- Medog grants China the ability to shape outcomes in India’s Northeast and Bangladesh without firing a shot.

- For India and Bangladesh, the primary concern is not overall annual river flow, which is driven by the monsoon, but when and how water is released.

- In 21st-century Asia, rivers are not just sources of water but also instruments of power, comparable to missiles or trade routes.

On July 19, 2025, Chinese Premier Li Qiang presided over the ground-breaking of the Lower Yarlung Tsangpo/Medog Hydropower Project. The event was portrayed as a milestone in clean-energy ambitions. But for India and Bangladesh, Medog is not only a symbol of China’s technological prowess; it is also a clear reminder that hydropower today is deeply linked to geopolitics and security concerns.

Rising at the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo, where the river falls nearly 2,000 meters through the world’s deepest canyon, Medog is designed to be the most powerful hydropower project in the world. With a projected 60,000 MW installed capacity and an annual output of around 300 TWh, Medog will generate three times more power than the Three Gorges Dam and nearly sixty times India’s Tehri Dam. Costing between $137–170 billion, it stands as a landmark example of ambitious infrastructure planning.

Medog in Context: A Long-Term Strategy

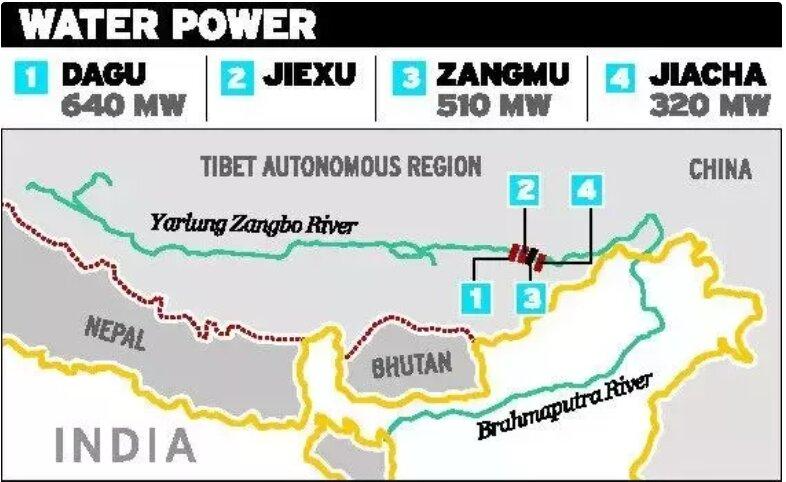

To understand Medog, one must see it as the result of a long-term upstream strategy pursued by China. This project does not stand alone. Over the past decade, China has quietly constructed a chain of dams along the Yarlung Tsangpo: the Zangmu Dam (510 MW, 2015), the Jiacha Dam (360 MW, 2020), and the Dagu Dam (~640 MW, 2023). Additional projects, such as Jiexu (560 MW) and Bayu (780 MW), are in the pipeline.

Together, these installations serve two purposes: they generate power for Tibet’s grid, and they build operational capacity and political leverage for China. Medog is the logical next step, an apex project that provides China not only energy but also command over the timing and sediment of water flows, a tool with profound geopolitical consequences.

Together, these installations serve two purposes: they generate power for Tibet’s grid, and they build operational capacity and political leverage for China

A Matter of Scale

The scale of Medog becomes clearer when placed alongside other mega-dams:

| Project | Installed Capacity | Annual Generation | Established | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medog (China) | 60,0000 MW | ~300 TWh | 2030s (est.) | $ 137-170 bn |

| Three Gorges (China) | 22,500 MW | ~100 TWh | 2006 | $ 31 bn |

| Tehri (India) | 1000 MW(+1000 MW PSP) | ~3 TWh | 2006(+PSP 2025) | $ 2.5 bn |

- Medog will dwarf not just India’s Tehri but also China’s own Three Gorges. For downstream countries, this asymmetry is not simply about electricity; it is about bargaining power.

Impacts on the downstream: Timing, Variability and Sediment concerns

For India and Bangladesh, the primary concern is not overall annual river flow, which is driven by the monsoon, but when and how water is released.

In the Brahmaputra basin, livelihoods depend on predictable flows and nutrient-rich silt. Large upstream dams risk altering this delicate balance. Sudden water releases could trigger devastating floods in Assam, while excessive storage could leave farmers struggling with dry-season scarcity. Moreover, sediment trapping by large reservoirs can reduce soil fertility downstream, threatening agriculture in both India and Bangladesh.

Bangladesh, acutely vulnerable to river changes, has already requested environmental and disaster-related studies from China but has yet to receive comprehensive responses. The lack of transparency only deepens unease.

The Data Gap: From Confidence to Blind Spots

For years, India and China relied on seasonal hydrological data sharing under the Expert-Level Mechanism (ELM). But the agreements lapsed:

- Brahmaputra MoU expired in June 2023.

- Sutlej MoU expired in November 2020.

- India reports receiving no Chinese flow data since 2022.

This means India’s flood forecasting systems are working blind. In South Asia, where floods affect millions annually, this isn’t just negligence; it’s a strategic risk.

Bangladesh, acutely vulnerable to river changes, has already requested environmental and disaster-related studies from China but has yet to receive comprehensive responses.

Seismic and Ecological Risk

The Yarlung Tsangpo Grand Canyon is rich in biodiversity but also lies in an earthquake-prone zone. Experts in Assam warn that if dams trap too much silt, the released water becomes “hungry water,” which can erode riverbanks faster and damage habitats. It also carries serious natural risks like sudden water releases, emergency drawdowns or floods from landslides, dam bursts upstream that could affect countries downstream.

Thus, while Medog may be seen as an engineering marvel, it also sits atop a fragile ecological and geological foundation.

Strategic Implications: Water as Deterrence

Medog elevates water management into the realm of strategic deterrence. Unlike conventional weapons, dams offer subtler, deniable tools of pressure:

- In the dry season, withholding flows could deepen India’s water stress.

- During monsoons, sudden releases could destabilise downstream regions.

- By trapping sediment, China could erode the agricultural fertility of Assam and Bangladesh.

In other words, Medog grants China the ability to shape outcomes in India’s Northeast and Bangladesh without firing a shot.

Plausible Scenarios (2025–2035)

- Managed Stability: China runs the Medog dam with clear rules, small storage and real-time data sharing through a stronger ELM. Flood and drought risks stay under control, while India’s Upper Siang project adds extra safety.

- Friction & Floods: If data sharing stays suspended and extreme monsoons or earthquakes hit, sudden flow shocks could harm downstream areas. Even without hostile intent, water could become a political flashpoint.

- Institutional Reset: India, China, and Bangladesh agree on a trilateral basin authority, separating water safety from sovereignty disputes.

Policy Recommendations

Moving beyond ad hoc MoUs is no longer sufficient if the Brahmaputra is to evolve into a platform for cooperation rather than conflict. China must take the lead in building trust by releasing comprehensive environmental impact studies, publishing transparent dam operation protocols and restoring real-time hydrological data exchange under a binding agreement. India, for its part, needs to accelerate the Upper Siang project, but in a manner that incorporates ecological safeguards such as sediment management systems, minimum environmental flows, robust flood-control measures in Assam and enhanced water storage for the dry season. Bangladesh, meanwhile, must adapt by fortifying its defences against flooding and salinity intrusion, while pressing for greater transparency at the basin level.

Ultimately, the only durable solution lies in all three riparian nations working toward a Brahmaputra Basin Authority, anchored by independent experts, a shared data platform, and joint disaster-response drills so that this river becomes not a source of rivalry but a model of cooperative governance.

To conclude, Medog highlights a hard truth: in 21st-century Asia, rivers are not just sources of water but also instruments of power, comparable to missiles or trade routes. The expiry of data-sharing in 2023 shows that India cannot depend on China’s goodwill. India’s water security will depend on building resilience at home, deepening cooperation with its neighbours and pursuing long-term planning independent of China. For Bangladesh, survival requires balancing adaptation with smart diplomacy. For China, the choice is whether Medog becomes a symbol of clean energy or a lever of pressure. Handled wisely, the Brahmaputra could be a model of cooperation. If not, it could turn into a source of conflict, where natural flows are weaponised.

References:

- https://madeinchinajournal.com/2025/08/07/infrastructure-and-state-building-chinas-ambitions-for-the-lower-yarlung-tsangpo-project/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002216942401998X

- https://www.waterpowermagazine.com/news/china-approves-construction-of-worlds-largest-hydropower-dam-in-tibet/

- https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/china-has-not-shared-river-data-with-india-since-2022-rti-query-reveals-exclusive-2731993-2025-05-28

- https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-build-worlds-largest-hydropower-dam-tibet-2024-12-26/

- https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/china-embarks-worlds-largest-hydropower-dam-capital-markets-cheer-2025-07-21/

- https://www.usip.org/publications/2022/12/water-wars-myth-india-china-and-brahmaputra

- https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/china-has-not-shared-river-data-with-india-since-2022-rti-query-reveals-exclusive-2731993-2025-05-28

- https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/china-embarks-worlds-largest-hydropower-dam-capital-markets-cheer-2025-07-21/

- https://www.telegraphindia.com/world/after-india-bangladesh-seeks-answers-from-china-on-medog-dam-in-brahmaputra/cid/

Tejashree P V holds a Master’s degree in English Literature from IGNOU and a Bachelor’s degree in Journalism, English, and History from Vivekananda Degree College. A UPSC aspirant, she has a keen interest in international affairs, geopolitics, and policy.