- Air defence determines political negotiating leverage, escalation control, and ultimately, the freedom to use force.

- Sovereignty is often limited to assembly or subsystem level development, while critical upstream and downstream layers remain under external control.

- Imported defence systems often function as ‘black boxes,’ making it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to modify seekers, algorithms, or counter drone swarms and saturation attacks.

- Air defence “independence” ultimately requires end-to-end control of the entire mission sequence from chips through sensors, through missiles, software, integration and certification.”

When Air Defence Turns into a Strategic Weakness

In modern combat, air defence has become the cornerstone of national survival, rather than an ancillary capability. In a battlefield environment marked by autonomous drone swarms, electronic warfare, hypersonic glide vehicles, long-range cruise missiles, and precision-guided weapons, air defence dictates that a nation can safely commit ground troops to combat. The inability to defend national skies places a nation at a great risk of strategic immobility well before the deployment of ground forces. Air defence, therefore, determines political negotiating leverage, escalation control, and ultimately, the freedom to use force.

One of the most intricate, high-cost air defence systems currently deployed exists in India. However, behind this impressive inventory lies a critical weakness-a strong reliance on foreign software, systems, subsystems, and industrial inputs. This dependence has often been justified as strategic pragmatism. In 2025, an in-depth study was conducted by the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) on Russian air defence manufacturing. The finding demonstrated that disruptions to industrial supply lines can cause even the most powerful air defence systems to lose their efficacy. This is not merely an external case study for India, but a direct warning that needs to be formally acknowledged.

The Russian Air Defence Paradox

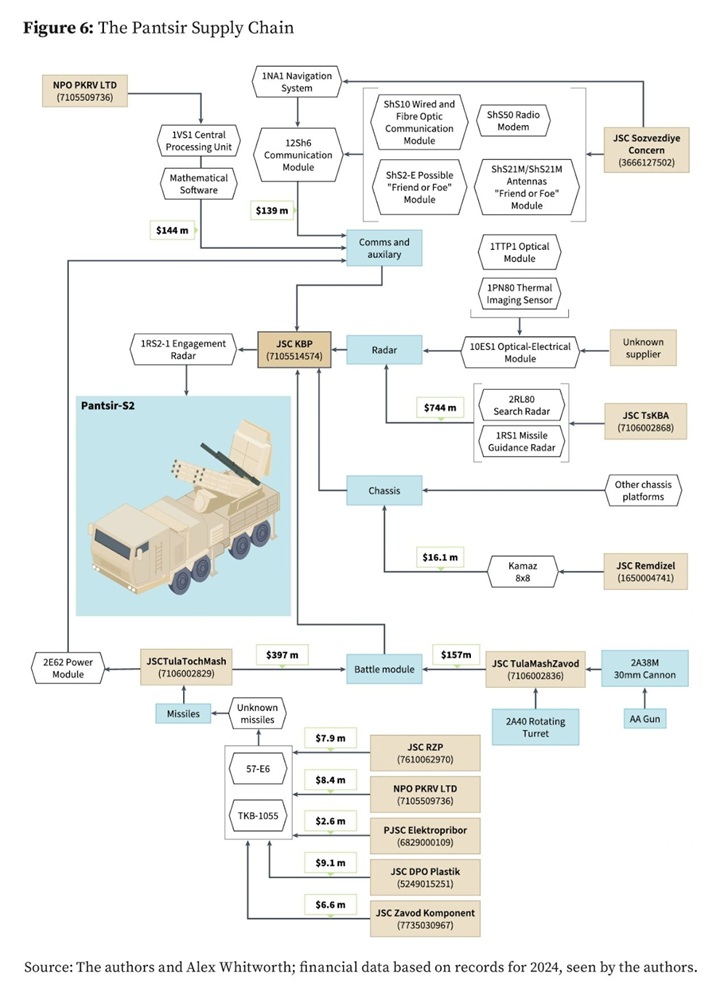

Many analysts consider Russia’s S-400 and Pantsir air defence systems to be among the most powerful in the world. The 2025 RUSI analysis, however, highlights a strategic paradox: these systems rely on a precarious, internationally dependent industrial foundation while projecting battlefield strength. The lack of industrial sovereignty, rather than pure technical proficiency, is the core issue.

Pantsir Air Defence System

| Component | Primary Producer | Key Suppliers |

| System integration & assembly | KBP (Tula) | Unknown/classified |

| 2RL80 search radar | TsKBA (Tula) | NPO PKRV, Rezonans, RUSNIT, Radis, NPP ISTOK |

| 1RS2-1 guidance radar | KBP (Tula) | Unknown (in-house) |

| TKB-1055 missile | KBP (Tula) | TulaTochMash; others partly unknown |

| 30 mm cannon | TulaMashZavod | Unknown secondary suppliers |

| Communications & IFF (12Sh6 series) | Sozvezdiye (Voronezh) | Unknown electronics suppliers |

| Navigation, CPU & power modules | Russian defence firms | Unknown/undisclosed |

The Elbrus-90 microprocessor, which was traditionally manufactured outside of Russia, is a central computing component of the S-400. The capability of Russia’s domestic semiconductor industry remains restricted to antiquated nodes, resulting in a structural bottleneck that will take time to overcome.

Radar systems rely on single-source beryllium ceramics from Kazakhstan and high-frequency PCB laminates manufactured in the United States, often routed via third nations. Western software and testing equipment play a major role in system design, simulation, and calibration. Taken together, this implies that supply-chain disruption, export restrictions, and sanctions can weaken Russia’s air defence without resorting to kinetic force. The lesson is clear: air defence fails at the manufacturing level as well as in the air. India is directly affected by this caution.

| Core Element | Dependency | Hidden Vulnerability | Strategic Implication |

| Command & Control (S-400) | Foreign-fabricated processors (Elbrus-90micro) | Domestic fabs stuck at outdated nodes | Production and upgrades can be externally throttled |

| Radar Materials | Single-source beryllium ceramics; US PCB laminates | No rapid substitutes available | Radar performance collapses under supply denial |

| Design & Simulation | Western EDA software | Sanctions restrict modernisation | Innovation halts without access to tools |

| Testing & Calibration | Foreign equipment | Wartime maintenance delays | Readiness erodes without combat |

| Overall Ecosystem | Globalised supply chains | Sanctions and export controls | Air defence can fail industrially, not tactically |

India’s Reflection in the Russian Mirror

Not only is India developing a layered defence infrastructure composed of Russian, Israeli, French, and American systems, but they are using the same S-400 systems that are being investigated by the RUSI inquiry. While it is advantageous that India is not dependent on a single nation, given the diversity of its suppliers, this diversification does not eliminate vulnerability. On the contrary, India is accumulating multiple vulnerabilities that extend from radar and missiles to microelectronic chips, software, and specialised materials.

Precision machine systems, radar materials, test facilities, or electronic design capabilities sourced from other nations remain indispensable, even for ostensibly indigenous development. As a result, sovereignty is often limited to assembly or subsystem level development, while critical upstream and downstream layers remain under external control. India’s defence sovereignty is, therefore, conditional, particularly in the face of non-kinetic forces such as sanctions, export controls, etc. Hence, self-reliance in defence is a strategic necessity for engaging in war efforts, not mere slogans.

A country must own the entire chain, from semiconductors and sensors to missiles, software and certification, if it is to credibly claim air defence independence. This principle is partially realised in Indian programmes such as Akash, Akashteer, Uttam AESA, Tejas, and AMCA. At present, however, scale and depth rather than conceptual capability remain the primary constraints. One is left with no option but to learn from Russia.

Operational Risks and Strategic Path Forward

A factor that makes India vulnerable during war is its dependence upon imported air defence systems. In modern warfare, intercept missiles get exhausted quickly, and it is apparent that Russia has struggled to replenish such missiles at scale. In an India-China or India-Pakistan war, the imported S-400 or Barak-8 missiles could be depleted within weeks.

Furthermore, imported systems often function as “black boxes,” making it extremely difficult, if not impossible, to modify the seekers to counter drone swarms and saturation attacks, modify algorithms, or evade new approaches related to electronic warfare. This constraint would leave Indian forces reactive, rather than adaptive, on the battlefield.

“Geopolitical grip” is the factor that multiplies the dangers of any lack of preparedness by causing restrictions, delays in delivery, or limited information. Furthermore, “proprietary architectures” pose dangers by means of seams that destroy the air photo.

Accordingly, India’s air defence posture should adopt a strategy of progressive self-reliance. In the coming years, this would require a systematic dependency audit to identify critical interceptors. Focal points of medium-term priorities would be domestic semiconductors, radar materials, design software, or deeper private sector integration, while long-term goals and objectives would encompass leadership roles in directed energy, electronic warfare, AI-enabled command and control, and globally export-capable industrial strengths. Air defence “independence” ultimately requires end-to-end control of the entire mission sequence from chips through sensors, through missiles, software, integration and certification.

Conclusion: Securing India’s Air Defence Sovereignty

A crucial lesson emerging from the RUSI report on Russian air defence is that even sophisticated systems can fail when they rely on brittle, external supply channels. Comparable concerns apply to India with respect to imported software, subsystems, and components in platforms like the S-400, which can lead to weaknesses in interceptor availability, software adaptability, integration, and geopolitical leverage.

Control over the entire operational chain, including microelectronics, radars, missile systems, command software, electronic warfare, and testing infrastructure, is necessary for achieving true air defence sovereignty. The capability is demonstrated by India’s domestic initiatives, such as Akash SAM, Akashteer, Uttam AESA Radar, Tejas, AMCA, and BrahMos, but these efforts must be scaled, integrated, and industrialised.

Operational preparedness, strategic autonomy, and robust national security can be ensured through a tiered, long-term strategy that combines dependence audits, sustained domestic manufacturing, and AI-enabled, layered air defence architectures.

Appendix 1: Pantsir-S2 Supply Chain

Appendix 2: The following references indicate Russian systems’ technological dependency on foreign-origin materials and infrastructure used in advanced radar and antenna systems.

Piyush Anand is a Biotechnology Engineering student at Chandigarh University. His primary interest lies in International Affairs, Defence and Strategy. Views expressed are the author’s own.