- Tehran is accused of harassing shipping and using proxy networks, actions the US and its allies view as key elements of Iran’s coercive strategy.

- Iran seeks assurances against rapid military action and prolonged isolation, while US policymakers demand verifiable limits on enrichment before easing pressure.

- The combination of military pressure and mediated diplomacy is not coincidental: coercion is intended to build leverage at the bargaining table.

- Unmanned weapons, carrier groups near choke points, and Iran’s internal tensions increase the risk that a minor incident escalates before talks can begin.

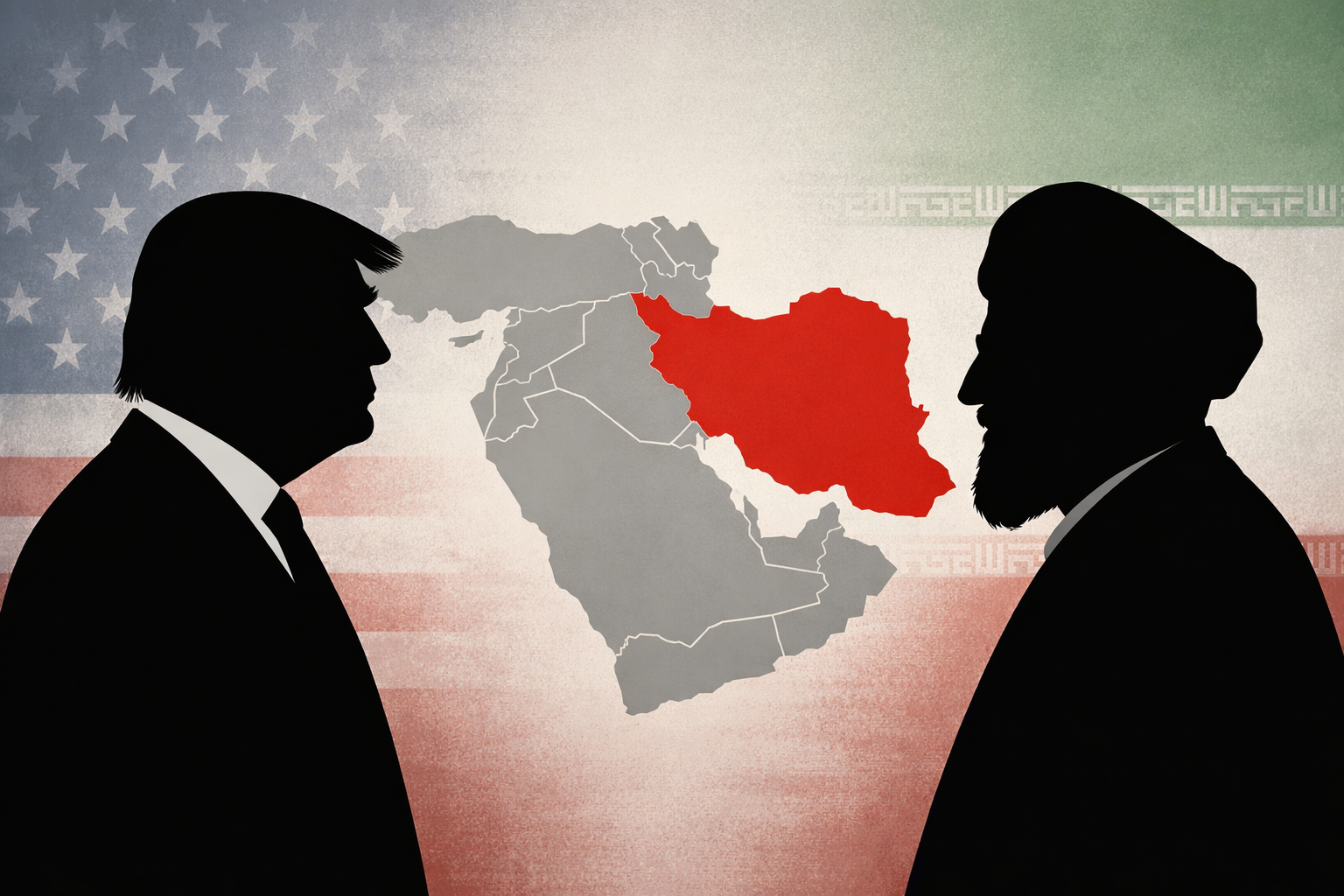

The first few weeks of 2026 have made West Asia tense again. A series of maritime confrontations, aerial encounters, and increasingly public diplomatic maneuvers have led to a fragile mix of pressure and outreach. This is a classic security dilemma in which actions taken to make one side feel more secure make the other side feel more vulnerable. Three connected outcomes are at stake: whether coercive pressure leads to a real return to talks, whether local and proxy flashpoints are kept under control, and whether an accident or mistake leads to a bigger military spiral. The signs right now are not good.

The catalytic events are well-known: US naval and air assets operating in the Arabian Sea and wider Gulf region have encountered Iranian drones, fast boats, and other platforms; most recently, a US fighter shot down an Iranian Shahed-139 drone as it approached the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (aircraft carrier), an incident Washington described as self-defence. At the same time, Tehran has been accused of harassing commercial shipping in the Strait of Hormuz and using asymmetric tools through a network of proxies, actions that the US and many of its allies regard as part of Iran’s coercive toolset. These operational dynamics occurred with a dramatic domestic picture in Iran: enormous protests and a ruthless security reaction that have damaged Tehran’s internal cohesion while complicating its external position.

What makes this different from other regional fights? The current stalemate is more dangerous than many short-lived conflicts from the past ten years because of two major changes. The weapon set has grown and changed in a number of ways. Cheap but effective loitering weapons, improved stocks of ballistic and cruise missiles, and the regular use of small boats to harass have made it easier for people to get into fights at sea and in the air. If an unmanned system takes the wrong approach, a crewed fighter on an aircraft carrier group can immediately take defensive action. This is what happened last week when the plane was shot down. This dynamic makes decisions take less time and makes it more likely that tactical self-defence will be seen as strategic provocation.

Second, the world is very divided right now. Israel‘s hostile stance toward Iran’s nuclear and regional footprint, the fallout from the fighting in Gaza, and the competition among Gulf states for power all create many ways for local crises to spread. Domestic political signalling makes things harder for Washington: public talk about deterrence, visible changes in military posture, and tightly planned pressure campaigns all limit Tehran’s options for responding, which could make it harder to find a way out of the situation that would have been possible if things were calmer.

Diplomacy Is Precarious, Contentious, And Conditional

Despite the energetic friction, there are genuine diplomatic strands. Masoud Pezeshkian, Tehran’s new president, has directed diplomats to conduct “fair and equitable” negotiations with the United States, while Washington has not ruled out a resumption of talks. Mediators and regional capitals, including Turkey, Oman, and Qatar, are quietly offering platforms and back-channel space. That combination—military pressure combined with mediated diplomacy—is not coincidental: coercion is intended to build leverage at the bargaining table. However, leverage that is regarded as punishing can be counterproductive if it hardens the opposing side’s red lines or encourages asymmetric reprisal through proxies.

Two things make current diplomacy weak.

First, there is a disagreement over the format. Tehran is said to prefer bilateral talks held in Oman, while Washington, aware of its allies’ concerns, has shown interest in broader, possibly multilateral, processes that include regional stakeholders. Second, there is still a lot of disagreement about sequencing and verification. Iran wants to know that talks won’t be followed by quick military action or long periods of isolation. US policymakers want real limits on enrichment and measures to make things more open before they ease economic and political pressure. Without a reliable way to sequence things, like a progressive verification plan with guarantees from a third party, meetings could end up making carefully worded statements instead of results that can be enforced.

The Dangers Are Not The Same On The Ground

Even if the governments in Tehran and Washington want things to calm down, the people who work in the area have their own ideas about how things should be done. Iranian Revolutionary Guard units, Quds Force proxies in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen, and non-state marine actors are all strategically placed to throw off the enemy’s plans and keep Tehran’s exposure to a minimum. On the other hand, US force packages, which include carrier strike groups, missile defences, and long-range strike capabilities, are meant to calm partners and stop things from getting worse. These asymmetric tools create several points of friction, such as misinterpreted radar tracks, an intercepted commercial ship, or a proxy attack that causes the US to respond in a measured way. In these situations, third parties like Israel and Saudi Arabia may take unilateral actions that make the crisis worse.

For countries such as India, the stakes are both practical and strategic. Disruption of shipping in the Arabian Sea increases energy security costs and supply chain risks. Political unrest in Iran threatens refugee flows and an increase in regional humanitarian needs. More broadly, a persistent regional crisis consumes diplomatic bandwidth and accelerates security-focused weapons dynamics throughout Asia, disrupting partnerships and trade relations at a time when economic resilience is critical. New Delhi’s favoured strategy—calibrated diplomacy and diversification of energy and strategic connections—remains relevant in this context. At the same time, India must hedge operationally against marine and energy risks.

Conclusion: A Small Chance, But No Promises

The current mix of war and diplomacy makes it possible to reach a stable, negotiated end in a short amount of time. But the window isn’t stable. The use of unmanned systems as weapons, the closeness of carrier groups to controversial choke points, and the domestic tension that is splitting Iranian policymaking all make it more likely that a small incident will get worse before negotiations can begin. To make an off-ramp, careful, technically sound diplomacy will be needed that includes the hard math of sequencing and verification, as well as strict operational restraint on all sides. If diplomacy fails, there will be serious problems for the area, the world economy, and security.

Anusreeta Dutta is a columnist and climate researcher with experience in political analysis, ESG research, and energy policy. Views expressed are the author’s own.