A Data-Driven Analysis of Five Years of Chronic Pollution (2020-2025)

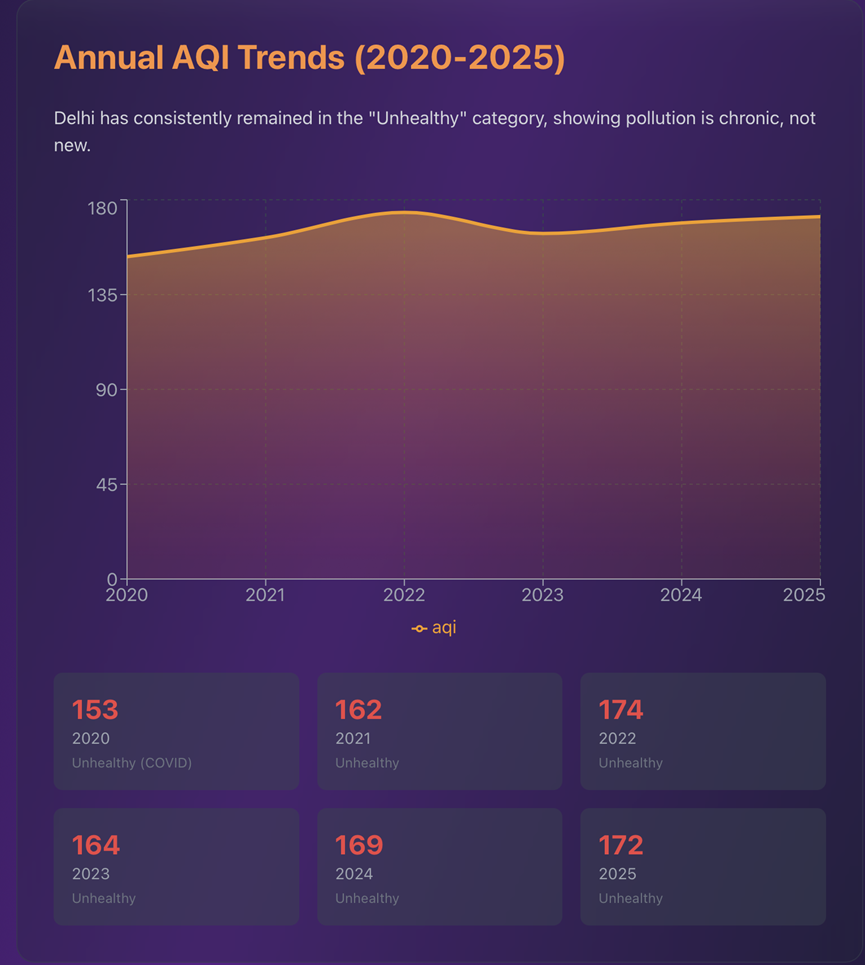

- The air quality index (AQI) yearly average score between 2020 to 2025 has consistently demonstrated that air quality in India was not to be interpreted as a temporary ‘pollution emergency,’ but instead a long-term, systemic failure with a sustained, low-grade pollution problem.

- The data does not demonstrate a crisis occurring abruptly, but rather an extended, incremental issue that has finally culminated in the systemic collapse of air quality within and around the entire Delhi region.

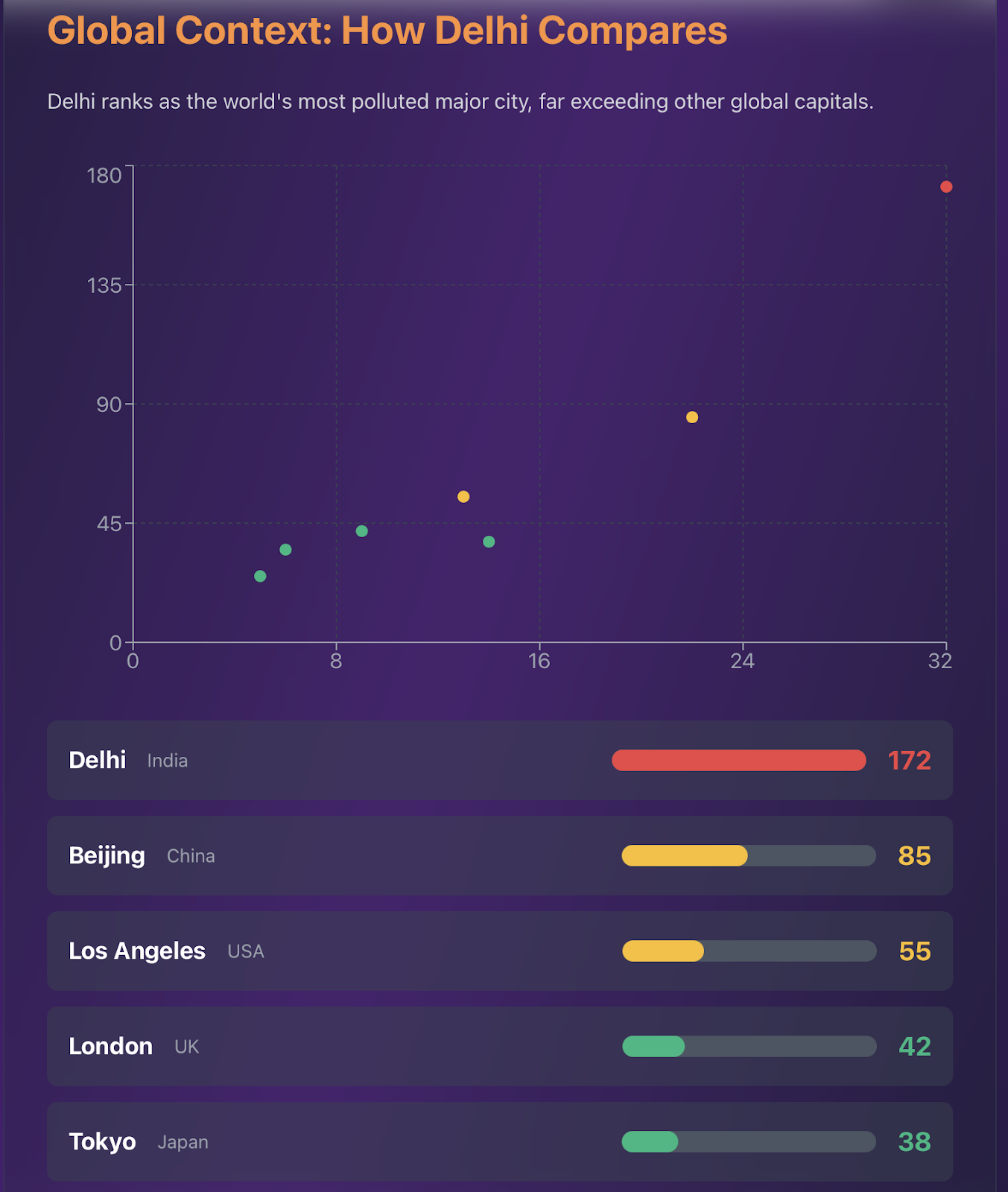

- Delhi’s ‘improved’ air quality figure of 172 is still more than three times worse than that of Beijing, a city that was once associated with air pollution but now has also introduced severe control measures.”

- Cities like London, Los Angeles, and Tokyo have dealt with air pollution successfully by making drastic policy changes, imposing strict emission standards, building comprehensive public transportation systems, and being politically determined over the long term.

Executive Summary

| This brief synthesises five years of air quality data (2020–2025) to demonstrate that Delhi’s pollution crisis is chronic, systemic, and year-round, not a seasonal anomaly. Delhi is used as a representative case of urban air failure in large, fast-growing cities, with global comparisons highlighting what sustained policy commitment can achieve. Five years of data show that Delhi’s air pollution is predictable, persistent, and policy-solvable. Incremental improvements prove progress is possible, but without long-term political commitment, Delhi will remain among the world’s most polluted cities—regardless of seasonal headlines. The evidence is settled. What remains unresolved is political will. |

The months of November and December are always accompanied by a familiar cycle of media coverage that portrays Delhi’s environmental crisis as suddenly top-of-mind, and current events across different media platforms echo similar sentiments. Politicians continue the blame game with each party accusing the other of failing the public with its air quality. The graphical presentation of severe deterioration in air quality is accompanied by an implication of impending danger or catastrophe.

However, perhaps we should not limit our observations strictly to winter’s environmental concerns. A review of air quality data over the last five years (2020-2025) provides an interesting contrast to what has historically been viewed as “seasonal pollution issues.” The air quality index (AQI) yearly average score between 2020 to 2025 has consistently demonstrated that air quality in India was not to be interpreted as a temporary “pollution emergency,” but instead a long-term, systemic failure with a sustained, low-grade pollution problem.

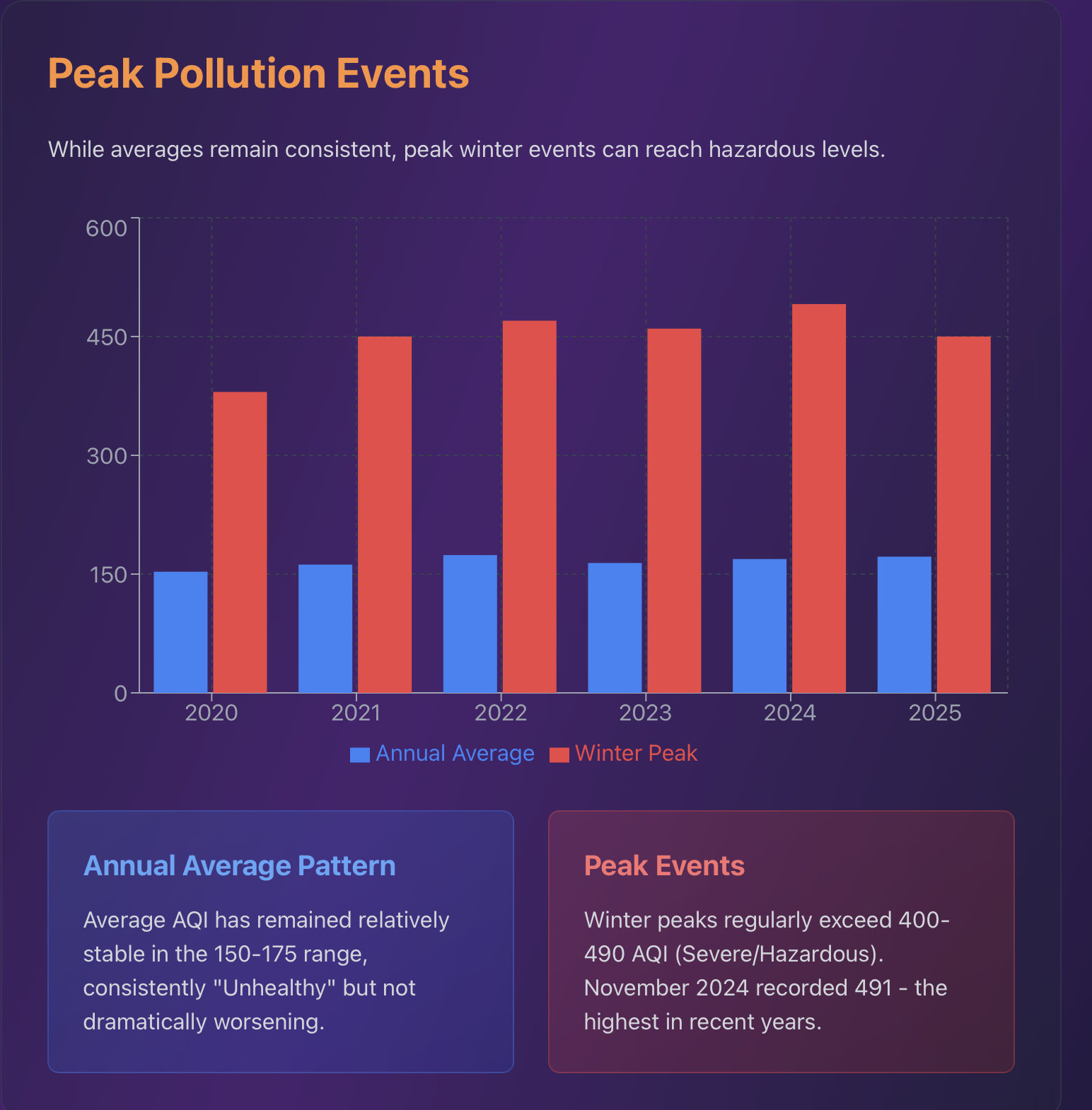

For example, the AQI scores represent a five-year ongoing crisis in terms of a longer-term impairment/decline of air quality. Average AQI scores for the last five years have been relatively high and have remained within a range classified as “Unhealthy”. AQI scores were 153 in 2020, 162 in 2021, 174 in 2022, 164 in 2023, and 169 in 2024; and the projected score will again fall within the same level of unhealthiness as the scores from the previous five years in 2025. Therefore, the data does not demonstrate a crisis occurring abruptly, but rather an extended, incremental issue that has finally culminated in the systemic collapse of air quality within and around the entire Delhi region.

The Chronic Reality: Understanding the Data

The examination of air quality trends in Delhi from 2020 to 2025 reveals a distinct pattern. Except for the year 2020, which was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic and was therefore an anomaly—when pollution levels were drastically lowered due to the lockdowns—the city has been living with an annual average Air Quality Index (AQI) of 162 to 174, which is unhealthy for all humans and not only for the sensitive ones. Thus, Delhi remains in the “Unhealthy” category every year. In 2024, Delhi managed to have 209 days with AQI less than 200, which is the greatest number of days with “Good to Moderate” air quality since the COVID lockdown year, and it signifies the actual victory over pollution control measures. Nevertheless, the yearly average remains at around 169-172, indicating that the improvements are there, but the core issue is still there.

The first eight months of 2025 saw the best AQI statistics for the last eight years, with an average of 172, while in 2024 it was 187. Also, PM2.5 levels decreased to 74 µg/m³, which is the lowest level since 2020. These are positive trends that deserve to be noted—they imply that some of the pollution control measures are working. But at the same time, they are also showing that the seasonal smog spikes are still dominating public knowledge, while the wasteful pollution all year round is less well-known.

The Winter Spike: A Predictable Pattern

The data highlights dramatic seasonal changes. The monsoon period of July to September brings down AQI to 85-100, a “Moderate” classification, but nevertheless much healthier air. However, AQI levels go up throughout the next five months. November usually has AQI over 350, with the 18th of November 2024 marking the poorest air quality in Delhi this season so far at 491 AQI, which has been labelled “severe plus”.

These fluctuations have been going on for years. The situation is pretty much the same every year due to a number of factors such as stubble burning in the northern Indian states, fireworks during Diwali, cold that leads to temperature inversions which keep the pollutants from rising, and still winds that do not allow the pollutants to disperse. The winter pollution crisis in Delhi is serious and nationwide, but still a part of the city’s environmental reality rather than an extraordinary occurrence.

Rethinking the Crop Burning Narrative

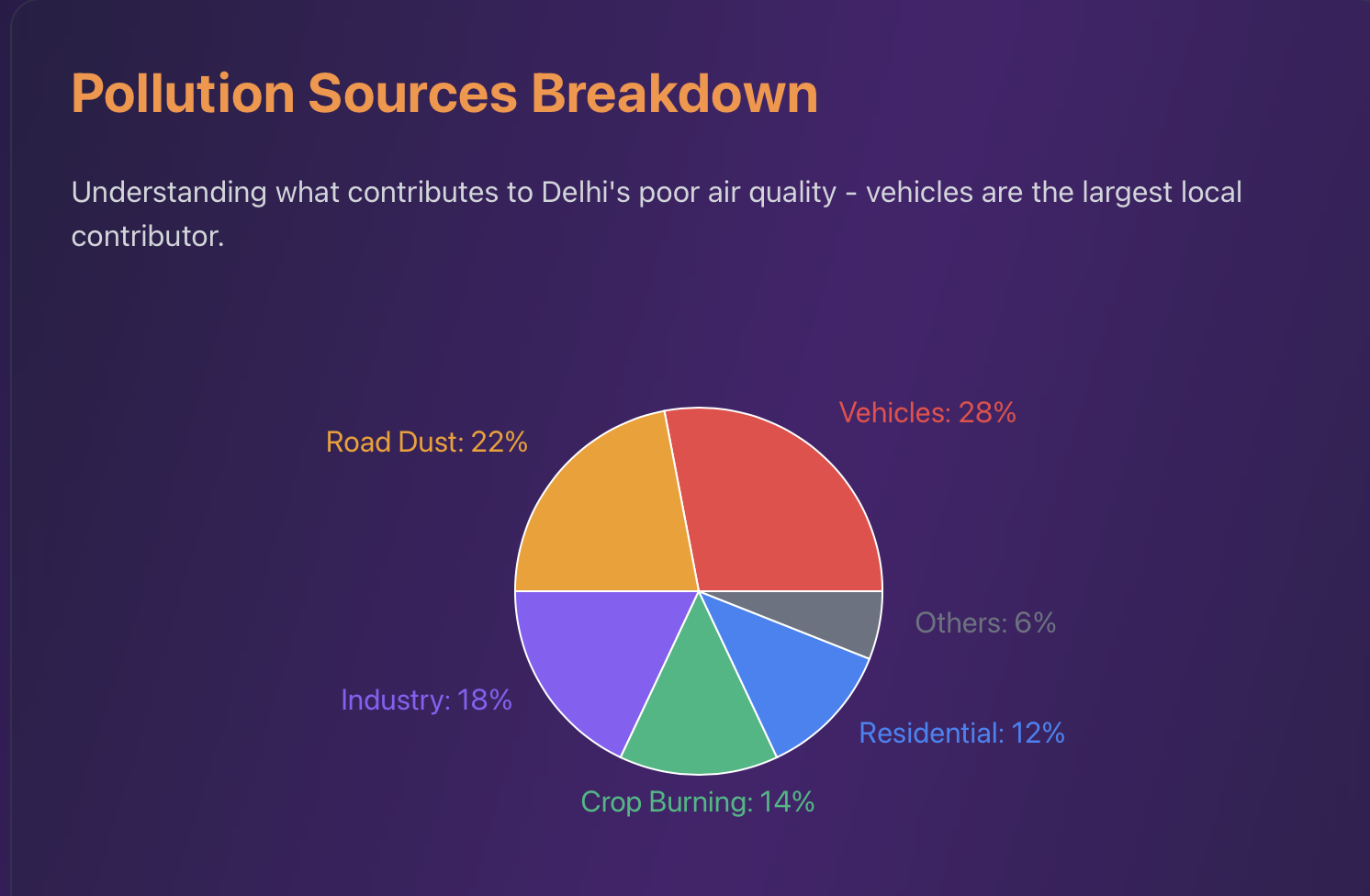

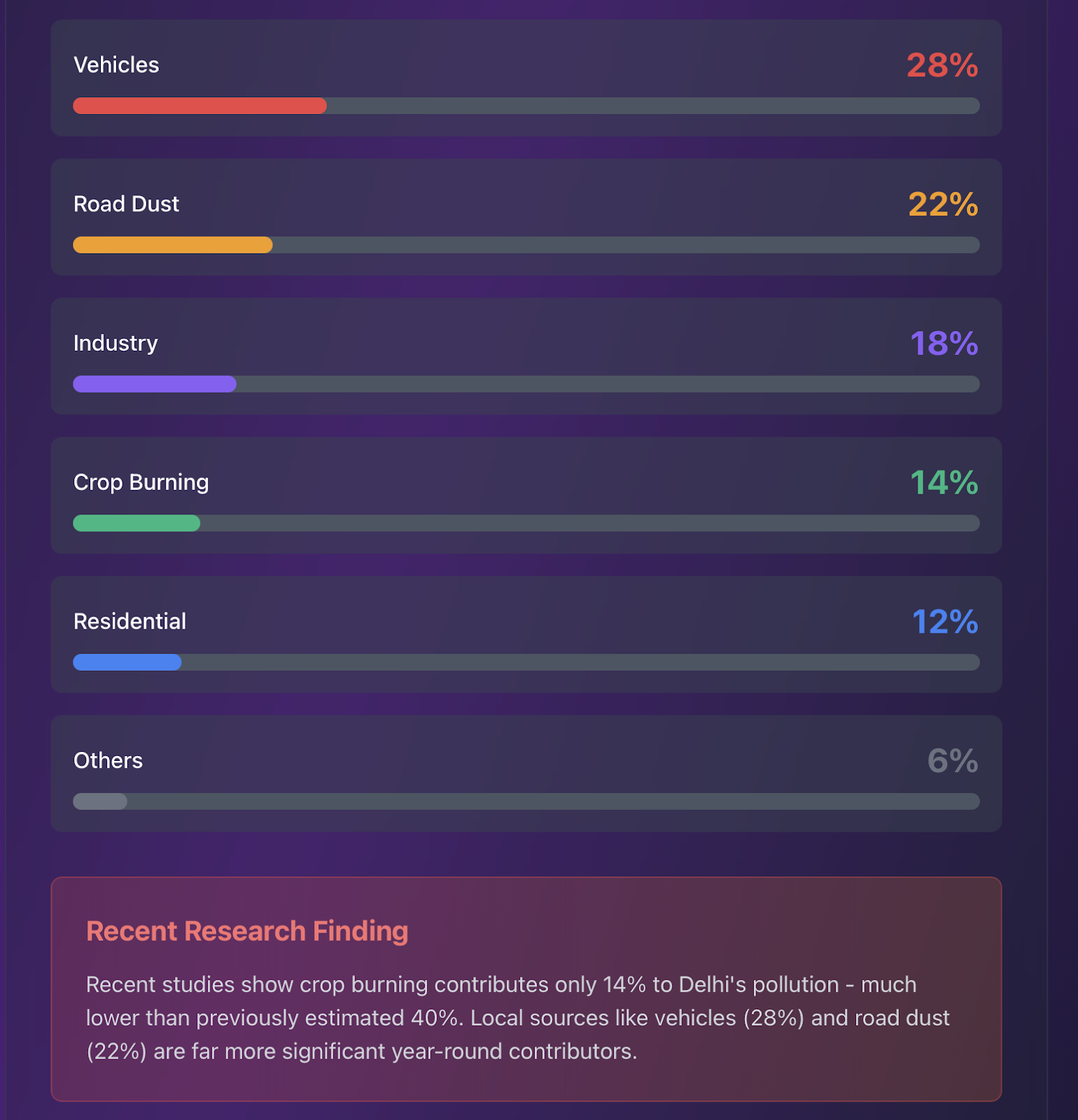

For a long time, the main story has attributed the pollution in Delhi to the burning of crop residues in Punjab and Haryana. It has been easier for politicians to blame others rather than to try to settle the matter at the local level. But new studies are now questioning this easy scapegoat.

A study of the data from 30 sensors installed in Delhi, Punjab and Haryana showed that the burning of straw was responsible for only 14% of Delhi’s pollutants, which is a considerably lower figure than previous assessments of up to 40%. During the period of 2015-2016 and 2022-2023, the number of farm fire incidents fell by 49% in Punjab and by 72% in Haryana, but the air quality in Delhi still got very poor in winter. Such a situation indicates that the problem is located elsewhere.

The Local Contributors: Where the Real Problem Lies

Motor vehicle emissions, road dust, industrial activities, construction dust, and burning of garbage are the major factors that worsen the air quality in Delhi. Current research indicates a more complicated scenario of pollution sources:

- Vehicles: The Major Offender: Vehicle emissions account for about 28% of fine particulate matter concentration, thus making the transportation sector the primary point of pollution in Delhi. Even with a network of more than 350 km of metro lines and 7,000 CNG buses, and despite the prohibition of older diesel and petrol vehicles, the surge in vehicle population has nullified these actions. The prevalence of two-wheelers, which pollute more per unit of fuel, exacerbates the situation.

- Road Dust: The Neglected Cause: Road dust is a major contributor and is responsible for around 22% of PM2.5 pollution. The combination of unpaved roads, construction activities, and heavy traffic creates a constant source of particulate matter that is often overlooked in policy discussions.

- Factories and Housing: Factories are responsible for around 18% of emissions. While most households (90%) use LPG for cooking, the 10% that use other means contribute more to winter PM2.5 levels due to the increased need for heating during that time (12%).

- Building and Rubbish: The rapid development of Delhi’s construction sector creates a lot of dust, and the burning of municipal solid waste and landfill fires worsens the situation. These are constant sources of pollution that are not as widely discussed as the seasonal crop burning problem.

The Global Context: How Bad Is It Really?

To grasp the pollution situation in Delhi properly, it is necessary to examine global comparisons first. New Delhi was the world’s most polluted major city in 2024. Additionally, India had 6 out of the 9 cities with the worst pollution worldwide. The city’s average AQI of 172 was a huge contrast to that of other top-polluted cities worldwide:

- Beijing: 85 (improved dramatically from previous years)

- Los Angeles: 55 (America’s most polluted major city)

- London: 42

- Tokyo: 38

- Sydney: 25

The comparison is very striking. Delhi’s “improved” air quality figure of 172 is still more than three times worse than that of Beijing, a city that was once associated with air pollution but now has also introduced severe control measures. Los Angeles, having a reputation for smog, however, has an AQI less than one-third of Delhi’s.

Cities like London, Los Angeles, and Tokyo have dealt with air pollution successfully by making drastic policy changes, imposing strict emission standards, building comprehensive public transportation systems, and being politically determined over the long term. The capital of China reduced its PM2.5 levels by more than 50% from 2013 to 2020 through coal cutbacks, vehicle restrictions, and industrial shift. These cases have shown us the ineffectiveness of controlling urban air pollution even in large cities.

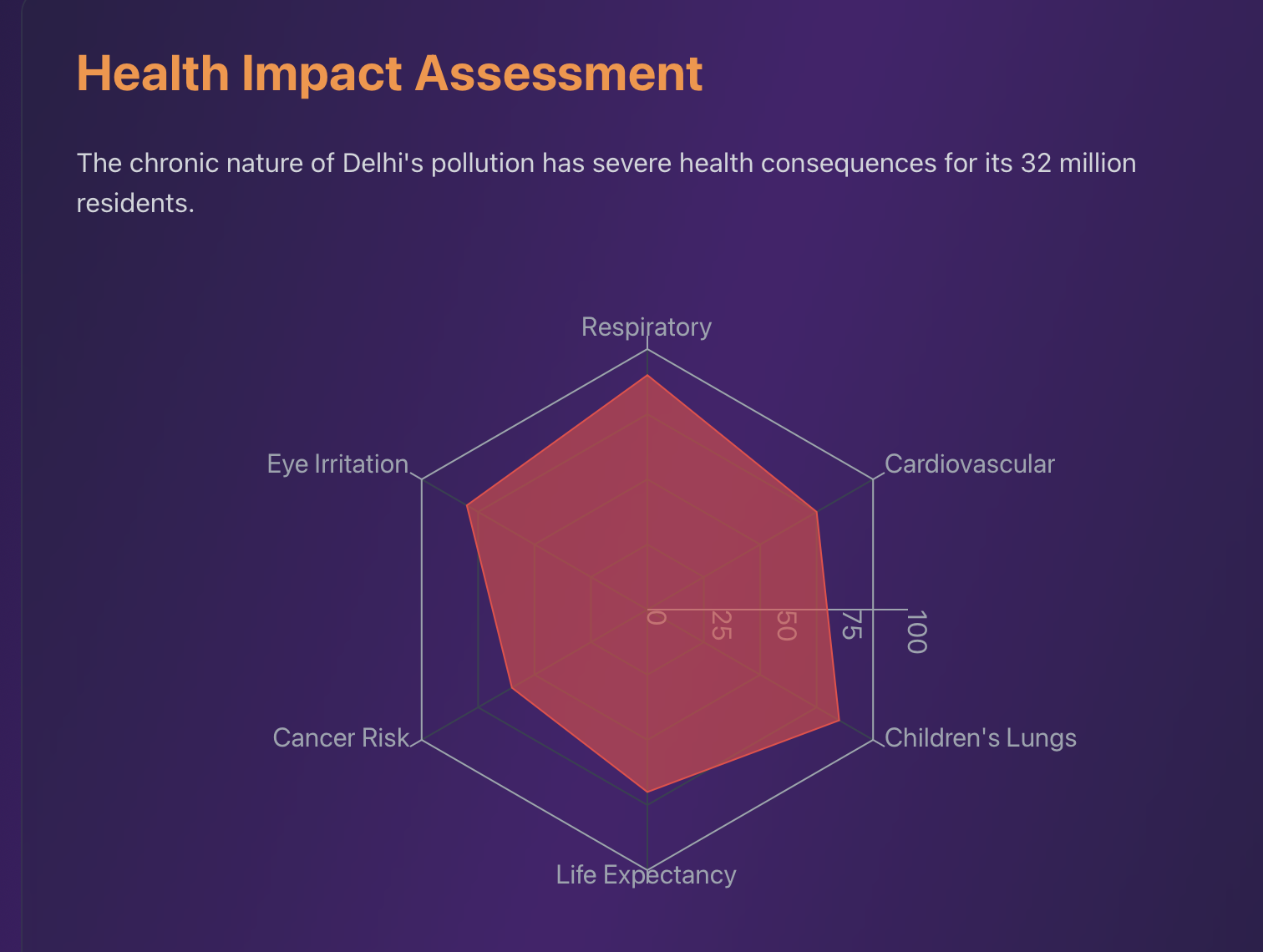

The Health Cost: A Silent Emergency

The discussion on pollution sources might still be ongoing, but the health impacts are already there and have been terrible. It is estimated that people living in Delhi, who are exposed to air pollution, lose nearly 10 years of life expectancy compared to World Health Organisation (WHO) standards. Roughly 90% of the children in Delhi are affected by the non-fulfilment of their lung capacity growth. In the year 2019, air pollution was held responsible for a total of 1.67 million deaths in India, direct to lung cancer, pneumonia, heart problems, and stroke.

These numbers correspond to actual people—families losing their loved ones earlier than expected, children getting respiratory problems, and old people who find it difficult to breathe even when they are not very active. The persistent pollution situation makes it a health-related issue throughout the year, instead of just the winter months being a temporary inconvenience.

Beyond the Blame Game: What Needs to Change

The data make clear that Delhi’s air pollution problem cannot be solved with the current reactive, seasonal approach. The annual pattern of panic, blame, and temporary measures has produced marginal improvements at best. What’s needed is a fundamental rethinking of the city’s approach to air quality.

- Year-Round Focus: Pollution control measures must operate throughout the year, not just during winter months. The fact that even “good” months see AQI levels in the 85-100 range (still “Moderate” and above WHO recommendations) demonstrates the need for sustained action.

- Addressing Local Sources: With vehicles contributing 28% and road dust 22% of pollution, local action must take priority. This means aggressive expansion of public transportation, strict enforcement of emission standards, promotion of electric vehicles, better road maintenance to reduce dust, and restrictions on private vehicle use during high pollution periods.

- Regional Cooperation: While crop burning isn’t the dominant factor previously believed, it still contributes 14% during critical periods. Effective solutions require genuine cooperation between Delhi, Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh, with the central government facilitating rather than simply mandating.

- Construction and Waste Management: Strict regulations on construction dust, proper management of municipal solid waste, and elimination of open burning must be enforced year-round.

- Public Awareness and Behaviour Change: Citizens must understand that their daily choices—vehicle use, waste disposal, fuel consumption—contribute to the problem. Public education campaigns should emphasise individual responsibility alongside government action.

Conclusion: Time for Honest Reckoning

The timeline of 2020-2025 reveals that the air pollution in Delhi is not a sudden occurrence but rather a continuous ailment that is the result of a long-standing urban expansion, poor infrastructure, lack of proper regulations for the environment, and political indecision. It is the winter periods that draw the most attention, but they are merely signs of a problem that persists throughout the year.

It would be incorrect and perilous to dismiss the current issues as mere propaganda. There is a clear, extensive, and very serious impact on health. Nevertheless, the seasonal contention and the pointing of fingers have become a form of ritual that replaces significant action. The actual propaganda might well be the story that Delhi’s pollution problem can be solved through odd-even schemes, emergency shutdowns, and the accusation of neighbouring states.

Feasible progress—the improvements noted in the years 2024-2025 are proof that continuous efforts can produce results. However, these modest gains, although they are a reason for celebration, are still not enough. Delhi has to undergo the same commitment that transformed the air in London, Los Angeles, Tokyo, and Beijing. It calls for political bravery to put long-term public health over short-term economic interests, to pour enormous amounts into public infrastructure, and to make both the government and the public accountable.

The data has been very clear for five years. What remains is to see whether we will start listening and acting properly or just keep repeating the annual cycle of panic and neglect. The answer for the 32 million individuals who inhale Delhi’s air every day might be literally a matter of life and death.

| Data Sources: Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), Commission for Air Quality Management (CAQM), AQI.in, IQAir World Air Quality Report, Government of India Press Information Bureau, Ministry of Earth Sciences, The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) |

Divyanka Tandon holds an M.Tech in Data Analytics from BITS Pilani. With a strong foundation in technology and data interpretation, her work focuses on geopolitical risk analysis and writing articles that make sense of global and national data, trends, and their underlying causes. Views expressed are the author’s own.