- The survival imperative lies at the core of the ‘innovate or perish’ dictum, and is based on the principle that nothing is permanent and, consequently, since there is no one way of doing things, the continuous quest is in finding a better way.

- Today, innovation is no longer perceived as a peripheral activity but rather as a determinant of national power and an integral part of a nation’s DNA.

- Indeed, a nation’s global standing and influence are now shaped decisively by control over technologies, standards, platforms, and supply chains.

- Innovation is figuring out how something can be done better and how new technologies can be harnessed to create new offerings.

Human societies constantly examine and re-evaluate the way they do things, so that they might survive better. Shaping a stone and sharpening it to make a dagger or fixing it to a long stick to make a spear is innovation, as it allowed them to hunt better and protect themselves against enemies. Moving from a shelter made with branches and leaves to a cave or mud house, for instance, that protected them against inclement weather and wild animals is, similarly, an innovation. This kind of shift in thinking and acting has been part of human society since time immemorial. Yet, we have taken it for granted and never once wondered if innovation did not occur, what might have been the nature of human civilisation.

The survival imperative lies at the core of the ‘innovate or perish’ dictum, and is based on the principle that nothing is permanent and, consequently, since there is no one way of doing things, the continuous quest is in finding a better way. Added to this is the rapid pace at which technological changes are occurring. Keeping pace, then, is a compulsion and not a choice. Alvin Toffler, in his book Future Shock, argued that tectonic developments in technology will disrupt the present and give the future an accelerated push. Those, he asserts, who are unprepared and thus unable to adjust to and accommodate this would be swept aside and rendered irrelevant. Kodak, it may be recalled, disappeared from the market simply because it refused to anticipate the future and cater to it.

Today, innovation is no longer perceived as a peripheral activity but rather as a determinant of national power and an integral part of a nation’s DNA. The ability of a nation, in other words, to innovate technologically, institutionally and culturally, increasingly defines its geopolitical relevance, economic sovereignty and strategic autonomy. While borders are still defended by armies, the very future of war has dramatically changed through technological advancements. Indeed, a nation’s global standing and influence are now shaped decisively by control over technologies, standards, platforms, and supply chains.

Having said this, before we embrace innovation, it is necessary to demystify it so that we might better understand what it implies. At one level, many fear innovation because they fear change. This is a fairly common affliction because of the risk associated with change. We get used to doing things in a particular way, and any disruption is seen as triggering uncertainty and challenging our comfort zone. This causes anxiety because of the fear of failure. After all, not all innovations succeed. Indeed, most fail. Related to this is the fear of irrelevance. Many perceive change as a threat to their jobs and a pointer to the need for fresh blood and new ways of seeing that they feel they are incapable of. It is like dusting away the obsolete and can certainly cause fear. At a third level, it has become fashionable for CEOs, politicians, and bureaucrats to speak of the need to usher in disruptive change, without quite knowing what it entails. They incorporate such terminology into their vocabulary because they feel compelled to do so, as if it would otherwise project them as not being futuristic. Indeed, the pressure has become so oppressive that many have started to complain of change-fatigue, which has come as a big relief to the naysayers of innovation.

Notwithstanding such resistance, innovation has now become an indispensable part of company policy, whereby an ‘innovation culture’ is fostered among its employees. Competition in the marketplace makes it imperative for companies to constantly put up new offerings to their customers, as the objective is not merely to survive but rather to thrive. Mobile phones, for instance, dramatically changed when they incorporated cameras. Power steering in cars was another significant innovation. Companies die when they start to stagnate. Like Kodak, Nokia and Blackberry, which were once household names, vanished from the marketplace because they refused to innovate, take advantage of new technologies, and ignore customer needs. It is almost as if they had chosen to commit hara-kiri. Competitive edge is only achieved when companies use changing technologies to respond to evolving customer demand.

Innovation is not merely the mechanical pursuit of a better idea and attempting to think outside the box, as the cliché recommends. Rather, it is that next big step into the unknown that makes all the difference! Innovation is figuring out how something can be done better and how new technologies can be harnessed to create new offerings. It is the leap from idea to execution. Google, for instance, is a great idea because Google exists and Google works. In other words, innovation needs to make the transition from idea to a compelling business proposition. Or to put it differently, innovation succeeds only if it helps in doing things more efficiently and thus, in being seen as a growth enabler and a value proposition.

It is worth recalling that, according to available data, the average life span of most companies is around twenty years. This is because most companies prefer to stick with what they know – ‘the tried and tested’. They refuse to learn how to see through the fog and what pitfalls lie ahead, and thus, to anticipate change and prepare for it. At the heart of the entrepreneurial spirit lies innovation. According to the economist Joseph Schumpeter, the entrepreneurial spirit embodies ‘creative destruction’, whereby entrepreneurs become agents of change not only by anticipating and responding to changing market demands but also by creating new demand. The smartphone replacing the landline, or streaming replacing traditional media, or audiobooks replacing printed books are good examples of innovation. Entrepreneurs disrupt and are not afraid to do so. Indeed, in corporate culture, competition is the biggest pitfall that companies must cope with. Companies fail because they are unable to redefine themselves, whereas some of their competitors can do so.

Innovation is not restricted to business enterprises alone. The White Revolution, for instance, was an extraordinary development initiative that converted India from a milk-deficient nation into the largest milk-producing country in the world by establishing a milk-grid through village-level milk producers’ cooperatives, directly linking producers to consumers, and cutting out the middlemen. The impact of the revolution was far-reaching. It empowered the rural milk-producing community, more than doubled the availability of milk in the country, improved nutrition and animal husbandry, embraced technology, and created a national milk grid. India’s success inspired several developing countries to follow the ‘India model’.

In the educational field, the Montessori school system was a revolutionary innovation in teaching methods, whereby children chose what they would learn and trained teachers played the role of facilitators. Games were incorporated as part of pedagogy through hands-on experiential learning, rather than the excessive reliance on books. Similarly, the Madras Method introduced in Britain by Andrew Bell and Joseph Lancaster was a pioneering innovation, through which senior students (also called ‘monitors’) taught their younger peers. It allowed for mass education by training bright young senior students as ‘mini-teachers’. The model was co-opted for mass school education in Britain and beyond, especially at a time of teacher shortage, as the use of monitors acted as an instant augmentation of teaching staff.

Innovation is widespread in the defence industry. The stealth bomber, for instance, is a path-breaking innovation that has transformed air warfare by incorporating stealth technology and advanced aerodynamics to carry out deep strike missions undetected. Nuclear submarines are, similarly, a significant innovation enabling unlimited range and stealth. They provide strategic depth and deterrence by vastly enhancing strike capability, while remaining undetected. In a similar vein, the Uzi and the Kalashnikov (AK-47) are major innovations that have transformed modern warfare. With the emergence of new technologies, the future of warfare will undergo profound changes through the use of digital warfare, artificial intelligence, robotics, and laser-based weaponry, in addition to traditional weapons with enhanced lethality and stealth, such as tanks, ground troops, aircraft, and navies.

Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson argue that even nations fail if they do not innovate and adapt to changing circumstances or if they fail to read the signs of public discontent. History is full of examples of blinkered vision in leadership and governance, leading to coups and the overthrow of existing power structures. Idi Amin’s welcome ouster was preceded by his inability to read the simmering anger among his own people against his lavish lifestyle and brutal governance. In 1979, the Shah of Iran was overthrown because he ruthlessly clung to authoritarian rule and subjugated his dissenters to inhuman conditions, torture, imprisonment, and death. When the revolution came, the Shah had to flee or face the wrath of his people, like the Romanovs, who were executed following the Russian revolution. The list is endless, from colonial brutality to the Arab Spring. Nations fail because the leadership is blindsided by arrogance and power, and flatly refuses to read signs even when they are staring them in the face. It is this disconnect that leads to their downfall. When elections are held in democracies or when dictatorships and oppressive regimes fail to listen to their people, change occurs as a response to bad governance.

Innovation challenges established thinking. It is, as the poet Robert Frost so wonderfully put it, taking the road less travelled by. Edward de Bono referred to it as the freeing up of imagination or lateral thinking. It is ‘the art of looking sideways’, to borrow Fletcher Alan’s phrase. Consider the contrast between President Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe (formerly known as Rhodesia) and President Nelson Mandela of South Africa. One is considered a pariah by the white community, while the other is an international icon. The circumstances that both leaders inherited were the same – white immigrant settlers, who imposed racial discrimination and segregation with a heavy hand. Cecil Rhodes, after whom Rhodesia was named, oversaw much of this and is said to have also participated himself. The situation was no different in South Africa. Mandela’s incarceration and what he was forced to go through for twenty-seven years in jail are testimony to the brutality the white settlers were capable of and the racial hatred against black Africans. Men, women, and children were indiscriminately shot. The indigenous African population was deprived of their land and made to work as slaves. There were pavements where blacks were not allowed to walk on, and designated seats for them on buses, and marketplaces where they were denied access. Sovereign nations were deprived of their dignity. Their people were treated worse than animals. Yet, even today, no international human rights commission or court of justice has ruled on colonialism and how it emasculated an entire people, who were not white. Even becoming Christian did not help them.

Following independence from colonial rule, Mugabe was initially benign towards the white settlers, but changed as he read the sentiment of the rioting black community. He allowed them to attack and loot white homes and even deprive them of their properties. Some white settlers lost their lives. Vengeance became the mantra, and for good reason. The oppressed black African community, many of whom had lost their land and seen family members massacred by the white immigrants and the white police, sought revenge. Mugabe encouraged this.

Mandela, on the other hand, opted for an alternative and innovative strategy of reconciliation. He wanted to unite South Africa – whites and blacks – to create a new South Africa, based on tolerance, brotherhood, and collective aspiration. He forgave his jailors, including those who had tormented him. It sounded crazy, but it was, in fact, a revolution in thought. While Mugabe acted along expected lines (vengeance), Mandela broke the mould (reconciliation) and thought differently. He was the square peg in the round hole.

Great leadership recognises the significance of innovation and the need to nurture it. In the words of Steve Jobs, ‘Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower. Mandela was an innovator, as was Martin Luther King Jr., or Mother Teresa. Mahatma Gandhi was an innovator because his advocacy of non-violence and civil disobedience to counter the violence of colonial oppression went against the norm and the expected. It was a paradigm shift in thinking, and yet, it won India freedom from colonial rule. History is unforgiving to leaders who fail to innovate.

At the same time, it is important not to misread the emphasis on innovation as a call to make it a fetish and a mechanical exercise. Innovation works only if it enhances efficiency when it addresses a pressing concern. The emphasis overload can, however, drive many companies to force employees to find alternative ways of doing things without any value creation. Such dangers can be avoided only when leadership recognises why there is a need to innovate and in which areas.

But it is also true that countries are considered laggards if they resist innovation. Stagnation, irrelevance, and ultimately, demise, then, become inevitable. Consider developing countries, for instance. The route of transformational upliftment that they choose will determine their future for generations to come. In today’s global order, power is no longer defined only by military strength or economic size. It is increasingly shaped by a nation’s capacity to innovate, to create, scale and secure critical technologies that determine strategic autonomy, economic resilience, and diplomatic leverage. In other words, developing countries need to understand that innovation is no longer a development choice; it is, in fact, a geopolitical necessity.

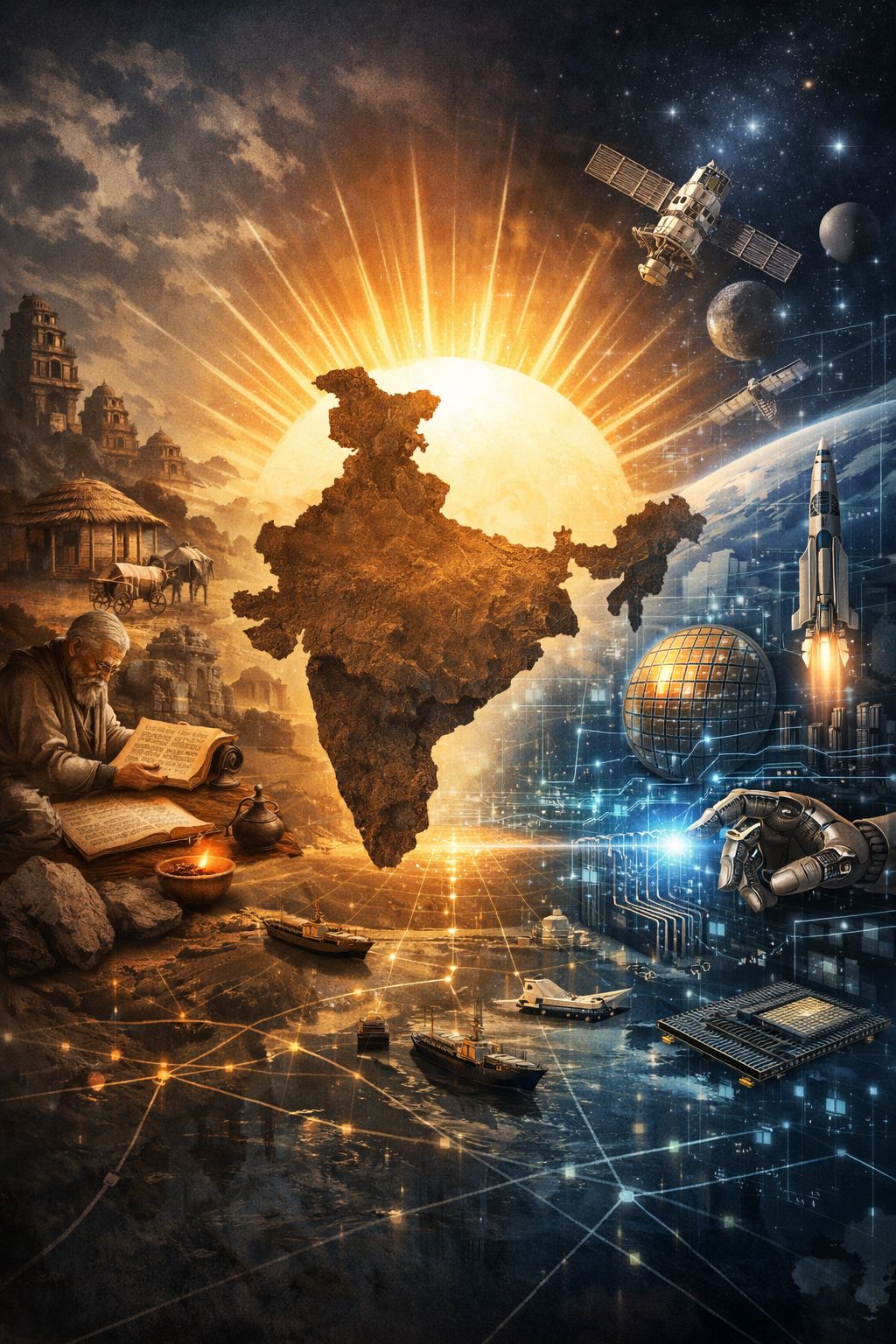

Consider the case of India, for instance. Her strategic context is unique. It is not a treaty ally embedded in a single bloc, nor is it insulated from global shocks. It must manage a contested land border, secure vast maritime interests in the Indo-Pacific, and engage simultaneously with competing technology ecosystems led especially by the United States and China, and to some extent, by Europe. This imposed reality has sharpened India’s emphasis on strategic autonomy, or the ability to act independently in its national interest. But assertion of strategic autonomy in the 21st century is not sustained by diplomacy alone but driven substantially by technological capability.

This requires control over semiconductors, digital platforms, energy technologies, space systems, defence equipment, and data infrastructure, which would increasingly determine:

- Supply-chain security,

- Military preparedness and capabilities, and

- Economic resilience

The negotiating power in international fora to manage all the above is equally critical. In this sense, innovation has become an extension of foreign policy.

Unfortunately, for decades, research and innovation were never a key focus in India’s educational institutions or part of government policy. Curiosity and critical thinking were viewed with suspicion and seen as an aberration. Bright students, whose parents had the financial wherewithal, moved to the US for higher studies and enrolled in institutions where fostering research and innovation were embedded in their DNA. They did well and gained recognition, like Sundar Pichai, for instance.

But here in India, nurturing the research and innovation culture has been absent in schools and colleges because it was not perceived as a strategic and enabling requirement of government policy and statecraft. Jugaad, or finding cheap and improvised solutions to avoid replacement, emerged instead, and while it has its plus points, it is certainly not a substitute for innovation.

It is this context that it is argued that one of India’s great drawbacks has been its lack of investment in R&D as a percentage of GDP. India’s Gross Expenditure in R&D (GERD) stands at an abysmal 0.66%, and when compared, for instance, to Israel, which is 2.61%, the US, which is at 3.43%, and Germany, which is at 3.1%. India compares poorly. Consider also that Israel has a population of eight million people compared to India’s 1.4 billion, and further, Israel has produced twelve Nobel laureates, including several more of Jewish descent, whereas India can lay claim to hardly any, other than Tagore. This is a telling statistic because it is reflective of the low priority India has given to research and innovation. Unless there is a strategic shift in mindsets and government policies, India will find it challenging to achieve its strategic objectives and aspirations.

A comparison with China would be sobering and certainly not out of place, especially since China is often referred to as a country in a perpetual state of innovation. Shenzhen, for instance, was a massive factory city churning out cheap goods for the world. Today, it has pushed boundaries and rewired itself to become home to global giants. It is expanding further and has emerged as China’s gateway to 5G and the ‘Internet of Things’. Chengdu is, similarly, another powerful story, where the interface of science and technology drives the passion for innovation. Indeed, as many have documented, China’s strategic clout in global affairs and its economic success story are built around its innovation hunger. Consequently, nurturing it has become part of government policy, enabling it to explore markets well beyond its borders, so as to fuel the innovation flame that will further spur the Chinese economy.

The role of government is pertinent to the flag and may be illustrated through a comparison of the response to air pollution in Beijing and in New Delhi. Currently, New Delhi has the distinction of ranking as the most polluted major city, with an air quality that is twenty-one times more than the WHO guideline. It is a virtual gas chamber. Every year has seen a worsening of air quality and its impact on the health of children and the elderly, without any credible steps to address the issue. Successive governments have lacked the political courage to take strong measures and win the confidence of the public, and have skilfully resorted to playing the blame-game card and indulging in ad-hoc, temporary jugaad-type measures. Beijing, like New Delhi, faced a similar situation over a decade ago, but the government’s response was markedly different. As it pursued rapid economic growth, the city witnessed a massive population surge and a rapid increase in vehicular traffic. Shrouded in smog, the city was among the most polluted till the government decided to act. Through a series of tough interventions, the government shut down heavy polluters, transitioned from coal to gas/electric vehicles, and invested hugely in public transport to cut down the use of private cars. Government policies were accompanied by strict monitoring, enforcement, public awareness, and implementation of public transport and other projects. In less than a decade, Beijing had improved its air quality by around eighty per cent.

In India’s case, the state needs to increasingly play three critical geopolitical roles in the innovation ecosystem. First, it needs to identify and signal its strategic priorities. Initiatives framed under Atmanirbharta (self-reliance), for instance, and national missions communicate where India seeks autonomy – whether in defence manufacturing, digital public infrastructure, clean energy or space. Second, the state needs to be an active participant and absorb early risk. In sectors where long gestation periods and high capital costs deter private investment, such as deep tech or defence, government funding and procurement will create entry points for domestic innovators and generate confidence. Third, the state should rewire its role and act as a platform builder and market creator. Public digital infrastructure and large-scale procurement shape entire markets, enabling Indian firms to scale domestically before competing globally.

Given the above context, for India to take advantage of its current growth trajectory and address the myriad developmental challenges it faces, it is its response to the innovation opportunity that would emerge as the tipping point. This would require unwavering political will and commitment that is not populist or temporary but cuts across party lines and engages the population in a joint collaborative endeavour. That India has innovators is a no-brainer. After all, during the COVID-19 pandemic, India emerged as the ‘pharmacy of the world’, and India is also the first country in the world to have landed a spacecraft on the dark side of the moon. Additionally, in the last year, Zoho Corporation, for instance, exemplified how private innovation aligns with national interests through strategic global expansion, bolstered by state incentives that enhance India’s tech sovereignty and economic edge in geopolitics. The state government of Tamil Nadu partnered with Zoho via initiatives like TANSTIA for MSME digitisation since 2019, while federal endorsements promoted Zoho’s office suite for digital self-reliance. Zoho sought $700 million in semiconductor incentives under India’s $10 billion chip scheme in 2024, signalling ‘Make in India’ validation.

The two critical sides of the innovation coin are funding and government support. To recognise that ideas must be monetised and the government to remain an enabler & support system is the foundation to weave innovation in the geostrategic tapestry. This requires building innovation into the national culture and psyche. For innovation to serve national interest, it must become a defining part of the nation’s cultural identity and not just confined to policy documents or start-up hubs. Nor indeed should the responsibility of innovation be left solely on the government’s shoulders. For this to happen, we need education that privileges curiosity and problem-solving, and not rote replication. Knowledge is not the accumulation of information but leveraging it to find better ways of doing things. Tolerance of failure and indeed, the active encouragement of trial-and-error, especially in high-risk, high-impact sectors, lie at the heart of an innovation culture. The very culture of being inquisitive and curious must begin in school. Collaboration and a national culture of innovation require that bridges be built between academia, industry, and government, enabling ideas to travel quickly from lab to market and, most importantly, leadership narratives that frame innovation as nation-building. Elite experimentation would, then, be reduced to a façade. As Alan Kay very gently put it, ‘the best way to predict the future is to invent it.’ For India, the strategic security of her future would be determined only through the strategic invention of it in consultation and collaboration with her people.

In a dramatically divisive and shifting geo-strategic landscape, India’s geopolitical aspirations of sitting at the high table and helping shape the Indo-Pacific architecture and championing the cause of the Global South will rest increasingly on its innovation capacity and its capability in finding solutions to the everyday problems people face. The very approach to innovation needs to be biographical. Economic quantum alone will not suffice; neither will diplomatic balancing. The decisive factor will be whether India can consistently translate talent into technology, ideas into institutions, and ambition into capability, and whether she does so collaboratively with her institutions and people. For India, as indeed for all developing economies, this is a strategic compulsion. It is the anchor of strategic autonomy, resilience, and global relevance. The nations that understand this will shape the emerging order and the future. India cannot afford to be anything but one of them.

Amit Dasgupta is a former Indian diplomat with an interest in management studies. Uma Sudhindra is a strategy consultant and a member of the Advisory Board at Strategic Research & Growth Foundation & Centre for National Security Studies. Views expressed are the author’s own.