- The H1-B was the only legitimate visa that, until now, allowed for skilled immigration to the US at scale.

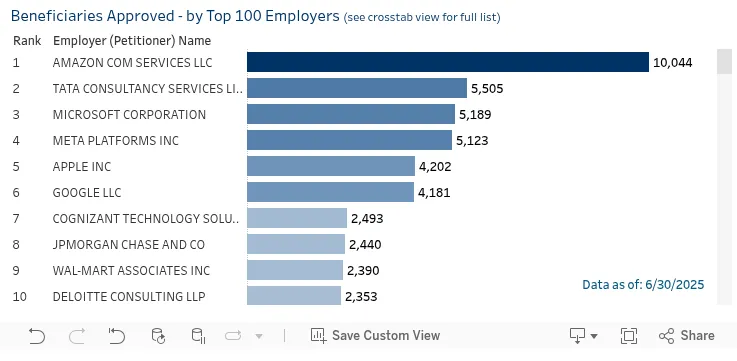

- In FY24, US Big Tech companies got more H-1B approvals than the top 7 Indian IT firms combined. Ironically, the policies aimed at protecting American jobs might end up pushing more high-value work out of the US.

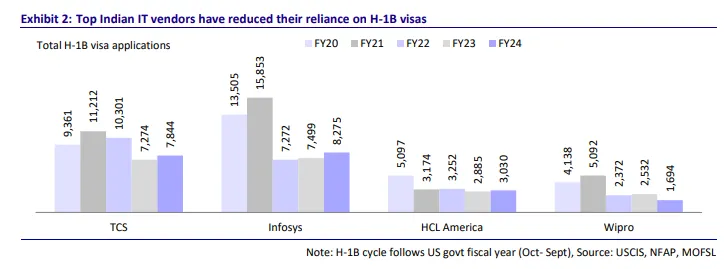

- During Trump’s presidency and the COVID-19 aftermath, soaring H-1B denials and long visa delays pushed Indian IT firms to reduce reliance on sending staff onsite.

- The H-1B’s new price tag may have priced out the Indian dream of reaching America, but it might just bring America’s work to India instead.

H-1B rules come for India’s IT industry

For the last couple of decades, Indians have had their own version of the American Dream. If you learnt your way around a computer and worked hard enough, someone would lay a path for you to American shores. It was the dream, finding an employer that would fund your visa, letting you live a life that only the world’s richest country could offer.

Last week, that dream took a terrible dent. The US has just hiked the one-time fee for all new petitions (but not renewals) of its most popular visa, the H-1B, from approximately $2,000 to $5,000 to a staggering $100,000. Suddenly, simply trying to get to the US costs almost a crore.

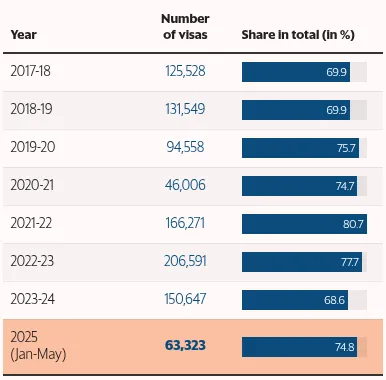

Nobody is as badly hit by this as Indians: we make up roughly three of every four H1-B visas that are granted.

But this doesn’t just hit Indians’ dreams of a better life. They might hurt our domestic IT services firms. They are, after all, some of the biggest recipients of H-1Bs in the world, with business models that rely heavily on these visas.

This is hardly the first time that Indians have suffered a shock from US visa rules, though, and Indian IT knows this all too well. This is, more than anything, a story of how businesses adapt to geopolitical uncertainty.

Let’s dive in.

The onsite-offshore model

Why do our IT companies rely so much on the H-1B visa?

Well, companies like Wipro, Infosys and TCS make most of their revenue from American clients. Most of what they do can be done from anywhere in the world, but there are a few tasks, from understanding client workflows to maintaining critical systems, that require their physical presence. And so, these firms deploy a few software engineers to client sites in America.

For many Indians, this was one of the biggest perks of joining such a company. An Indian software engineer who earned ~$30,000 annually in Bengaluru could, perhaps, find the opportunity of being embedded at a Fortune 500 company in New York. Apart from the experience, it would also net them a salary bump for the higher cost of living.

The IT firm, meanwhile, would bill $150,000-200,000 per year to their client, a good profit on each employee they sent.

This is called the “onsite-offshore” model, and it brought fat margins for Indian IT firms. The onsite team made up only 20-30% of the project team, while the rest were based in India. This lets firms charge their clients hefty sums while paying relatively low labour costs for their Indian employees. Infosys, for instance, only has 3.3% of its employees on H-1B, but they generated 11.5% of the company’s revenue.

However, with the $100,000 fee, the economics of H-1B are completely broken. Unless you can see a profit per worker that is substantially above $100,000, there’s simply no point in attempting this route any more. This weakens the very foundation of the onsite-offsite model.

The Visa Maze –

What made the H1-B so critical?

After all, the H1-B had its problems. Your visa had to be sponsored by an employer, who would have to pay as much as $5,000 to get you through. There was a cap on how many of them could be given out, and if there were more applicants than the limit, you’d have to win a lottery to get one.

But as we shall see, it’s better than the alternatives.

The first alternative is the L-1 visa, which allows for transfers within a company. It has no cap or lottery, unlike the H1-B. However, there’s a catch: the visa only allows staff who have specialised knowledge of how their company works, and should be directly supervised by the US arm of their employer.

By the very nature of their work, Indian IT onsite employees don’t fulfil either condition. Indian IT firms have tried to illicitly use the L-1 as a substitute for the H-1B, a strategy called “body-shopping”, where generic programmers were tried to be passed off as having specialised knowledge. But that backfired spectacularly. Between 2012 and 14, for instance, 56% of all Indian L-1 visa petitions were declined to clamp down on body-shopping.

Then, there are B-1 visas for business visitors. These are supposed to be temporary, meant for attending conferences or meetings that last a few days. Indian IT tried using B-1 visas to circumvent the caps of H-1B visas, only to learn, the hard way, that this was considered fraud. In 2013, for instance, Infosys paid a whopping $34 million settlement after being found they have illegally used B-1 visas for onsite workers.

Lastly, there are O-1 visas, which actually have high approval rates and no annual cap. But they’re reserved for genuine stars, think acclaimed researchers or award-winners. The average Indian software engineer hardly fits here.

The H1-B was the only legitimate visa that, until now, allowed for skilled immigration to the US at scale. You could relocate a generic worker, without special knowledge or genius, for up to six years. It was the only way the labour arbitrage model of an IT company made sense. They could sponsor thousands of H-1Bs every year while yielding good returns.

The Great Pivot

But does this simply rip apart the business of our IT industry? Not really. This isn’t their first rodeo. They’ve been here before and are prepared.

US immigration policy, after all, has often been volatile. After 9/11, for instance, US visa issuance slowed down because of heightened security concerns. In 2009, the US implemented the “Employ American Workers Act”, which cracked down on outsourcing by making H-1Bs stricter. Under Trump’s first presidency in 2017, H-1B denial rates skyrocketed from 6% in 2015 to 24% in 2018. Then, after the COVID-19 pandemic, Indians would regularly have to wait for more than two years just to secure a visa appointment.

Which is why, over the last few years, Indian IT firms have consciously decided to decrease reliance on staffing Indians on-site. Instead, they either hire locals in the US or convince the client to offshore more of their work to India.

This strategy has yielded solid results. Infosys’s onsite staff on H-1B visas dropped from 30% a few years ago to 24% in FY25. 80% of HCL’s US workforce is now local hires, up from 70% a few years ago. Industry-wide, H-1B holders now make up just 3-5% of total headcount, versus well above 10% a decade ago.

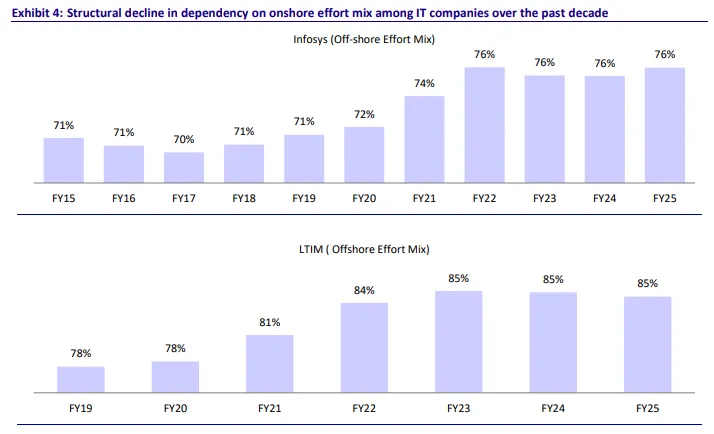

Meanwhile, more client work is also being moved offshore. For some companies, what used to be a 70:30 offshore-to-onsite split has shifted closer to 80:20 or even higher.

And finally, India’s IT industry is also trying to diversify into regions other than the US, where its business model might have more stability.

Potential impact on margins

That said, what does this mean for the companies’ numbers?

Obviously, Indian IT won’t continue making the same number of applications, bearing the full cost burden of all of them. They’ll begin rationing visa applications where it really makes sense. Because of this, many analysts expect the margin hit from new visa applications (due FY27) to be fairly low- 0.5-6% of the projected profit-after-tax in FY27. Companies may have to incur slightly higher costs for future visas, but it shouldn’t be something they can’t bear.

In fact, this could even be a net positive, primarily owing to offshoring more of the client work. CP Gurnani, the former CEO of Tech Mahindra, has said:

“We will do more offshoring, there will be more global capability centres (GCCs), and there will be more automation.”

But there will be some companies that’ll have to seriously rethink how they do business. Analysts from CLSA, for instance, point out that mid-cap companies like LTIMindtree and Persistent Systems are more exposed than the largest IT companies, as they’re more reliant on earnings from H-1B staff than large firms. While those workers who already have a visa will be unaffected, it’ll be hard to send new workers to the United States. These companies will have to plan accordingly.

GCCs to the rescue

There’s another side to India’s outsourcing story: global capability centres (GCCs). Indian IT companies aren’t actually the biggest H-1B users anymore. In FY24, US Big Tech companies got more H-1B approvals than the top 7 Indian IT firms combined. They, more than IT companies, might see their operations disrupted by Trump’s new policy.

But there’s a difference.

Unlike Indian IT firms, the Indian arms of GCCs don’t work for third-party clients; they build products of their own. MNCs create GCCs in countries like India to take advantage of lower labour costs and have them do low-value work. However, over time, these GCCs are increasingly doing more high-value tasks like R&D, becoming key hubs for MNCs.

Now, here’s the thing: US-based firms use H-1Bs to transfer talent from their Indian GCCs to headquarters. This lets them source top performers from a large pool of solid, cost-efficient tech talent. What does the $100,000 fee do to this?

There’s no way to know for sure. But as a recent Times of India article argues, the $100,000 fee might just accelerate this boom. If it costs six figures to bring a talented engineer from Bengaluru to Seattle, might it make better sense to hire more engineers in Bengaluru and move all the work there instead? Unlike Indian IT, there are no contracts on the line. An inability to export people doesn’t put contracts at risk. To them, it’s purely a cost proposition. And if it becomes much harder to bring workers to the US, the economics might just favour a new India office.

The irony is palpable: policies aimed at protecting American jobs might end up pushing more high-value work out of the US.

The New Reality

Maybe the new H-1B rules may not make much of a difference to the survival of the Indian IT industry.

It does, however, point to a darker geo-economic direction the United States wants to take, one where it tries to clamp down on services exports to the US altogether. At the same time as this clamp-down, the United States is also debating the HIRE Act, which, if implemented, will put a 25% duty on US companies that outsource jobs in tech. The US is, in a sense, trying to reverse the process of globalisation, keeping as much business as it can within its borders.

Can it succeed? We’re not sure. But it can do plenty of damage even if it fails.

That said, every crisis presents a hidden opportunity, and for all we know, this might be one for us. Indian IT knows, it seems, is already prepared for any eventuality, including changing its business model. Meanwhile, the government is already taking steps to ensure further support for our GCC ecosystem. The H-1B’s new price tag may have priced out the Indian dream of reaching America, but it might just bring America’s work to India instead.

Diksha Bharti is currently pursuing a Master’s program in Russian studies. She has previously worked as a Research Associate at Politika and the Consilium Research Institute. She has a keen interest in geopolitics and has contributed to several reputed platforms. Views expressed are the author’s own.