- What began as ideological kinship evolved into an ecosystem: oil, gold, passports, logistics and political protection—often in open defiance of U.S. pressure.

- The Hezbollah in Venezuela is characterised as a potential terrorist group, but it has turned Venezuela into a hub of organised crime and international terrorism.

- Reports allege paramilitary camps on Margarita Island for ideological and militia training, where Hezbollah’s “Unit 910”, reportedly used Venezuela for intelligence and arms movement.

- The “parallel economy” includes gold and crypto, generating up to $1 billion yearly for Hezbollah globally, per DEA figures.

In the bustling streets of Caracas—where economic hardship and political fervour collide—a mural of Hassan Nasrallah, the late Hezbollah leader, stares back at passers-by like a statement of intent. Unveiled in late 2024 by local Lebanese and Palestinian communities, the artwork portrays Nasrallah flanked by Venezuelan and Lebanese flags, a tribute framed by its supporters as defiance against imperial power. Yet to others, it is a warning: global conflicts do not remain contained to their own geographies—they migrate, embed, and mutate.

That single wall painting captures more than symbolism. It reflects a relationship decades in the making—linking Iran, Venezuela, and Hezbollah through diplomacy, sanctions evasion, and contested underground networks. What began as ideological kinship evolved into an ecosystem: oil, gold, passports, logistics and political protection—often in open defiance of U.S. pressure. And even after Nicolás Maduro’s dramatic removal from power, the deeper question remains alive: can such networks be dismantled, or do they simply change hands?

Because this story isn’t only about statecraft. It is also about diaspora communities navigating divided loyalties, officials entangled in corruption, and ordinary citizens who pay the highest price whenever geopolitics turns a nation into a battleground.

Forging Bonds in the Face of Sanctions

The diplomatic ties between Iran and Venezuela trace back to the early 2000s, when Hugo Chávez, Venezuela’s Socialist leader, sought allies beyond the West. Chávez, elected in 1999, viewed Iran under President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as a kindred spirit in anti-imperialism. Both nations, rich in oil but targeted by U.S. sanctions, found common ground in the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). Both Venezuela and Iran were the founding members of OPEC. Their relationship deepened through energy cooperation: Iran helped refine Venezuela’s heavy crude, while Venezuela supported Iran’s nuclear ambitions diplomatically. As per reports, Venezuela is also the second highest importer of military equipment[1], including the Qods Aviation Industries (QAI) Mohajer-series of UAV’s, which had irked the US and got the Venezuelan company, “Empresa”, sanctioned for the deal.[2]

By 2005, Chávez’s visits to Tehran yielded over 300 agreements on manufacturing, energy, and agriculture. These weren’t mere handshakes; they were lifelines. As U.S. sanctions intensified, starting with visa bans on Venezuelan officials in 2006 and escalating under Obama, they pushed Caracas closer to Tehran. “We are all part of the axis of resistance,” Maduro once declared, in his visit to Iran[3].

Under Nicolás Maduro, who succeeded Chávez after his 2013 death, the bond solidified amid Venezuela’s economic collapse. Sanctions on PDVSA, Venezuela’s state oil company, crippled production. Iran stepped in with gasoline shipments in 2020 and a 20-year cooperation pact in 2022[4], including drone technology and refinery repairs. This “Anti-sanctions” alliance helped both evade U.S. restrictions, with Venezuela providing heavy crude and gold in return. Yet, it has incurred a cost: hyperinflation ravaged families, forcing millions to flee into US and Mexico.

Hezbollah’s Footprint: From Diaspora to Operations – Drugs, Laundering, and Trafficking

Hezbollah’s presence in Venezuela adds a layer of complexity. The Lebanese militant group, backed by Iran, has long leveraged global Shia diasporas for support. Venezuela’s Lebanese community provided fertile ground while corruption and weak governance were nourished. Under Chávez, Hezbollah sympathisers established networks, but Maduro’s regime allegedly offered a haven, turning the country into a hub for logistics and finance.

Hezbollah entered the Tri-border of Latin America and shifted to Venezuela as a fundraiser for its global activities, and such fundraising has key mechanisms, which include:

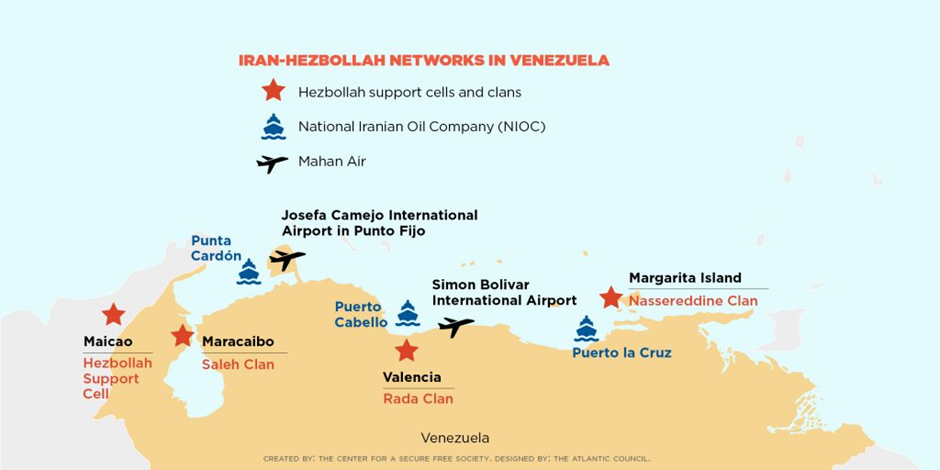

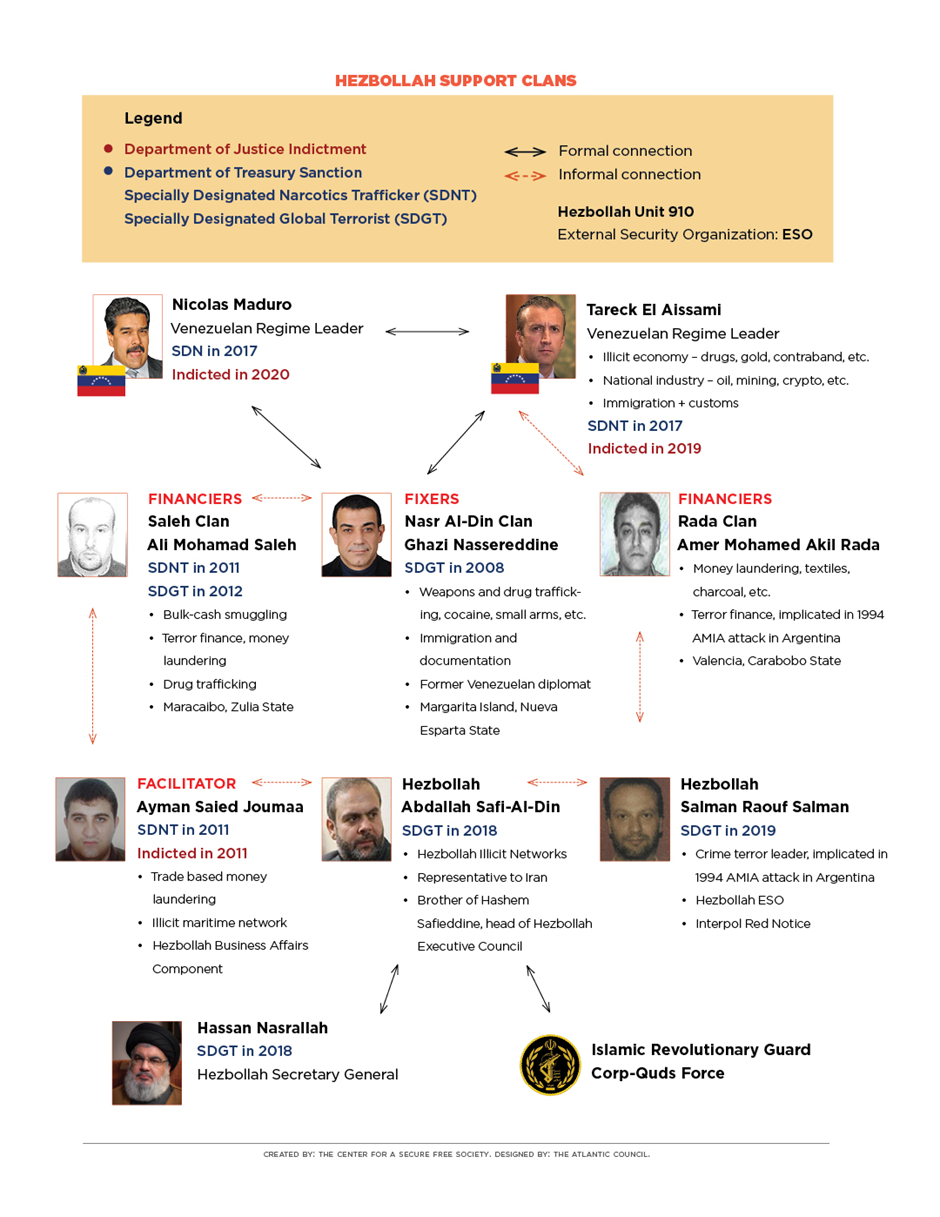

Financial Networks: Money laundering via gold mining in the Orinoco Arc and businesses on Margarita Island. Orinoco Mines are heavily exploited by Hezbollah and the local armed groups[5]. U.S. Treasury sanctions targeted figures like Ghazi Nasr al-Din, a Venezuelan diplomat accused of aiding Hezbollah’s fundraising[6] and facilitation of Hezbollah representatives in and out of Venezuela. Gold trade and shadow banking evade sanctions. Hezbollah clans reportedly embed in illicit economies, remitting funds to Lebanon.

Logistical Support: Venezuelan passports issued to Middle Eastern individuals over 10,000 between 2010 and 2019 granted visa-free access to 130 countries, facilitating global operations. Tareck El Aissami, Maduro’s former vice president of Lebanese-Syrian descent, was indicted by the U.S. for ties to drug lords and Hezbollah. He is accused of protecting the narcotics traffickers in Venezuela and the illicit movement of money[7], he was arrested in 2024.

Training and Ideology: Reports allege paramilitary camps on Margarita Island for ideological and militia training. Hezbollah’s “Unit 910”, a clandestine group of Hezbollah, reportedly used Venezuela for intelligence and arms movement.

U.S. authorities have long accused Hezbollah of using Venezuela for criminal enterprises to fund terrorism. The DEA estimates these activities generate tens to hundreds of millions annually, with Venezuela as a key node. Too often, the Hezbollah in Venezuela is characterised as a potential terrorist group, but it has turned Venezuela into a hub of organised crime and international terrorism.

Drug Smuggling: Hezbollah allegedly partners with Venezuelan cartels like the “Cartel of the Suns” (military-linked) and Colombia’s FARC dissidents. Cocaine routes shifted to Venezuela, with Hezbollah laundering proceeds. A 2020 U.S. indictment charged Maduro and allies with “narco-terrorism,” flooding the U.S. with cocaine.

Human Trafficking: Less substantiated, but reports link networks to smuggling people across borders, sometimes tied to drug ops. U.S. officials claim ties to U.S.-bound migration, though evidence is anecdotal.

Hezbollah and Venezuelan officials deny these claims, calling them U.S. propaganda. Iranian sources emphasise mutual aid against “imperialism.”

From Murals to Maduro’s Capture

Nasrallah’s murals, inaugurated post his 2024 death, symbolise ideological ties. In Caracas, they evoke solidarity with Palestine and Lebanon, but also highlight Hezbollah’s cultural influence. This culminated in Maduro’s dramatic U.S. capture on January 3, 2026, via a military raid. Secretary Marco Rubio cited Venezuela as a Hezbollah-Iran platform, threatening U.S. security. After the arrest of Madura, Rubio vowed a complete annihilation of Hezbollah operations from Venezuela in an interview.[8]

This alliance, born of shared adversity, has humanised resistance for some while fueling accusations of crime for others. As Venezuela transitions, the story underscores how sanctions can forge unlikely bonds, often at the expense of the vulnerable. Whether these ties fray or endure, they remind us: in geopolitics, the lines between ally and adversary blur, but the people endure.

Politically, Hezbollah’s role bolsters Maduro’s “axis of resistance,” aligning with Iran against U.S. “aggression.” Economically, it’s a survival strategy: Iran’s tech transfers (drones, refineries) sustain Venezuela’s oil sector, while Hezbollah’s networks provide revenue streams amid sanctions. This “parallel economy” includes gold and crypto, generating up to $1 billion yearly for Hezbollah globally, per DEA figures.

The U.S. aims to dismantle these networks, but experts warn ties may persist. “Hezbollah’s clans are resilient,” says Matthew Levitt of the Washington Institute. For Venezuelans, it’s a chance for renewal, though uncertainty looms. While President Trump wants to “run the country” and “fix the oil infrastructure”, will the common Venezuelan feel assured?

Maduro’s capture in early January 2026 has now transformed Venezuela from a sanctioned outlier into a geopolitical crime scene. For Washington, it is an opportunity to cut into what it alleges is an Iran–Hezbollah platform operating in the Western Hemisphere. For Caracas, it is a moment of dangerous transition—because removing a man is easier than dismantling the networks that flourished under him. In systems built on patronage, secrecy, and parallel economies, disruption often produces not closure, but fragmentation—new brokers, new routes, and new bargains.

The alliance that took shape between Tehran and Caracas was never just ideological. It was transactional survival: Iran gained strategic reach, Venezuela gained fuel, refinery support and drone technology, and Hezbollah-linked networks allegedly gained permissive terrain for financing and movement. This is the anatomy of modern sanctions-era geopolitics: pressure does not simply isolate states—it can reconfigure them, turning them into laboratories for bypass systems built on gold flows, shadow banking, document networks, and criminal partnerships. Even if one node collapses, the incentives that created the system rarely disappear overnight.

For ordinary Venezuelans, the promise of “renewal” will not be measured in speeches or arrests—it will be measured in electricity that stays on, inflation that stops devouring salaries, and the return of economic dignity without fear or retaliation. If the post-Maduro order becomes only a new stage for foreign power contests, the public will again be trapped between slogans and scarcity. Venezuela’s future will hinge on one brutal test: whether it can return to being a functioning state—or remain a corridor where geopolitics and organised crime simply replace one manager with another.

References:

- [1] https://www.wionews.com/photos/how-venezuela-and-houthis-became-key-recipients-of-iran-s-arms-exports-1768650180787/1768650180790

- [2] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sb0347

- [3] https://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2022/06/21/684261/Venezuelan-President-Nicolas-Maduro-Axis-Resistance-colonialism-hegemonic-powers

- [4] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/6/11/iran-venezuela-sign-20-year-cooperation-plan-during-maduro-visit

- [5] https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2019/01/14/-Hezbollah-exploiting-gold-mines-in-Venezuela-politician-reveals

- [6] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/hp1036

- [7] https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/as0005

- [8] https://www.foxnews.com/world/rubio-vows-eliminate-hezbollah-iran-operations-from-venezuela-after-maduro-capture

Sughosh Joshi is a CA Finalist and B.Com graduate with a strong interest in economics, geopolitics, and the analysis of international affairs, particularly those impacting India. Views expressed are the author’s own.