- China’s strategic retreat may be read as a pragmatic response to mounting economic, security, and institutional risks enveloping Pakistan.

- Faced with Beijing’s refusal, Islamabad is now turning to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for a $2 billion loan to upgrade the Karachi–Rohri stretch, part of the broader 1,800 km ML-1 corridor from Karachi to Peshawar.

- While CPEC was envisioned as transformational, it became a casualty of misaligned governance, corruption, and institutional fragility.

- China’s partial disengagement creates breathing room, but it does not remove the strategic logic of Sino-Pakistani cooperation.

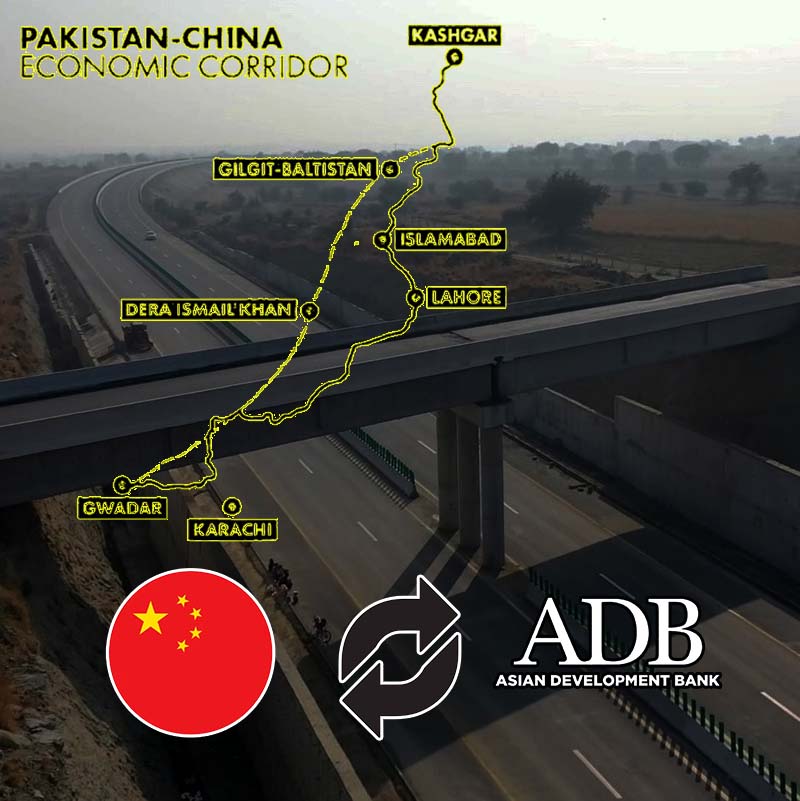

In early September 2025, China’s withdrawal from financing the pivotal Main Line-1 (ML-1) railway upgrade, a cornerstone of the $60 billion China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), became public. Reports confirm that Beijing has declined to back the Karachi–Rohri segment—formerly expected to receive around $2 billion—from its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) portfolio. This marks a substantive strategic recalibration: what was once the richest and most ambitious infrastructure partnership between the two “all-weather allies” now appears to be fraught with financial reservations and geopolitical complexity. China’s reasons are multifaceted but compelling. Beijing is grappling with its own economic headwinds, prompting a broader retrenchment from high-risk, large-scale overseas commitments. Pakistan, deeply ensnared in economic distress—marked by soaring debt, repeated IMF bailouts, and growing arrears to Chinese power producers—has increasingly become a fiscal risk that tests China’s tolerance for exposure. Moreover, equal emphasis must be placed on security: persistent attacks on Chinese nationals within Pakistan, especially in volatile Balochistan, have further tarnished the project’s appeal.

This withdrawal is both pragmatic and symbolic. CPEC’s early momentum—culminating in highway, port, and energy infrastructure victories between 2015 and 2019—has largely stalled, with Gwadar’s full potential still unrealised, and headline deployments lacking substance. ML-1, initially billed as transformative, is now emblematic of stagnation rather than promise. Thus, China’s strategic retreat may be read as a pragmatic response to mounting economic, security, and institutional risks enveloping Pakistan.

Pakistan Turning to the ADB—Diversification or Desperation?

Faced with Beijing’s refusal, Islamabad is now turning to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) for a $2 billion loan to upgrade the Karachi–Rohri stretch, part of the broader 1,800 km ML-1 corridor from Karachi to Peshawar. This marks a historic first: a multilateral institution stepping in to finance a core infrastructure project originally designed as a flagship of the BRI. For Pakistan, this pivot is driven as much by necessity—its faltering economy and Chinese arrears—as by strategic repositioning. The urgency is underscored by the Reko Diq copper-gold mining venture in Balochistan, led by Barrick Gold, which demands robust logistics to channel heavy mineral output to ports. Without a modernised ML-1, the mine’s immense export potential remains hostage to fragile rail connectivity. The ADB has already pledged $410 million toward infrastructure linked to Reko Diq, signalling its intent to support Pakistan’s long-term export infrastructure. Yet, this shift carries risks for Pakistan. Rising debt, now to the ADB, may only compound existing fiscal stress. Indeed, some reports indicate that Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif is under political duress—a metaphorical “begging” for loans from the ADB has become inevitable. This moment may reveal both resilience and desperation: while diversification of financing sources is sensible, it could also signify that Pakistan has outlived China’s faith in its governance and economic stewardship.

Underlying Failures—Why CPEC Faltered Beyond Finance

Even as Beijing steps back, an equally compelling narrative emerges: the failure lies not just with external financiers but also Pakistan’s own systemic mismanagement. A critical foreign policy analysis underlines this harsh reality: more than half of CPEC’s envisioned projects remain incomplete—only 38 of nearly 90 projects finished, 23 in progress, and about one-third untouched. Infrastructure deliverables like Special Economic Zones (SEZs), intended to spur industrial growth, have either underdelivered or been abandoned altogether. Instead, Pakistan frequently diverted CPEC funds into politically visible urban projects—such as Lahore’s metro train—that offered little in the way of export potential or structural transformation. Gwadar, while breaking ground with a new airport, remains underutilised, lacking passenger and commercial traffic amid ongoing security issues and local discontent. Chinese investment in Gwadar still hovers around a paltry $890 million—a small fraction of total CPEC potential. Security threats have become too tangible to ignore: over the past several years, more than a dozen attacks targeting Chinese nationals have occurred, resulting in multiple fatalities and heightened concern from Beijing. Combined with rampant bureaucratic inertia and political short-termism, these issues fundamentally undermined investor confidence—both domestically and with China. While CPEC was envisioned as transformational, it became a casualty of misaligned governance, corruption, and institutional fragility.

Broader Implications—Geopolitics, Economic Sovereignty, and Strategic Realignment

China’s partial disengagement from CPEC reverberates beyond economics—it reshapes geopolitical alignments in South Asia and highlights Pakistan’s precarious balancing act. Islamabad’s delicate diplomacy is evident in its carefully measured communication that shifting to multilateral lenders was coordinated with Beijing, ensuring that the symbolic “iron-clad friendship” remains intact. Yet, shifting to Western-aligned institutions such as the ADB—and potentially leveraging U.S. interest in Reko Diq—contours are changing. This pluralist financing, if sustained, could benefit Pakistan by diversifying dependency and reducing unilateral vulnerability. However, the path is treacherous. Rising US-China tensions and the warming of India-China ties create an environment where Pakistan’s strategic autonomy is increasingly squeezed. Internally, the country must confront its economic over-reliance on external debt, energy load shedding, and debt servicing burden—particularly to Chinese power producers, which remains a crippling drain on public finances. China’s change of heart might also presage a broader Belt and Road strategy recalibration. As institutional capacity issues come to the fore in BRI partner countries, and as financiers reassess risk, China may divert investment to more stable or strategically profitable arenas, recalibrating its global outreach. For Pakistan, the window to reinvent its role in the geoeconomic landscape remains open—but only if it overcomes structural pitfalls and demonstrates transparent governance.

Path Forward—Lessons, Reforms, and the Road Ahead

Looking ahead, Pakistan must treat this moment as both a cautionary tale and an opportunity. The CPEC saga elucidates that infrastructure partnerships—no matter how grand—grossly falter without robust governance frameworks, institutional capacity, and political will to deliver long-term economic value. Moving forward, Islamabad must embed transparency, streamline bureaucracy, and weather the unglamorous but critical task of institutional reform; only then can it attract and effectively utilise strategic capital. On the strategic front, diversifying funding sources is prudent, but not sufficient unless accompanied by fiscal discipline and energy sector reform—the latter especially urgent, given the historic burden of unaffordable Chinese-financed power projects that contributed to national debt and public misery. Environmental sustainability should also be elevated; CPEC’s coal legacy undermines both climate commitments and financial stability. Internationally, Pakistan must navigate its triangular engagement between China, emerging Western interests, and regional actors. Preserving cordial ties with Beijing remains vital, but it must now be balanced with constructive partnerships with multilateral institutions and new stakeholders, anchored by shared economic interests—not just geopolitical symbolism. China’s partial retreat from CPEC illustrates that infrastructure ambition alone cannot compensate for governance deficits. Pakistan’s failure to internalise this truth risks not just the loss of foreign capital, but its own economic sovereignty. Yet, if it seizes this corrective moment, tightens governance, and adopts sustainable development models, it may still recast its trajectory—transforming a faltering partnership into a foundation for resilient growth and diversified diplomacy.

India’s Strategic Takeaways from China’s Partial Exit from CPEC

For India, China’s partial retreat from the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) opens up both opportunities and challenges that require careful watching. On the positive side, Beijing’s visible reluctance to continue pouring funds into Pakistan weakens the central strategic rationale of CPEC—giving China unfettered access to the Arabian Sea through Gwadar. For years, Indian security planners viewed CPEC as a dual-use infrastructure project with deep military and geoeconomic implications, especially as it traversed through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). A slowdown, or even partial disengagement, alleviates immediate concerns about rapid militarisation or large-scale Chinese naval presence in Gwadar. It also suggests that China is recalibrating the Belt and Road Initiative toward more profitable and stable geographies, which could blunt its aggressive economic outreach in India’s neighbourhood.

At the same time, India cannot afford complacency. The very fact that Pakistan is now turning to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Western-aligned institutions for funding signals a potential diversification of Islamabad’s economic partnerships. If effectively managed, this could reduce Pakistan’s overdependence on Beijing and open space for external powers, including the U.S., to reassert influence. This might alter the geopolitical dynamics of South Asia, especially if Pakistan leverages new partnerships to stabilise its economy and rebuild capacity. India must monitor whether such diversification dilutes Chinese leverage or merely adds more creditors to Pakistan’s already fragile debt profile.

Finally, the security dimension remains crucial. Despite Chinese frustration, Beijing will not abandon Pakistan entirely, as Islamabad remains strategically valuable in countering India. India must therefore remain vigilant against covert or smaller-scale Chinese investments in sensitive areas like PoK, Balochistan, or Gwadar. In essence, China’s partial disengagement creates breathing room, but it does not remove the strategic logic of Sino-Pakistani cooperation. India’s response should combine strategic caution with proactive regional engagement.

Dr. Nanda Kishor M. S. is an Associate Professor at the Department of Politics and International Studies, Pondicherry University, and former Head of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal University. His expertise spans India’s foreign policy, conflict resolution, international law, and national security, with several publications and fellowships from institutions including UNHCR, Brookings, and DAAD. The views expressed are the author’s own.