Jet Engines Decide Wars, and Dependence Is the Greatest Vulnerability in Modern Air Power

- Reliance on foreign sources for critical defence technologies is now a major strategic vulnerability amid shifting geopolitics, intensifying great-power rivalry, and the weaponisation of supply chains.

- Among all contemporary military systems, the jet engine remains the single most critical component.

- Perceived as a failure, the Kaveri programme in fact laid the foundation of India’s jet engine ecosystem—building core capabilities in single-crystal blades, FADEC, high-temperature superalloys, and comprehensive engine testing, including high-altitude trials.

- Jet engine sovereignty will demand roughly $12–15 billion over 15 years, with early-generation engines inevitably trailing global benchmarks—a necessary cost of building indigenous capability.

In the current security context, air power has emerged as the key component of modern warfare, frequently deciding a conflict’s result even before the ground forces completely participate. Control of the sky enables a country to strike deep, respond rapidly, protect critical assets, and impose strategic costs on an adversary with speed and precision. The fact that the side that establishes air superiority first gains a disproportionate advantage has been highlighted throughout history and in current conflicts, influencing the military and political outcomes of war.

However, the true strength of air power lies not merely in aircraft numbers, but in the technology that sustains and enables them. Dependence on other countries for vital defence technologies has become a significant strategic vulnerability in an era of shifting geopolitics, intensifying great-power competition, and weaponisation of global supply chains. As previously said, there are only everlasting national interests in international affairs, not everlasting allies or adversaries. External dependencies might result in supply interruptions, spare parts denials, operational limitations, or political pressure that directly compromises combat readiness during a crisis.

This is even more apparent in the air force, which has highly technological weaponry that cannot be substituted or replaced at short notice. Among all contemporary military systems, the jet engine remains the single most critical component. Without assured access to serviceable and continuously upgraded engines, a fighter aircraft ceases to be a reliable military asset and instead becomes an operational liability, even when sourced from long-standing partners.

Therefore, independence in defence technology is not a matter of prestige but of national survival. For a country seeking strategic autonomy and credible deterrence, sovereign control over critical technologies, most notably jet engine development, forms the cornerstone of air power, ensuring possession not only of aircraft platforms but also of the underlying technologies that sustain them.

The Kaveri Saga (1980s–Present): A Foundation Forged in Challenge

India’s foray into indigenous jet engine development began in 1986 with the initiation of the GTRE GTX-35VS “Kaveri,” a turbofan engine designed for the local “Light Combat Aircraft,” Tejas. This project was the country’s foray into the “crown jewel” of aerospace technology, designed to reduce its reliance on foreign engines supplied by Russia and the United States.

Technical Challenges & The Final Pivot: The Kaveri programme encountered the structural challenges common to first-generation engine developers, including limitations in high-temperature materials, immature precision manufacturing capabilities, and insufficient empirical testing experience. While the engine achieved an afterburning thrust of approximately 81 kN, it fell short of the thrust-to-weight ratio required for the Tejas’s operational performance envelope.

Contrary to the perception of a failure, the Kaveri series went on to become the backbone of jet engine technology development for the nation, providing key capabilities such as single-crystal blades for gas turbines, FADEC, high-temperature superalloy development, and comprehensive engine testing, including high-altitude trials.

Today, the heritage continues as the 46-49 kN class Dry Kaveri engine propels the stealth UCAV Ghatak, while the involvement of the private sector, headed by Godrej Aerospace, heralds a new beginning for a strong, independent jet engine development ecosystem for the nation.

The Current Portfolio: Building Capability Step-by-Step

| Program | Thrust / Power Class | Current Status | Strategic Role | Technical Significance |

| Kaveri (GTRE GTX-35VS) | 81 kN (with afterburner) | Technology demonstrator | Foundational R&D | Validated complete low-bypass turbofan architecture and core engine technologies |

| Dry Kaveri | 46–49 kN | UAV integration phase | Unmanned combat platforms (Ghatak) | Adapts fighter-grade engine technology for stealth UCAV applications |

| HTFE-25 | 25 kN | Certification phase | Trainers & medium UAVs | India’s first production-intent indigenous turbofan engine |

| HTSE-1200 | 1200 shp | Prototype testing | Utility & light helicopters | Expands indigenous aero-propulsion capability beyond fixed-wing platforms |

| AMCA Engine (Future) | 110–130 kN | Co-development stage | 5th-generation air dominance | Ultimate test of strategic sovereignty in high-performance combat propulsion |

Metallurgy & the Broader Challenge: Why India Struggles with Fighter Jet Engines

The development of a world-class engine in the indigenous fighter jet is no one-off challenge but a whole system of interconnected challenges. The key area in this system is the science of high-performance materials, and that is itself a difficult frontier.

Metallurgical Challenges

Today’s engines encounter a turbine temperature of 1,700°C and above. This is quite high for nickel superalloys, which melt at only around 1,400°C. The key is high-performance single-crystal superalloys, ceramic matrix composites, and thermal barrier coatings.

| Component | Material Challenge | Why It’s Hard |

| Turbine blades | Nickel-based SX alloys (CMSX-4, René N6) | Defect-free crystal growth, expensive rhenium, directional solidification |

| Vanes & nozzles | SX alloys + SiC/SiC CMCs | Avoid micro-cracks, perfect fibre-matrix interface |

| Combustor liner | Cobalt alloys + CMCs | Steep thermal gradients, creep buckling |

| Compressor & fan | Titanium alloys, CFRP hybrids | Fire risk, alpha-case, bonding dissimilar materials |

| Shafts & discs | PM nickel alloys | Grain boundary engineering, defect-free consolidation |

| Casings | Titanium & nickel | Residual stress management from complex machining |

Enabling technologies such as thermal barrier coatings (TBCs), advanced internal cooling architectures, hot isostatic pressing (HIP), and additive manufacturing require decades of accumulated institutional expertise and iterative refinement. Geopolitical constraints further complicate access to critical inputs, including rhenium, cobalt, high-purity titanium, and yttrium, rendering aerospace supply chains strategically sensitive and inherently vulnerable.

Systemic Technical & Programmatic Bottlenecks

| Category | Challenge | Impact |

| Design & R&D | Absence of validated design tools, limited empirical datasets, and immature materials science | Repeated test failures; short engine service life |

| Manufacturing | Inconsistent tolerances, weak investment casting capability, and limited blisk machining maturity | High scrap rates, poor subsystem integration, reduced durability |

| Systems & Integration | Underdeveloped FADEC, sensors, thrust vectoring | Sub-optimal control, poor throttle response |

| Program Structure | GTRE lab mindset, no prime integrator, stop-go funding | Products not certifiable, accountability diffused, chronic delays |

| Ecosystem | Weak SME base, limited test facilities, talent drain | Reliance on imports, slow progress, and lost tribal knowledge |

| Strategic | Fragmented ownership, isolation from global R&D | Missed learning, repeated underestimation of complexity |

The Geopolitical & Supply Chain Trap

India remains caught in a self-reinforcing cycle in indigenous fighter jet engine development. Immediate operational requirements necessitate engine imports, which in turn reduce institutional urgency and resource prioritisation for domestic programmes.

Geopolitical hurdles add to these concerns. International regimes, including MTCR, ITAR, and the Wassenaar Arrangement, deny developing countries necessary access to important technologies such as hot-section hardware, FADEC, and advanced superalloys. Even in joint projects, such as the GE-F414 engine or the Safran joint venture, the design authority, enhancements, and exports remain primarily with established firms.

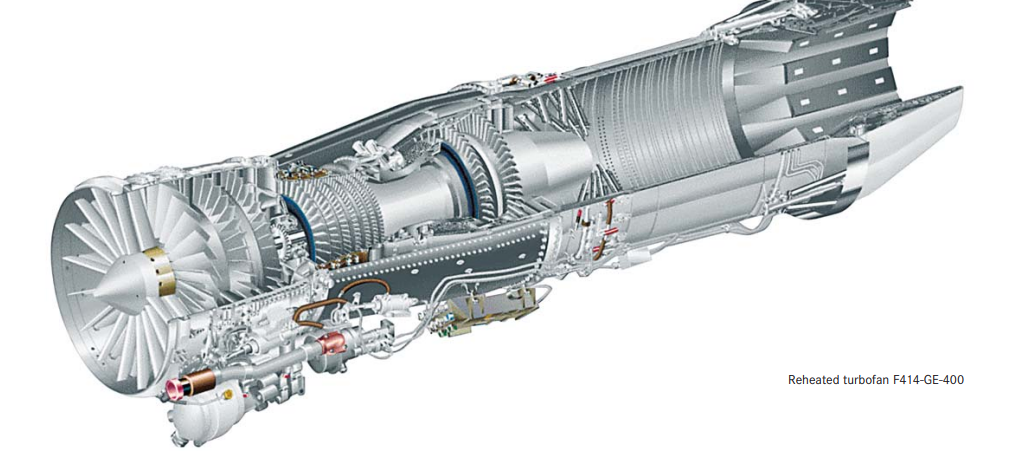

Performance specifications (sea level/standard day) F414-GE-400 Max. thrust, reheated 22,000 lbf 98 kN Length 154 in 3,912 mm Air flow rate 170 lbs/s 77.1 kg/s Maximum diameter 35 in 889 mm Inlet diameter 32 in 810 mm Pressure ratio 30:1 30:1 Thrust-to-weight ratio 9:1 9:1

As a result, India’s supply-chain exposure is particularly acute. The country imports nearly all of its rhenium, cobalt, yttrium, and aerospace-grade titanium, while key manufacturing infrastructure, including directional solidification furnaces, electron-beam physical vapour deposition (EB-PVD) systems, and high-precision five-axis CNC machines, continues to be sourced largely from overseas suppliers.

Institutional constraints further impede progress. GTRE operates primarily as a research laboratory with a risk-averse culture; HAL functions largely as a license-production agency with limited design authority; and annual, fragmented budget cycles prevent sustained iterative development and learning.

Addressing these limitations will require a deliberate institutional reset rather than incremental reform. Only a clearly mandated National Propulsion Mission Authority, led by the private sector, anchored in assured long-term funding, and integrated with critical materials acquisition, indigenous tooling development, and carefully structured global partnerships, can break the existing cycle of dependence. Achieving engine sovereignty will necessitate a long-term commitment of approximately 15 years, investment in the range of $12–15 billion, acceptance of early-generation performance shortfalls, and fundamental changes in organisational structure and programme management.

The “Manhattan Project” Alternative for Jet Engine Sovereignty

The most acute vulnerability in India’s defence architecture lies not in aircraft platforms or missile systems, but in aero-engine capability. Limited progress over decades reflects institutional shortcomings rather than purely technical failure, with fragmented ownership, risk aversion, and programme discontinuity constraining outcomes. Mission-mode governance models used successfully in the United States offer a relevant reference point for institutional reform.

The proposed National Propulsion Mission Authority (NPMA) adopts a Manhattan Project-style approach, operating directly under the Prime Minister’s Office, supported by assured multi-year funding, private-sector leadership, and global talent access with minimal procedural constraints. Failure is treated as an intrinsic component of accelerated learning, with the explicit objective of delivering combat-ready engines rather than laboratory demonstrators.

NPMA replaces risk-averse, lab-based product development policies with privatisation of implementation, long-term funding, world-class sourcing, and professional management. Instead of an optimal technique, NPMA emphasises feasible application.

This plan begins with securing access to critical raw materials, including rhenium, titanium, and high-performance alloys and progressively transitions toward domestic production enabled by additive manufacturing, rigorous quality control, and process validation. Over the longer term, India aims to advance toward next-generation materials, AI-assisted design methodologies, and future propulsion architectures.

Geopolitical constraints are mitigated through diversified strategic collaborations with the United States, France, Russia, Israel, and Japan, while simultaneously pursuing a non-aligned engine development framework involving partners facing comparable dependency constraints. Achieving jet engine sovereignty will require an estimated investment of $12–15 billion over approximately 15 years, with initial-generation engines expected to underperform established global benchmarks, a trade-off inherent to first-time capability development.

Jet engines are not acquired during wartime. Jet engines need to be produced during peacetime. It is not about saving dollars but about having freedom. The time has come for India to overcome bureaucratic stagnation. Otherwise, it has to remain in bondage.

India’s Jet Engine Sovereignty: Strategic Roadmap

| Phase | Key Focus | Timeline | Success Driver |

| Strategic Realisation | Declare jet engines a national security priority | 2024 | Political & military consensus |

| Institutional Break | Create NPMA with PMO control and 10-year funding | 2024–25 | Statutory autonomy |

| Execution Shift | Private prime, DRDO support, global leadership | 2025–26 | Commercial accountability |

| Parallel Development | Multiple engine cores, fail-fast testing | 2026–30 | Learning through iteration |

| Supply Chain Security | Critical minerals, titanium, stockpiles | 2025–28 | Material sovereignty |

| Manufacturing Control | Indigenous equipment, additive manufacturing | 2028–32 | Process independence |

| Geopolitical Balance | Multi-aligned & non-aligned partnerships | 2026–34 | Technology access |

| Performance Acceptance | Accept Gen-1 performance gap | 2030–33 | Political courage |

| Operational Integration | Flight tests and AMCA Mk-2 induction | 2034–38 | IAF confidence |

| End State | Indigenous production-certified engine | 2038 | Export & next-gen R&D |

| Category | Estimated Cost / Return | Timeframe |

| Total Program Cost | ~$15 billion | 2024–2038 |

| Average Annual Investment | ~$1 billion | Sustained |

| Break-even Point | Cost recovery begins | 2038–2040 |

| Long-Term Return | $50+ billion (imports avoided + exports) | By 2050 |

NPMA Engine Performance Targets

| Metric | Target | Acceptable Minimum (First-Gen) |

| Thrust | 110–130 kN | ≥105 kN |

| Thrust-to-Weight Ratio | 9:1 | ≥7.8:1 |

| Time Between Overhaul (TBO) | 4,000 hours | ≥1,200 hours |

| Indigenous Content | ≥90% | ≥70% |

| Unit Cost | Comparable to imports | Up to +40% |

Piyush Anand is a Biotechnology Engineering student at Chandigarh University. His primary interest lies in International Affairs, Defence and Strategy. Views expressed are the author’s own.