- Even after China and Japan normalised diplomatic relations in 1972, the question of justice and reparations for Chinese victims—especially comfort women and survivors of massacres, which mainly remains unsolved.

- Although important concerns like individual claims by comfort women and forced labourers remained unresolved, the “1978 Treaty of Peace and Friendship” strengthened promises of non-aggression and added a strategic anti-hegemony clause targeting Soviet influence.

- Long-lasting tensions between the two nations have been exacerbated by the absence of complete reparations or a formal apology comparable to ‘Germany’s post-Holocaust model of restitution’.

- Recent court decisions in Tokyo in 2024 that granted damages to Chinese forced labourers are one example of how legal advances have heightened tensions.

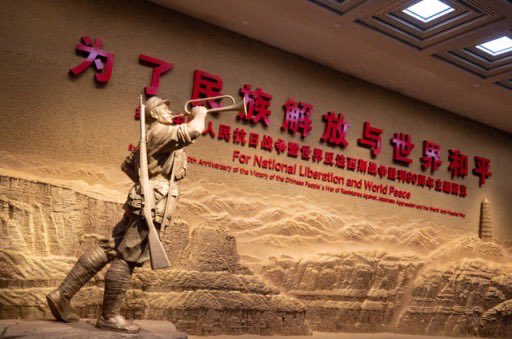

The 88th anniversary of China’s all-nation resistance to Japanese imperialism, a pillar of Chinese national identity and historical consciousness, was celebrated on July 7, 2025. President Xi Jinping’s monument in Monument Square, which honoured the martyrs of the Hundred-Regiment Campaign—a massive military offensive against Japanese forces invading northern China in 1940 by the Communist Eighth Route Army—was the focal point of the remembrance. Six hundred people attended the ceremony, including descendants of resistance fighters and veterans of the conflict. One of them, war veteran Liu Zhirong, urged people to remember the trauma of the country, oppose historical revisionism, and forcefully remind those present that “the crimes committed by Japanese invaders are too numerous to be recorded.”

The celebration commemorates the anniversary of the July 7, 1937, “Lugou Bridge Incident,” sometimes called the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident,” which is generally considered to have been the catalyst for the “Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)”. That night, a small-scale military conflict turned into a full-fledged conflict that continued until the end of World War II. Japan’s military strategy included extensive crimes like the “Nanjing Massacre”, “chemical warfare”, “forced labour”, and “sexual enslavement”, and its imperialist aspirations resulted in the conquest of large areas of China. Over 35 million people, including troops and civilians, are thought to have died during the conflict, according to Chinese estimates, and this number continues to influence China’s legal and diplomatic stance toward Japan. One of the most significant resistance operations conducted by the Chinese Communist troops against the Japanese invaders is the Hundred-Regiment Campaign, which will be honoured at the 2025 celebration. It represents both military defiance and the collective desire of a people for sovereignty.

China’s strategic use of historical memory as a tool for international policy and as a domestic unifier is shown in President Xi’s attendance and speech at the ceremony. State-led remembrance has been framed in recent years, particularly under Xi’s leadership, as part of a narrative of “national rejuvenation” that links historical humiliation with modern might. This ceremony is intended to reaffirm state legitimacy, national unity, and the Communist Party’s historical duty, in addition to being a time for grieving the past. Leaders discreetly handle contemporary geopolitical difficulties by bringing up the memory of the war and resistance, especially in the Asia-Pacific area, where disagreements over historical interpretation, territorial claims, and security alliances are still being fought.

Even by the standards that were in vogue in the early 20th century, Japan’s actions during the war in China constitute a blatant breach of specific “International Humanitarian Law” criteria. “The Nanjing Massacre (1937)”, in which tens of thousands of women were raped and an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 civilians were massacred, was one of the major infractions. Another was the use of chemical and biological weapons against the Geneva Protocol of 1925. The creation of “comfort stations,” where an estimated 200,000 Asian women where many of them being Chinese, were forced into prostitution. Under contemporary frameworks like the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998), which codifies genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, these acts are acknowledged as war crimes and crimes against humanity. The concept of universal jurisdiction, which allows states to pursue some serious crimes regardless of where they were committed, retroactively addresses these crimes even though the ICC did not yet exist. “The International Military Tribunal for the Far East” (IMTFE), also famously known as the “Tokyo Trials”, was founded in 1946 to try Japanese officials for crimes of war and aggression after Japan’s surrender in World War II.

However, because many of the atrocity perpetrators in China received light penalties or were never tried at all, the tribunal has come under fire for its selective justice. The “Tokyo Trials” prioritised crimes against Western prisoners over atrocities against Asian citizens, according to critics including historian Yuma Totani and legal expert Richard Minear. Even after China and Japan normalised diplomatic relations in 1972, the question of justice and reparations for Chinese victims—especially comfort women and survivors of massacres, which mainly remains unsolved. China waived state-level war reparations in exchange for economic cooperation, and Japan recognised the People’s Republic of China as the only legal government. The 1972 Sino-Japanese Joint Communiqué marked a turning point in bilateral relations. With the help of Japan’s Official Development Assistance, which greatly aided China’s modernisation efforts during the ensuing “golden decade” of cooperation from 1972 to 1992, trade increased dramatically from about $1 billion in 1972 to $317 billion by 2010.

Although important concerns like individual claims by comfort women and forced labourers remained unresolved, the “1978 Treaty of Peace and Friendship” strengthened promises of non-aggression and added a strategic anti-hegemony clause targeting Soviet influence. Recent court decisions in Tokyo in 2024 that granted damages to Chinese forced labourers are one example of how legal advances have heightened tensions. Japan has appealed this decision, claiming that “sovereign immunity” and the “1972 communiqué” resolved such claims.

While Japan’s strategic alliance against Communist China and the USSR was anchored by the “U.S.-Japan Security Treaty of 1960”, the historic visit of U.S. President Nixon to China in 1972 sparked “Sino-Japanese normalisation” as part of Cold War realignment strategies, and this changing legal landscape is part of a larger global context. In addition to its absence from the “1951 San Francisco Treaty”, the Cold War and its aftermath caused China to remain diplomatically isolated until normalisation. Notwithstanding this complicated past, economic relations thrived, with Japan’s assistance directly supporting China’s reform and opening-up initiatives. But difficulties remained as old complaints returned, particularly the unresolved individual wartime claims that still come up in legal and political discussions. As a result, even as both nations participate pragmatically in regional and international institutions, the slow shift from postwar isolation to profound economic cooperation and strategic diplomacy has been dotted by legal and historical conflicts that continue to be delicate in bilateral relations.

The 1930s and 1940s saw the widespread acceptance of some ideas under customary international law, including the prohibition of torture, the non-derogability of war crimes, and the protection of civilians during times of conflict. As a result, Japan’s conduct in China might be viewed as both a historical wrong and a legal transgression of the binding standards of the time. Furthermore, these legal precepts still serve as the foundation for China’s demands for an apology and recognition. Long-lasting tensions between the two nations have been exacerbated by the absence of complete reparations or a formal apology comparable to “Germany’s post-Holocaust model of restitution”. Japan’s previous expressions of regret, including the “2015 Kono Statement and the 1995 Murayama Statement”, have been perceived by many in China as inadequate or lacking sincerity, especially when accompanied by behaviours that contradict one another, such as political visits to the “Yasukuni Shrine”, which commemorates war criminals who have been found guilty. The legal battle for acknowledgement of the atrocities has fuelled a broader conversation in China about “national humiliation” (guochi), a notion ingrained in Chinese diplomacy, education, and even the preamble of the Constitution, which alludes to the Communist Party’s historic mission to put an end to China’s century-long humiliation. This collective memory has two purposes- it is a source of solidarity and a moral-legal claim to justice and respect on a global scale.

A key “anti-hegemony phrase”, intended as a mutual commitment to oppose dominance by any superpower, was included in the “1978 Treaty of Peace and Friendship”, which was signed to formally normalise diplomatic relations between the US and the USSR. Deeper problems remained unaddressed, especially those related to historical memory and territorial claims, even as economic connections flourished and Japan offered China official development assistance. “The Japanese textbook debate of 1982 rekindled long-standing hostility”. Following media claims that new Japanese textbooks have downplayed or whitewashed portrayals of wartime atrocities, Chinese protests broke out. According to research, Beijing used this episode to “mobilise nationalists” at home and to exert pressure internationally, reorienting the discourse away from communist ideology and toward a more cohesive narrative of victimisation and humiliation of the country. China broadened its “Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law in 2025” to target foreign companies, particularly Japanese ones, who are alleged to have “denied” historical horrors like the “Nanjing Massacre”. By imposing financial and reputational penalties on businesses deemed to be questioning China’s historical narrative or adhering to anti-China sanctions imposed by other countries, this law has intensified tensions. Japanese companies in particular have had to balance the danger of sanctions enforcement by the US or EU with Chinese sensitivities.

Since 2007, “China’s Belt and Road Initiative” has been increasingly thwarted by Japan’s growing alignment with the U.S.-led Quad (Japan, U.S., Australia, and India). As a reflection of Japan’s transition from postwar pacifism to more assertive regional security, Tokyo views the Quad as both a security alliance and a check on China’s expanding influence in Asia and the Pacific, particularly in maritime security. Regional diplomatic alliances, investment flows, and infrastructure competition have all been impacted by the “Belt and Road rivalry”. The strategic rivalry has intensified as a result of Japan’s engagement with “ASEAN nations” and its backing for “high-quality” alternatives to Chinese infrastructure funding. With all three facing U.S. tariffs and changing global supply chains, the first China-Japan-South Korea summit in years in March 2025 showed renewed enthusiasm for trilateral free trade discussions and tight regional economic cooperation. Trade ministers decided to expedite talks on a direct “free trade agreement (FTA)” between the three powers and work together to advance the “Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership’s (RCEP) implementation.

Seoul played down the unity story, claiming that the focus of consensus was on dialogue, while Beijing hailed this as a united front against U.S. tariffs. Asian trade integration both competes with and protects the trilateral process, which is still cautious but practical. In the 1990s, cooperation flourished as commerce and diplomatic exchanges grew rapidly.

However, tensions increased throughout the 2010s, especially after Japan nationalised the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in 2012. A 5% yearly decline in trade, a rise in security deployments, and long-term tensions over sovereignty and resource rights resulted from the sharp increase in Chinese maritime patrols and the large anti-Japan riots that followed. Both parties hardened their stances, upending the tacit agreement to “shelve” the territorial dispute from the “Deng Xiaoping era”. Beijing viewed the nationalisation as a push for sovereignty and was unimpressed by Japanese claims that it was a measure to prevent hardline local actions. Recent 2025 negotiations under PM Ishiba produced practical collaboration despite ongoing disagreements, such as growing tensions over Taiwan, more maritime encounters, and ongoing mistrust between the two countries. Fisheries agreements were signed to control competition for resources and steer clear of hot spots close to disputed areas, indicating a desire to keep lines of communication open and compartmentalise tensions. The Ishiba administration has struck a balance between maintaining hardline elements in Japanese politics that closely monitor developments in cross-strait (Taiwan) relations and domestic public sentiment, where mistrust of Beijing is still high, and overtures for better ties—hosting summits, indicating openness for dialogue.

To guarantee the preservation of these historical facts, China has also implemented several domestic legal reforms and scholarly initiatives, such as “The Memorial Law” (proposed), which mandates public education on war atrocities. And “The State Archives Administration” digitises historical archives- “comfort women” museums and survivor testimonial databases have been established. International organisations, such as UNESCO, have contributed to preserving war-related historical sites and memories in recent decades. The politicisation of historical memory in international law forums was once again brought to light when Japan opposed China’s request to add the “Nanjing Massacre” materials to the “UNESCO” “Memory of the World” Register.

China has also worked with other countries, such as South Korea, where campaigns focused on comfort women have resulted in public memorials and international lawsuits. These partnerships support China’s contention that its demands are motivated by “universal ideals of justice, truth, and compensation rather than nationalism”. Bilaterally, the 2008 China-Japan cultural exchange agreements facilitated joint history research, though disputes over Nanjing’s death toll stalled progress. Legally, a 2025 memorandum proposed joint history education to counter revisionism, pending ratification. Globally, “China’s 2024 UNESCO Nanjing archive submission”, backed by ASEAN”, faced Japan’s objections, highlighting competing narratives. “The 2025 China-Japan-South Korea trilateral summit emphasized cultural dialogue, balancing U.S.-Japan security ties” (e.g., 2024 Taiwan Strait drills). Historically, bilateral ties saw cultural cooperation peak in the 2000s, but post-2012 Senkaku tensions shifted focus to digital memory, with China’s 2025 “Memory of Nanjing” platform archiving survivor testimonies, gaining global traction despite Japan’s protests.

The 88th anniversary of China’s defence against Japanese aggression serves as a potent reminder of moral justice, historical tenacity, and continuous remembrance. China highlights a global need for historical truth, fairness, and accountability in addition to national pride by establishing this recollection in legal and moral imperatives frameworks. Ceremonies like this, supported by archival data and legal rationale, act as a caution to the future and a safeguard against forgetting in a world when historical revisionism and denialism are on the rise.

References:

- Anadolu Agency. (2025, July 7). China marks the 88th anniversary of the Japanese war. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/china-marks-88th-anniversary-of-japanese-war/3624262

- China Daily Hong Kong. (2025, July 8). Xi pays tribute to martyrs in the resistance war against Japanese aggression. https://www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/615406

- China Daily Hong Kong. (2025, July 9). The 100-regiment campaign in the resistance war marked in Shanxi. https://www.chinadailyhk.com/hk/article/615875

- CGTN via PR Newswire. (2025, July 9). CGTN: Why does China honour the spirit of resisting aggression? https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cgtn-why-does-china-honor-the-spirit-of-resisting-aggression-302500931.html

- State Council Information Office of the PRC. (2025, July 11). Bearing history in mind for a better future: A message from China on the resistance war anniversary. http://english.scio.gov.cn/m/topnews/2025-07/11/content_117973765.html

- Xinhua News Agency. (2025, July 8). Xi Jinping commemorates war martyrs at the Shanxi memorial. http://english.www.gov.cn/news/topnews/202507/08/content_WS668bdcd7c6d0868f4e8e72f7.html

- Permanent Mission of Norway to the UN and WTO/EFTA in Geneva. (2021, June 14). Interactive dialogue with the Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic [Statement]. 47th Session of the UN Human Rights Council. https://www.norway.no/en/missions/wto-un/nig/statements/hr/hrc/hrc47/hrc47hrc47—nb8–idcoisyria/

- The Sunday Diplomat. (2025, January 15). Justice beyond borders: The Nuremberg Trials and prosecution for modern war crimes. Retrieved July 16, 2025, from https://thesundaydiplomat.com/justice-beyond-borders-the-nuremberg-trials-and-prosecution-for-modern-war-crimes/

- Avery, C., & Holmlund, M. (Eds.). (2010). Better off forgetting?: Essays on archives, public policy, and collective memory (Illustrated ed.). University of Toronto Press. https://dokumen.pub/better-off-forgetting-essays-on-archives-public-policy-and-collective-memory-1442641673-9781442641679.html

- United Nations. (1978). Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Japan and the People’s Republic of China. United Nations Treaty Series, 1225, 207–214. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201225/volume-1225-I-19784-English.pdf

- China Briefing. (2025, March 25). New guidelines for implementing China’s Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law: What foreign companies need to know. https://www.china-briefing.com/news/new-guidelines-for-implementing-chinas-anti-foreign-sanctions-law-what-foreign-companies-need-to-know/

- Chambers and Partners. (2025). Sanctions 2025: China—Trends and developments. In Chambers Global Practice Guides. https://practiceguides.chambers.com/practice-guides/sanctions-2025/china/trends-and-developments

- Medcalf, R. (2020). The U.S.–Japan–India–Australia Quadrilateral Security Dialogue: A nascent balancing coalition in the Indo-Pacific? Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA). https://fiia.fi/en/publication/the-us-japan-india-australia-quadrilateral-security-dialogue

- Sundararaman, S. (2022). The Quad and balancing China since 2007: A theoretical assessment. Strategic Analysis, 46(6), 535–551. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9734955/

- Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan. (2025, March 30). Joint media statement of the trilateral summit between China, Japan, and South Korea. https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2024/03/20250330001/20250330001-a.pdf

Dr. Lakshmi Karlekar is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Humanities – Political Science and International Relations, Ramaiah College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Bengaluru. She holds a PhD in International Studies from CHRIST (Deemed to be) University. Tanishaa Pandey is a BBA LLB student at the School of Law, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Central Campus, Bengaluru. Views expressed are the author’s own.