- On the 1st of January 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a memorandum of understanding at a high-profile event in Addis Ababa hosted by Abiy Ahmed.

- Denouncing the deal, which it saw as a fundamental infringement of its territorial integrity and sovereignty, the Somali government immediately expelled the Ethiopian ambassador and complained to the UN Security Council.

- Following talks in Ankara mediated by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the two sides issued a joint declaration on 11 December 2024, announcing that they agreed to launch technical talks by February 2025 and reach a final agreement within four months.

- In addition to offering the possibility of better economic and political relations, it could also lay the foundations for greater security cooperation to tackle extremism and deal with other regional conflicts and crises.

After many decades of tensions, including a bitter and brutal war in the 1970s, relations between the two countries have recently been strained by Ethiopia’s efforts to secure access to the sea through Somaliland, which broke away from Somalia in the 1990s. Following Turkish mediation, the two countries are set to start negotiations. So, what exactly have they agreed on, and what could it mean for Ethiopia, Somalia, the wider region, and Somaliland?

Around the world, neighbouring countries have confrontational or even conflictual relations. This can be centred on any number of issues. Sometimes it can be based on profound ethnic or religious differences or because one country supports separatist efforts in the other. At other times, more historical grievances, such as reclaiming lost territory, can be a factor. Alternatively, tensions can also be based on competition for resources or broader strategic issues like control of territory or access to the sea. On occasion, all these factors can come into play.

A good example is the relationship between Ethiopia and Somalia. For over 60 years, the two countries have had problematic relations, at times even resorting to war and invasion. But could things be about to improve?

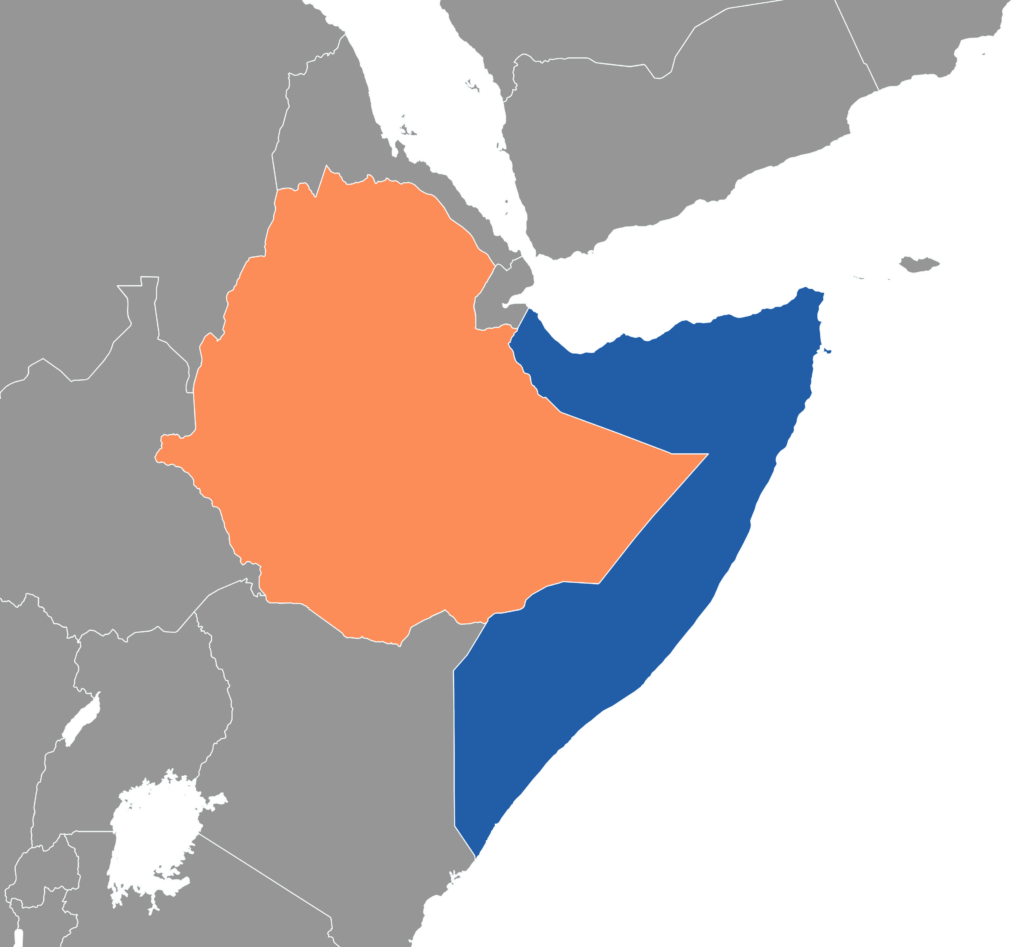

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the Republic of Somalia lie in East Africa. Landlocked, Ethiopia has a highly mixed population comprising over 80 distinct ethnic groups. These include Oromos, Amhara, Tigrayans, and a large Somali community in its east. By contrast, Somalia is one of the least ethnically diverse countries on the continent. Almost all its inhabitants are ethnic Somalis. However, the society is divided by a highly complex network of clan affiliations. It’s also divided, as the northern region of Somaliland broke away at the start of the 1990s. While Ethiopia and Somalia have long histories stretching back to antiquity, the story starts in the late 19th century when European powers began colonizing Africa.

While Ethiopia, then known as Abyssinia, was never formally conquered, the Somali-inhabited lands on the coast were divided between the French, the British, and the Italians. Meanwhile, in 1887, the Ethiopian Empire seized control of the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region—a move Britain accepted a decade later.

In 1960, as decolonization gathered pace, British and Italian Somaliland united to form a new independent state: the Somali Republic. However, relations between the new country and neighbouring Ethiopia were strained from the start as Somali nationalists sought to unite all Somali-inhabited areas into a single Greater Somalia.

In addition to the French-held territory, which later became the Republic of Djibouti, and parts of Kenya, the claims also included the Ogaden region.

From there, tensions between the countries dramatically escalated in 1969 when a Marxist army officer, General Muhammad Siad Barre, seized power in Somalia. Promising to unite all the Somali territories, he began providing political and military support to Somali insurgents in the Ogaden. However, it wasn’t until the overthrow of Ethiopia’s pro-Western Emperor Haile Selassie that Somalia saw its chance to act.

In July 1977, Somalia, supported by Somali insurgents, invaded. But while they initially made substantial gains, the situation soon changed. The Soviet Union turned against Siad Barre and instead supported the new communist military regime in Ethiopia. As a result, by March 1978, Ethiopian forces had retaken the Ogaden. Defeated, Somali troops were forced into a humiliating withdrawal. The Ogaden War marked a significant shift in relations between Ethiopia and Somalia. Although tensions persisted throughout the 1980s, direct conflict transitioned to indirect confrontation as both countries supported rebel groups on each other’s territory. The war also had broader implications. While Soviet-backed Ethiopia emerged as a regional power, the defeat undermined Siad Barre, who now shifted his allegiance to the West. However, the end of the Cold War changed everything for both countries, paving the way for the problems we see today.

In Ethiopia, the loss of Soviet support led to the overthrow of the military regime by a coalition of ethnic rebel groups. As part of this, Ethiopia accepted Eritrea’s independence. This would have profound effects, as it now meant that Ethiopia lost direct access to the Red Sea and became a landlocked country. In January 1991, Siad Barre was finally overthrown. However, rather than usher in a new period of stability for Somalia, the country descended into anarchy and chaos as central government authority collapsed.

Meanwhile, as the rest of the country fell into civil war, the northern area that had once been British Somaliland seized the opportunity to break away, declaring independence as the Republic of Somaliland on the 18th of May 1991.

Over the following decades, a complex situation emerged in the region. As Somalia collapsed, Somaliland became an island of stability. However, despite this, the international community ignored its regular calls for recognition. Although many countries, including Britain and the United States, were sympathetic to its case for independence and would even meet with its officials, the general view was that African states should take the lead and recognize it first. Amidst all the churns, Ethiopia closely monitored developments in Somalia, fearing that they could feed broader regional instability.

This came to a head in 2006 when Ethiopia launched a full-scale military invasion to drive out an Islamist group that had gained control of the Somali capital, Mogadishu. Following this, Ethiopia also supported Somalia’s gradual efforts to rebuild under a federal government, playing a central role in an African Union peacekeeping mission to the country and assisting with Somali efforts to defeat Al-Shabaab, another Islamist insurgency that had gained ground in Somalia.

By 2018, relations between Ethiopia and Somalia were strengthening, particularly following the emergence of a young reformist prime minister in Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed Ali, who promised greater regional and international cooperation. However, as Ethiopia steadily enhanced its status, becoming an increasingly assertive economic and political actor, the issue of sea access, lost with Eritrea’s independence, came to the forefront once more. And it’s this that sparked renewed tensions with Somalia.

On the 1st of January 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a memorandum of understanding at a high-profile event in Addis Ababa hosted by Abiy Ahmed. In return for a long-term lease over a port facility on the Red Sea, which could be used for both commercial and military purposes, Ethiopia would recognize Somaliland. Needless to say, the announcement was greeted with jubilation in Somaliland.

But while many Somalilanders saw it as the crucial breakthrough they needed to set off a train for further recognition and even pave the way for full international acceptance and perhaps UN membership, the announcement caused an immediate outcry in Mogadishu.

Denouncing the deal, which it saw as a fundamental infringement of its territorial integrity and sovereignty, the Somali government immediately expelled the Ethiopian ambassador and complained to the UN Security Council. From there, tensions continued to escalate.

Stepping up efforts to win African and international support for its position, Somalia highlighted how the Ethiopian decision would undermine its stability while it was trying to re-establish its internal authority and rebuild its regional standing.

Having even suggested military action, Mogadishu also started to build closer defence and security relationships, including with Egypt, which has a long-standing dispute with Ethiopia. Ethiopia was seemingly undeterred. Addis Ababa stood by its decision, reaffirming its commitment to the port deal just a few months later.

But as relations steadily deteriorated and it even appeared that the two countries were heading for confrontation, things suddenly changed. Turkey, which maintains close ties to both sides, stepped in to de-escalate the situation. Following talks in Ankara mediated by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the two sides issued a joint declaration on 11 December 2024, announcing that they agreed to launch technical talks by February 2025 and reach a final agreement within four months. Acknowledging the potential benefits to Ethiopia from assured access to the sea, they agreed to work towards a settlement that would allow Ethiopia to enjoy reliable, secure, and sustained access to the sea under Somalia’s sovereign authority. While it remains to be seen whether a final agreement can be reached, a settlement would undoubtedly have profound implications.

The Horn of Africa has long been a hotspot for conflict and instability. In addition to offering the possibility of better economic and political relations, it could also lay the foundations for greater security cooperation to tackle extremism and deal with other regional conflicts and crises. In this sense, the declaration has been widely welcomed internationally, with statements of support from the UN Secretary-General, the US State Department, and the British Foreign Office, amongst others. More broadly, the deal is a significant win for Turkey.

Hailed by Erdoğan as a historic step towards peace and cooperation in the Horn of Africa, Ankara’s mediation effort highlights its growing influence as a political and diplomatic actor in Africa. This will almost certainly increase its standing as a regional power broker.

Meanwhile, the obvious loser in all this is Somaliland.

Having pinned its hopes on Ethiopian recognition, which many thought would finally lead to broader African and international acceptance, its optimism seemed premature.

References:

- Kaledzi, Isaac, and Solomon Muchie. “Somaliland Unfazed by Somalia-Ethiopia Compromise – DW – 12/16/2024.” dw.com, December 16, 2024. https://www.dw.com/en/somaliland-unfazed-by-somalia-ethiopia-compromise/a-71065172.

- Kalkidan Yibeltal in Addis Ababa & Basillioh Rukanga in Nairobi. “Ethiopia and Somalia Reach Deal in Turkey to End Somaliland Port Feud.” BBC News, December 12, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cvgr7v1evvgo.

- Lawal, Shola. “Somaliland Goes to the Polls amid Ethiopia-Somalia Port Deal Row.” Al Jazeera, November 14, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/11/13/somaliland-goes-to-the-polls-amid-ethiopia-somalia-port-deal-row.

- Tyson, Kathryn. “Africa File Special Edition: Ankara Declaration Reduces Ethiopia-Somalia Tensions but Leaves Unresolved Gaps.” Institute for the Study of War, December 18, 2024. https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/africa-file-special-edition-ankara-declaration-reduces-ethiopia-somalia-tensions-leaves.

Prajwal K M holds a Master’s in Diplomacy, Law, and Business with a specialization in Economics and Foreign Policy. He is currently a consultant at the Nation First Policy Research Centre (NFPRC), a Delhi-based think tank working on policy design and implementation with the government. Formerly Deputy Editor at SamvadaWorld, his work focuses on the political and economic landscapes of West Asia and North Africa.