- Prithvi Narayan Shah saw Nepal as ‘a yam between two boulders’, India (then under the British East India Company rule) and China (under the Qing dynasty).

- The 1950 India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship forms the bedrock of the special relations that exist between India and Nepal.

- In 2008, following a decade-long civil war and a popular uprising, Nepal’s monarchy was abolished, and the country was declared a federal democratic republic.

- The recent protests are a matter of critical strategic concern for India, as Instability in Nepal poses several direct and indirect threats to India’s interests, with security being foremost among them.

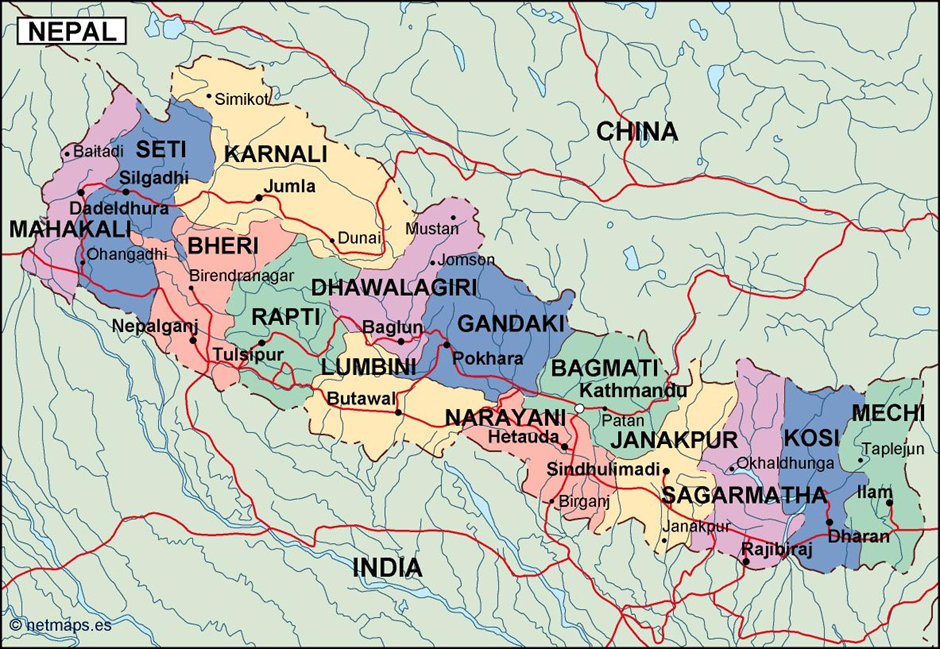

As close neighbours, India and Nepal share unique ties of friendship and cooperation characterised by an open border and deep-rooted people-to-people contacts of kinship and culture. There has been a long tradition of free movement of people across the border. Nepal shares a border with five Indian states – Sikkim, West Bengal, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand. The India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1950 forms the bedrock of the special relations that exist between India and Nepal.

Nepali citizens avail themselves of facilities and opportunities on par with Indian citizens in accordance with the provisions of the treaty. Nearly 8 million Nepali citizens live and work in India. Indians also live in Nepal. According to India’s Ministry of External Affairs, approximately 6,00,000 Indians are living/domiciled in Nepal. These include businessmen and traders who have been living in Nepal for a long time, professionals (doctors, engineers, IT professionals, IT personnel ), and labourers ( including seasonal/migratory in the construction sector ).

A large number of Nepali Gorkhas also serve the Indian army and, after retirement, return to Nepal and survive on Indian pensions. Over 1,25,000 such pensioners are living in Nepal. However, in spite of the strong people-to-people ties India-Nepal relations have had their ups and downs both during the rule of the Nepali monarchy and the post-monarchy phase.

The Origins Of The Nepali Monarchy: A Brief Historical Overview

The modern political unification of Nepal is credited to King Prithvi Narayan Shah (1723-1775 ), who established the Shah Dynasty and laid the foundations of a centralised Nepalese state. Prithvi Narayan Shah recognised the vulnerability of small hill kingdoms in the face of growing European colonialism and regional fragmentation. His successful campaigns against Kathmandu valley kingdoms like the Malla and the annexation of the strategic hill regions created a united Nepal by the late 18th century. Over time, this monarchy came to represent not just political power but also the preservation of Nepal’s distinct identity in a volatile region.

Crucially, it was Prithvi Narayan Shah who saw Nepal as “a yam between two boulders”, India (then under the British East India Company rule) and China (under the Qing dynasty). His strategic insight became the cornerstone of Nepal’s foreign policy. The monarchy would thereafter pursue a policy of cautious diplomacy, balancing relations with both countries while fiercely protecting its sovereignty.

However, the monarchy’s relationship with India has been fraught with ambiguities, paradoxes, and shifting alliances. Despite deep cultural, religious, and ethnic ties, the monarchy in Nepal has not always acted as a friend or ally to India.

However, by the mid-19th century, real power in Nepal shifted away from the monarchy. Following the Kot massacre of 1846, Jung Bahadur Rana established the hereditary Rana Prime Ministership, relegating the Shah kings to ceremonial roles. The Ranas ruled Nepal as autocrats, aligning closely with the British colonial government in India.

India’s Relations With The Nepali Monarchy

The foundation of modern India-Nepal relations was laid in the 1950 India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship. This treaty established a framework for the special relationship between India and Nepal, focusing on mutual security, territorial integrity, and reciprocal treatment of citizens. In the 1950s, the rulers of the Rana Kingdom of Nepal welcomed close relations with newly independent India, fearing the overthrow of their autocratic rule by Chinese-backed communists after the success of the Chinese Communist revolution and the establishment of the Chinese Communist Government on October 1st, 1949. However, Rana’s power in Nepal collapsed within three months of the signing of the 1950 India-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship.

The birth of the Indian Republic in 1950 coincided with Nepal’s internal turbulence, and India played a quiet but critical role in restoring the Nepali monarchy to real political power. King Tribhuvan, a figurehead under the Rana regime, sought asylum in the Indian Embassy in Kathmandu in 1950. India facilitated his safe passage to New Delhi, effectively signalling its disapproval of the Rana’s autocracy.

In exile, King Tribhuvan garnered Indian support, culminating in the 1951 Delhi Accord. This agreement led to the downfall of the Rana regime and the restoration of power to the monarchy under a constitutional framework. India saw this as a strategic win, replacing an oligarchic and isolationist Rana regime with a friendly monarchy that owed its re-empowerment to New Delhi. The monarchy was viewed as a natural cultural and civilizational ally, a Hindu Kingdom with historical ties to Indian traditions, religion, and values.

However, King Mahendra, who succeeded Tribhuvan in 1955, began consolidating power and adopting a policy of equidistance, often interpreted in India as a tilt toward China. The Indian Military Mission, set up in the 1950s to train Nepal’s armed forces, symbolised India’s security partnership with Nepal. Its expulsion in 1969, at the behest of King Mahendra, was a diplomatic snub that underscored the monarchy’s growing tilt towards China. Nepal began to strengthen economic and infrastructural ties with China, most notably through the construction of the Kathmandu-Kodari highway, which linked Nepal to Tibet. This road, completed in the 1960s with Chinese aid, continues to be perceived by India as a strategic threat, given its proximity to the Indian border.

The Nepali monarchy’s relevance began to wane in the late 20th century as democratic movements gained momentum. The 1990 People’s Movement forced King Birendra to accept a constitutional monarchy, and the subsequent rise of the Maoist insurgency further destabilised the institution. In 2008, following a decade-long civil war and a popular uprising, Nepal’s monarchy was abolished, and the country was declared a federal democratic republic. As the Maoist insurgency surged, Nepal’s king Gyanendra sought military help from India and China. India was committed to supporting Nepal’s peace process and pushed for the return of democracy. Gyanendra tried to circumvent this pressure by cosying up once more to China. Thus, even at its lowest ebb, the Nepali monarchy viewed India more as a troublesome neighbour than as a cultural kin or ally.

India’s Relations With The Republic Of Nepal Post 2008

By the late 2000s, India had recalibrated its policy towards Nepal. The abolition of the monarchy in 2008, following a decade-long civil war and the success of the Maoist rebels, was met with little resistance from New Delhi. Despite India’s historical preference for monarchies, it acknowledged the impracticability of supporting a royal institution that opposed its geopolitical goals, choosing instead to collaborate with democratic forces in Nepal, including the Maoists, understanding that the power structure in Nepal had fundamentally changed.

However, the anti-India nationalist sentiment in Nepal continues to grow due to the historical fact of India having been associated with most of the political changes in Nepal. Whether it was the anti-Rana agitation when India supported King Tribhuvan or the support to democratic forces in the years leading up to the Jan Andolan of 1989-1990 that led to the dismantling of the Panchayat regime, India has sided with popular aspirations for greater democracy in Nepal.

However, despite this, post-2008 India’s relations with Nepal’s Maoist governments have been tense and hostile, with Nepal’s governments alleging Indian interference in Nepal’s internal affairs. This sentiment gained ground in 2008 when India played a role in facilitating a settlement between the Madhesi parties that were agitating for a more inclusive and equitable society and the Nepali government 2008. At the time, Nepal’s capital Kathmandu was rife with rumours that India had instigated the Madhesi agitation, and that India was supporting the armed Madhesi groups in Nepal’s Terai region. The Madhesis are people of Indian origin in Nepal who believe that they are being discriminated against by the Nepali government.

Also straining India’s relations with the Republic of Nepal is the Limpiyadhura – Lipulekh controversy, which is one of the most enduring and emotive border disputes between India and Nepal. At the heart of the dispute lies about 370 square kilometres of rugged Himalayan terrain near the tri-junction with China. This area includes:

Lipulekh Pass, a high-altitude route historically used for trade and pilgrimage to Kailash Mansarovar. Kalapani Valley has been under Indian military control since the 1962 India-China war. Limpiyadhura Ridge, claimed by Nepal as the true origin of the Kali River, which defines the India-Nepal border under the 1816 Sugauli Treaty. However, some 19th-century British colonial era maps placed Limpiyadhura as the river’s source (favouring Nepal), while other colonial era maps aligned with India’s claims.

In Nepal, this issue has become a powerful symbol of nationalism and sovereignty. Since the 1990s, it has been a rallying cry for politicians across the spectrum – from the CPN-UML to the Maoists, often invoked during the elections. The controversy reached new heights in 2020, when Nepal amended its constitution and official map to incorporate these disputed areas, sparking intense diplomatic relations with India.

Nepal’s Maoist Movement And Its Geopolitical Alignment With China

The communist movement in Nepal emerged in the late 1940s, drawing inspiration from the rise of global communism, especially the Russian communist revolution of 1917 and the Chinese communist revolution of 1949. This movement was a reaction to Nepal’s entrenched feudal system, absolute monarchy, and pervasive social inequalities. The Communist Party of Nepal (CPN) was officially founded on September 15, 1949, in Kolkata, India.

The most significant chapter of Nepal’s communist history is the Maoist insurgency, which began in 1996. Led by the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), the insurgency aimed to overthrow the monarchy and establish a people’s republic through a violent revolution. During this period, the Maoists under the leadership of Pushpa Kamal Dahal mobilised large sections of the population, particularly from indigenous communities, Dalits, and women who felt excluded by the hill Brahmin and Chhetri communities. The Chhetris still dominate the Nepali army and other security forces, whereas the hill Brahmins dominate Nepali politics and administration. The Maoist insurgency was not only a political but also a social revolution, challenging the traditional hierarchies of Nepali society.

The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) of 2006 ended the civil war in Nepal, and the Maoists entered mainstream politics, participating in the 2008 Constituent Assembly elections. In 2008, Nepal became a republic by abolishing the monarchy. In the Constituent Assembly elections, the Maoists emerged as the largest party and formed the government.

Once in power, the Maoist leadership, particularly Dahal and his inner circle, were accused of abandoning the principles of Marxist-Leninism and Maoism in favour of personal and political gains instead of advancing the Maoist revolutionary goals of social equity and justice. This failure of the Maoists in the realm of governance and administration has led to accumulated loss of faith among Nepal’s youth in the current political process, which was one of the factors which resulted in the September 2025 protests by Nepal’s youth which forced the resignation of Nepal’s prime minister KP Sharma Oli following his government’s decision to impose a social media ban.

Nepal signed the memorandum of understanding (MOU) on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in May 2017, when its relations with India were at their lowest. In 2015, Nepal witnessed a violent protest at the Nepal-India border by the Madhesi community, which shares close socio-cultural and matrimonial ties with India, in response to the newly promulgated constitution. Madhesis complained that the provisions related to citizenship in the new constitution discriminated against them due to their origin and close socio-cultural ties with India. The protests disrupted the India-Nepal border trade, and Nepal accused India of supporting the Madhesis. Then, an alleged border blockade by India in 2015 significantly impacted India-Nepal ties. An aggrieved Nepal promptly identified the open border with India as a security threat in its first-ever National Security Policy of 2016.

This, along with Nepal’s signing of the Trade and Transit Agreement with China in 2016, was seen as a diplomatic setback for India after the BRI, as it would reduce Nepal’s reliance on India for third-country trade. However, there is a lack of progress regarding BRI’s key projects in Nepal, such as the Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network that aims to connect Kathmandu and Tibet through railways, roads, and digital infrastructure, due to Nepal’s concerns about the unclear financial terms of Chinese loans.

Implications Of The September 2025 Nepal Protests For India’s National Security

The recent political turmoil in Nepal, which resulted in the resignation of the Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and widespread protests led by the youth, may appear to be an internal affair. But for India, it’s a matter of critical strategic concern. Instability in Nepal poses several direct and indirect threats to India’s interests. Security is foremost among them. An open border with Nepal is both a boon and a bane.

Political chaos and a breakdown of law and order can lead to a surge in cross-border smuggling, human trafficking, and an increase in the activities of anti-India elements. The potential for a security vacuum in Nepal could be exploited by hostile actors, particularly Pakistan’s ISI, to foment trouble in India. China’s growing influence is also a concern. As India’s clout has been waning in a politically unstable Nepal, China’s footprint has been enlarging. China has been actively engaged in Nepal through its BRI and various infrastructure projects, including roads and railways. At the same time, the youth protestors are wary of any perceived interference by India in Nepal’s internal affairs.

In the context of the September 2025 youth protests in Nepal, India must resist the temptation to influence or intervene in Nepal’s internal politics, as past attempts to do so, such as the 2015 unofficial border blockade, have been counterproductive, fostering anti-India sentiment and pushing Nepal closer to China. Instead, India should focus on building up its soft power in Nepal by promoting educational and cultural exchanges, which will promote goodwill among the Nepali public and strengthen the bilateral relationship. India should also accelerate its developmental assistance to Nepal by completing existing projects on time and investing in new ones that benefit the Nepali public directly. Finally, India should open new channels of communication with the emerging political leaders and youth activists in Nepal. Understanding their aspirations and grievances is essential if India is to formulate its foreign policy towards Nepal successfully.

References:

- Asia Society (2023). Nepal’s Geopolitical Crossroads: Balancing China, India, and the United States. Retrieved from https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/nepals-geopolitical-crossroads-balancing-china-india-and-united-states

- Chauhan, S (2024). Changing Borders: India- Nepal Relations in a Changing Geopolitical Landscape. Pentagon Press Chauhan, S (2025). Nepal’s Monarchy and India: A Historical Relationship of Complexity and Contradictions. Retrieved from https://bharatshakti.in/nepals-monarchy-and-india-a-historical-relationship-of-complexity-and-contradictions/

- Mulmi, A. (2022). All Roads Lead North: Nepal’s Turn to China. Context Rae, R. (2021). Kathmandu Dilemma: Resetting India-Nepal Ties. Vintage Books Singh, M, & Yadav, A (2024 ). India and Nepal: Redefining a Relationship. Retrieved from https://www.ijfmr.com/papers/2024/6/32772.pdf#:~:text=An%20open%20border%20between%20India%20and%20Nepal

- Tharoor, S (2025). Nepal Gen Z Revolt: What Should India Do? retrieved from https://www.ndtv.com/opinion/why-the-nepal-gen-z-movement-poses-a-risk-for-india-too-9279058

Dhruv Ashok is a PhD research scholar from Christ (Deemed to be University), Bangalore. He writes on current affairs and international politics. His areas of interest include conflict resolution and historical narratives. Views expressed are the author’s own.