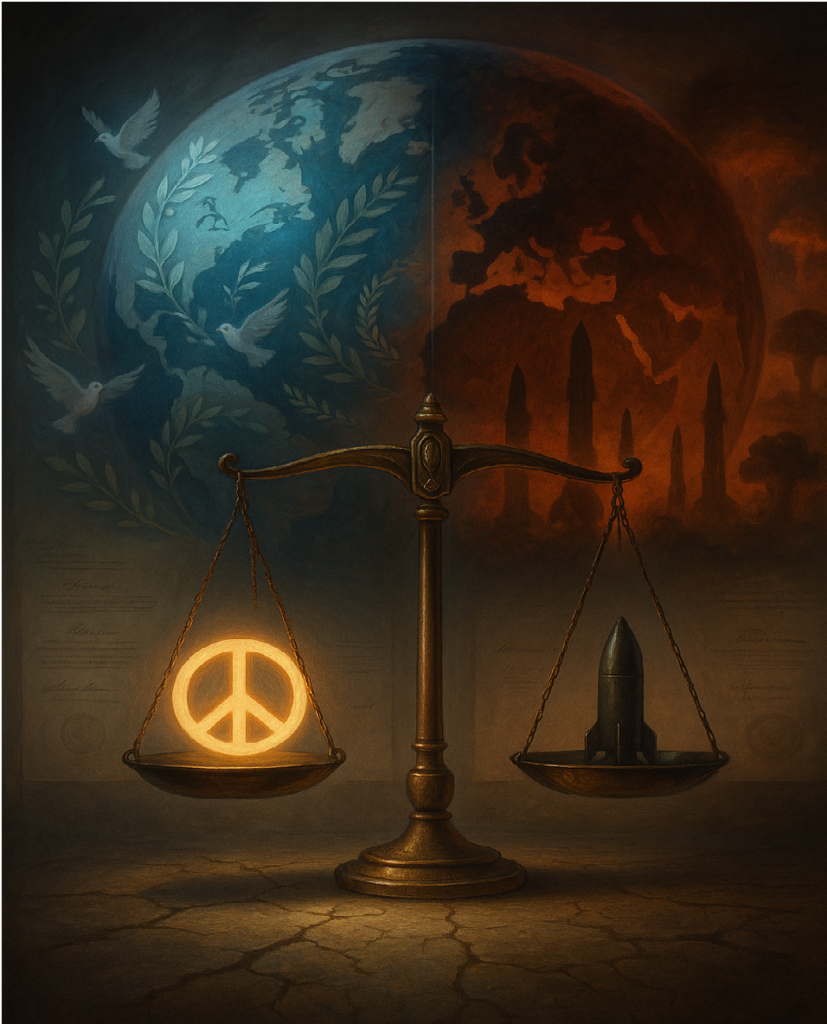

Nuclear technology has come to represent both remarkable power and life-threatening crisis, and in the wake of its world-changing introduction to the world, humanity has collectively grappled to understand both its promise and its peril. Central to that battle for equilibrium has been the Nuclear Weapons Non-Proliferation Treaty, a bedrock of global security since its establishment in 1968. The legal structure of the Non-Proliferation Treaty aims to stop the proliferation of nuclear weapons, promote disarmament and with exceptions help spread peaceful nuclear cooperation. But in a world that is in tension, the usefulness of the treaty is being increasingly questioned as tensions around the globe escalate and new powers emerge.

Iran’s recent announcement that it might leave the Non-Proliferation Treaty in the face of Israeli bombings, and following an International Atomic Energy Agency resolution responsible for condemning Iran, has further caused worries about the enforcing capabilities of the treaty. Nuclear aspirations in Asia more generally, with North Korea’s developing capabilities and increasing discussions over nuclear deterrence in South Korea and Japan, have similarly put question marks on the ability of the Non-Proliferation Treaty to respond adequately to current security developments. With the changing geopolitical landscape and non-signatories states acting outside the treaty’s commitments, the “pressure to ensure that the Non-Proliferation Treaty remains a relevant and effective instrument” becomes sharper.

The Legal Backbone of the Non-Proliferation Treaty

The Non-Proliferation Treaty is one of the most widely ratified arms control treaties in the world, with 191 states party since it entered into force in 1970 . Around what are known to be the three pillars: non- proliferation, disarmament and the peaceful uses of nuclear, is constructed the legal framework. These pillars are evident in the 11 Articles of the treaty which enjoin responsibilities on both nuclear weapon states (NWS) and non- nuclear weapon states (NNWS).

Article I deals with the commitment of Nuclear-Weapon States (the United States, Russia, China, France, and the United Kingdom) to Refrain from Transfer, Assistance or Inducement Related to Nuclear Weapons do not transfer nuclear weapons and not assist Non-Nuclear Weapon States in acquiring them. Under Article II, it is the obligations of Non-Nuclear-Weapon States to Refrain from acquisition, manufacture and assistance in nuclear weapons. This legal bifurcation privileges the weapons of the nuclear weapon states while denying others membership of the nuclear club. Moreover, Article VI commitment to nuclear disarmament and ending the arms race through good-faith negotiations and while Article IV deals with right to peaceful use of nuclear energy and international cooperation for development.

As part of its Article III, parties commit to safeguards and verification measures to avoid the diversion of nuclear energy from peaceful to military ends. In order to ensure that they are not diverting materials for weapons, these agreements mandate that non-nuclear weapon states submit their nuclear operations for International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspections. Thus, the Non-Proliferation Treaty ‘s legal framework strikes a balance between strong controls to stop proliferation and incentives for access to peaceful nuclear technology.

Achievements and Strengths

The legal framework of the non-proliferation treaty has thus been extraordinarily successful. It has made proliferation unacceptable and thus limited the nuclear club to the nine states that now have nuclear weapons, a much smaller number than what was predicted during the Cold War. The Non-Proliferation Treaty also led South Africa, Ukraine and Kazakhstan to abandon or not pursue nuclear weapons. The treaties, under the International Atomic Energy Agency, have a safeguards system that aims to identify and preclude violations but mainly aims at increasing the transparency of nuclear programs.

Every five years, the conference of the Treaty’s Parties reviews its implementation, which gives states a legal way to evaluate their progress and resolve issues. Even where consensus has been difficult to achieve, such meetings are useful in keeping the normative force of the treaty itself. The fact that non-proliferation treaty is capable of striking a balance between security concerns with development goals is proved by countries such as South Korea and Japan who have developed robust civilian nuclear programs under strict scrutiny by virtue of right to peaceful nuclear energy laid down by international law.

Challenges and Legal Tensions

Despite its successes, the non-proliferation treaty is confronted by legal as well as geopolitical challenges that undermine its legitimacy. The most obvious of these is the failure of disarmament under Article VI. The nuclear weapon states have downsized from their Cold War height, yet modernization, including new warhead development by the U.S. and hypersonic nuclear-armed missiles by Russia, erodes any disarmament momentum. The non-nuclear weapon states, especially those in the Global South, maintain that NWS non-compliance of their Article VI obligations sustains an uneven nuclear order that violate the treaty’s legal intent.

Non-compliance is another hurdle. In 2003, the North Korea’s nuclear test and subsequent pullout from the pact shows the weakness of the treaty’s enforcement mechanisms. The non-proliferation treaty relies on diplomatic measures and referrals to the International Atomic Energy Agency, but there are no teeth, although the UN Security Council could authorize them. Disputes have also challenged the legal limitations of the treaty, like whether Iran’s enrichment program is a violation of Article II or it falls under the stipulations of Article IV for peaceful purposes.

The nuclear order is made even more complex by the rise of non-signatory nations like North Korea, Israel, Pakistan and India. These countries, who do not are bound by the legal obligations of the non-proliferation treaty, have accumulated nuclear weapons, bringing into question the universality of the treaty. Pointing out to a structural flaw, namely that the Non-Proliferation Treaty recognizes only five Nuclear Weapons States based on a situation in 1968, excluding newer nuclear states and creating a legal grey zone.

Global Tensions and the Non-Proliferation Treaty’s Future

Today’s geopolitical landscape amplifies these challenges. Distrust arising from the U.S.-Chinese rivalry, as well as from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and Iran’s search for hegemony in the region render disarmament negotiations extremely difficult. Concerns over new technologies like cyber and AI and their risk for nuclear command-and-control systems, as well as worries about the ability of the non-proliferation treaty to remain relevant in the 21st century. In harmony with the discontent of the non-proliferation treaty process stalemate about disarmament, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was opened for signature in 2017 being endorsed by 69 non-nuclear states, though its legal ramifications are minimal as it has not yet been adopted by any of the Nuclear Weapons States (NWS).

There are enforcement gaps in the Non-Proliferation Treaty’s legal framework as well. The International Atomic Energy Agency also counts on state support in order to safeguard the integrity of its safeguards, and as it has been the case in the past, political tensions in the UN Security Council impede the agency from taking certain measures against violators. Against fortifying the treaty via automatic penalties for non-compliance or a verification system for disarmament are the stronger reluctant to relinquish sovereignty states.

Toward a Resilient Nuclear Order

The non-proliferation treaty is an important piece of legislation and an important stride forward, though a mending of the flaws is a means of its survival. But, this is a broad discussion of what a better implementation of Article VI may look like and would need to be more specific in terms of actions, such as, for instance, raising the issue of U.S.-Russian arms control negotiations or engaging China in a multilateral arms control discussion. One way to improve non-proliferation could be to reinforce the authority of the International Atomic Energy Agency, perhaps through universal safeguards or new monitoring technologies. Collecting them in order to engage non-signatory states and close the gap toward universality could involve incentives like regional security dialogues.

Ultimately the strength of the legal framework of the Non-Proliferation Treaty is politically dependent. With international tensions rising, this treaty’s success is dependent on finding a compromise between Nuclear-Weapon States responsibilities and Non-Nuclear-Weapon States aspirations. If the principles that underpin the nuclear order are not reinforced, the nuclear order will fragment and the world will experience the catastrophic consequences of proliferation. The Non-Proliferation Treaty has its flaws but is still “the best legal bulwark we have against nuclear war” a thin bulwark indeed, but better than nothing in these unpredictable era.

References:

Megna Devkar is a Ph.D. Research Scholar at K.C. Law College with research and writing expertise in social, political, and legal issues. Views expressed are the author’s own.