- India’s trade with Central Asia, standing at $2 billion in 2024, is targeted to reach $10 billion by 2030 through diversified sectors, currency swaps, and digital integration initiatives like UPI and India Stack.

- China’s dominance was formalised with the June 2025 Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighbourliness, which secures $94.8 billion in trade and embeds the Belt and Road Initiative under legal protections drawn from the UN Charter and SCO mechanisms.

- U.S. sanctions under the Iran Sanctions Act and CISADA continue to restrict India’s investment in Chabahar Port, though Trump 2.0 could restore exemptions through national-interest waivers under the NDAA.

- If India and the U.S. coordinate through IMEC and targeted sanction waivers while leveraging arbitration mechanisms like the ICC and PCA, they can counterbalance China’s BRI and revive Central Asia as a cooperative hub rather than a contested one.

Introduction

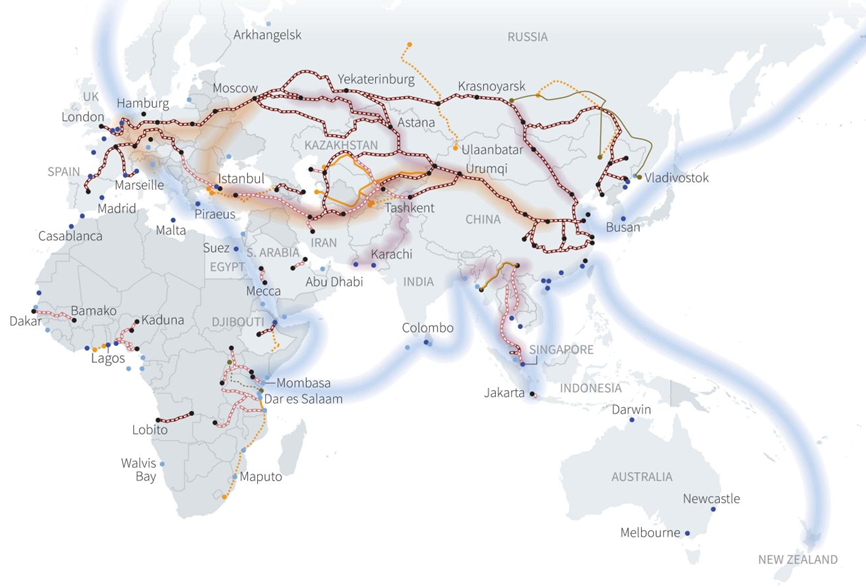

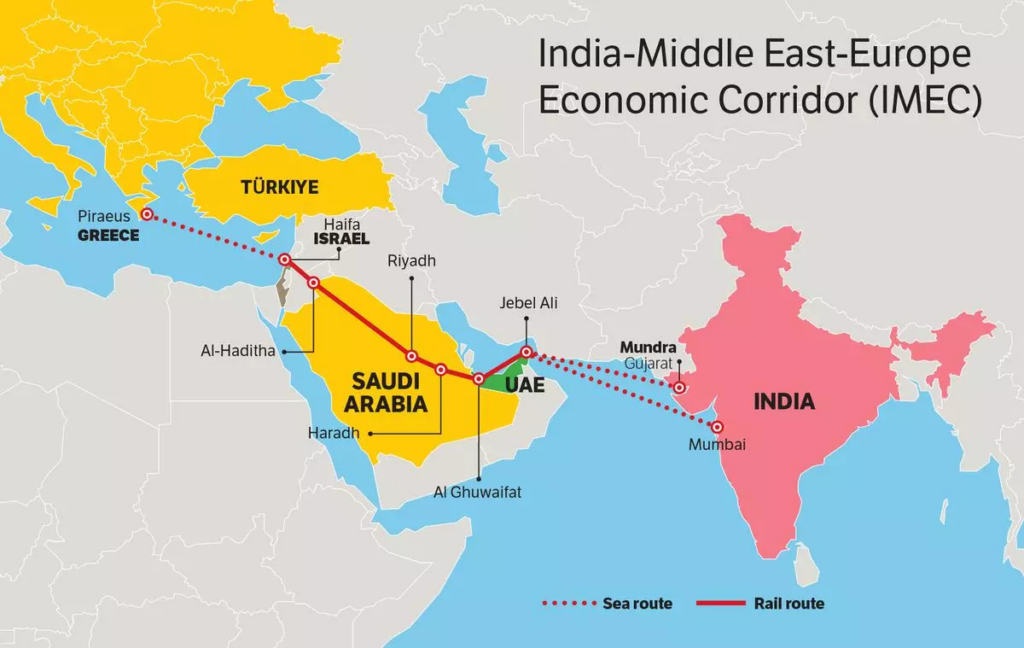

Both Dr Jaishankar’s thorough “4Cs” framework—Commerce, Connectivity, Capacity-building, and Contacts—and the larger legal and geopolitical struggle between rival connectivity initiatives have influenced India’s strategic engagement with Central Asia as it enters a pivotal phase. With projects like Chabahar Port, the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), and the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), India is an open and sovereignty-conscious partner. Meanwhile, China strengthened its position in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with the June 2025 ratification of the Treaty on Eternal GoGood-Neighbourliness. Regulatory pressures and U.S. sanctions regimes further complicate India’s outreach. Set against this, analysing Jaishankar’s approach coupled with the Middle Corridor legal frameworks, the BRI, the IMEC, and the Zangezur corridor illustrates how international law, arbitration measures, and sanctions exemptions will cut the difference between or if India succeeds in shoving $2 billion worth of trade with Central Asia to reach the lofty target of $10 billion by 2030.

India’s External Affairs Minister, Dr Jaishankar, has presented a clear and comprehensive plan for improving India-Central Asia relations as of September 26, 2025. The plan emphasises the region’s status as an “extended neighbourhood” with strong historical ties derived from shared Buddhist heritage, Mughal-era cultural exchanges, and ancient Silk Road trade. At the 4th India-Central Asia Dialogue, which took place in New Delhi on June 6, 2025, and was attended by the foreign ministers of Tajikistan (Sirojiddin Muhriddin), Kyrgyzstan (Zheenbek Kulubaev), Turkmenistan (Rashid Meredov), Kazakhstan (Murat Nurtleu), and Uzbekistan (Bakhtiyor Saidov), he provided his most comprehensive explanation in his opening remarks. An early look at these views was given by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI), which co-chaired the June 5, 2025, India-Central Asia Business Council (ICABC) conference.

Jaishankar stressed that bilateral trade, which is projected to reach $2 billion in 2024, is “far below potential” given the hydrocarbon, rare earth, and uranium reserves in Central Asia that are essential to India’s energy security. His “4Cs” framework—Commerce, Connectivity, Capacity-building, and Contacts—was first introduced in the 3rd Dialogue on December 19, 2021, and finalised on June 6, 2025. Its goal is to triple trade to $6 billion by 2030 through sectors like pharmaceuticals ($500 million in exports in 2024), IT services, agriculture, textiles, jewellery, and gems. He emphasised transparency, broad participation, local priorities, financial sustainability, and respect for sovereignty as guiding principles to counter opaque programs like China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) on June 5, 2025, at the ICABC.

Trade And Economic Diversification

On June 6, 2025, Jaishankar specified three concrete goals for the economic partnership: expanding the reach of the existing partnership, diversifying the trade basket to include products other than commodities such as cotton and hydrocarbons, and achieving “sustainability and predictability” so that geopolitics-related problems could be mminimised At the ICABC meeting on June 5, 2025, he gave a presentation on a “business-led roadmap” to enhance trade and investment. In order to reduce transaction costs by 15% by 2027, he called for the integration of India’s Unified Payments Interface (UPI) with digital platforms in Central Asia. He also called for the use of national currencies for mutual settlements, such as INR-tenge swaps with Kazakhstan and INR-som with Kyrgyzstan, to reduce dependency on the dollar by 20%.

Uzbekistan rolled out India’s Aadhaar-type system to 10,000 government employees under the “India Stack” e-governance platform, which was pilot-tested in the 1st India-Central Asia Digital Forum in Tashkent on May 15, 2025. Innovation and the digital economy are key areas.

In order to facilitate interbank agreements, the proposed Joint Working Group on Banking Linkages focused on financial services when it was announced on June 6, 2025. A $50 million trade finance Memorandum of Understanding was signed on June 5, 2025, between ICICI Bank and Halyk Bank of Kazakhstan. Jaishankar promoted the growth of pharmaceutical exports in the healthcare industry, citing the fact that India will provide $200 million worth of generic medications to Tajikistan and Uzbekistan by 2024.

Jaishankar’s “4Cs” framework—Commerce, Connectivity, Capacity-building, and Contacts—defines India’s approach to transforming Central Asia from a peripheral market into an “extended neighbourhood” central to its strategic outreach.

Additionally, starting in October 2025, he announced plans to expand the annual number of Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) training slots for Central Asian medical professionals from 500 to 1,000. Further, the 2nd India-Central Asia Rare Earth Forum (Almaty, October 10, 2025) saw significant minerals cooperation by mapping cooperative exploration of Kazakh uranium deposits and Tajik lithium reserves with the goal of $100 million in contracts. On June 5, 2025, Jaishankar deliberated $132 million in commerce between India and Uzbekistan in 2023–2024 during bilateral talks. This includes $20 million in Uzbek cotton and $10 million in dried fruits in return for $50 million in electronics and $30 million in textiles. He also commended Central Asia’s condemnation of the Pahalgam terror attack (April 22, 2025, 26 fatalities) in his remarks on June 6, 2025, stating that such solidarity “builds trust” for commercial transactions.

Connectivity And Infrastructure Initiatives

The lack of direct land borders, exacerbated by Pakistan’s refusal to permit overland access, is addressed by Jaishankar’s connectivity plan, which was unveiled on June 6, 2025, and makes use of multi-modal corridors. He referred to Iran’s Chabahar Port as a “game-changer,” reducing transit times from 45 days (via Suez) to 20 to 25 days and costs by 30%. India has also completed $120 million in Phase 2 investments, which include cranes and container-handling equipment delivered on August 15, 2025. In his June 5, 2025, ICABC speech, he praised Chabahar’s integration and welcomed Uzbekistan’s full membership (ratified June 14, 2025) and Turkmenistan’s upcoming accession (planned for December 15, 2025) to the 7,200-kilometre International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC).

Negotiated with Minister Nurtleu on June 5, 2025, Kazakhstan’s eastern INSTC branch aims to cut Mumbai-Moscow freight delays by 40%, with a pilot shipment of 500 tons of Indian textiles completed on July 20, 2025. In the context of the UNECE TIR Convention of 14 November 1975, the June 6, 2025, Joint Statement pledged to speed up building the 628-kilometre Chabahar-Zahedan rail link (to be finished by June 30, 2026, financed by India for $200 million) and increasing usage of TIR Carnets to 5 million carnets by the year 2027.

Citing the 1st India-Central Asia Joint Working Group on Chabahar (Mumbai, April 12–13, 2023), Jaishankar argued for a national interest waiver under NDAA Section 1245(d)(4)(D) (2012) and proposed quarterly reviews starting in September 2025 to address U.S. sanctions under the Iran Sanctions Act (August 5, 1996).

Additionally, he promoted aviation connections by launching IndiGo’s direct flights to Tashkent (twice weekly starting November 1, 2025) and Almaty (weekly starting November 15, 2025) and marine links for Turkmenistan’s cargo via Chabahar, estimating 2.5 million TEUs annually by 2027. To provide economic predictability in an X post, he urged the ICABC to prioritise “streamlined transit procedures” on June 5, 2025.

Capacity-Building, Cultural, And Security Cooperation

Jaishankar highlighted “capacity enhancement” through the ITEC program on June 6, 2025, in response to Tajikistan’s Glacier Preservation Conference (June 10, 2025, Dushanbe). This program grants 1,500 scholarships and training slots for 2025-26 in AI, renewable energy (such as solar microgrids for rural Kyrgyzstan), and disaster management, which are connected to the Himalayan glaciers’ Five-Year Action Plan on Mountain Development (2023-27). He cited India’s 2024 training of 200 Tajik engineers for flood-resistant infrastructure as an example.

Through e-visas (which were introduced on July 1, 2025, and 5,000 of them were completed as of September 2025) and cultural activities like the India Rooms at National University, Tashkent (which was launched on March 15, 2025) and the Tagore statues in Ashgabat (which were inaugurated on October 10, 2022), he promoted people-to-people contact for “contacts” with a target to achieve 50,000 Central Asian visitors and students by 2026.

In terms of security, the June 6, 2025, Dialogue condemned the Pahalgam incident and promised to exchange intelligence via the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (SCO-RATS, established June 7, 2002), which managed 15 joint operations in 2024. During his June 6, 2025, broadcast, Jaishankar said “regional security and terrorism” talks are “key to forging a closer alliance.” He suggested training 100 security experts during the 2nd India-Central Asia Anti-Terrorism Workshop (Bishkek, January 2026). He also underlined India’s involvement in the SCO, of which it has been a full member since June 9, 2017, noting that the Tashkent conference on July 12, 2025, will function as a platform for collaboration on counterterrorism.

China’s BRI and the Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighbourliness

Competing connectivity efforts undertaken by India’s Modi 3.0 administration and the newly elected Trump 2.0 regime on September 26, 2025, reflect the strategic and economic importance of Central Asia and seek to upset China’s dominance over the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). At the second China-Central Asia Summit (June 16–18, 2025, Astana), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan signed the Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighbourliness, Friendship, and Cooperation on June 17, 2025, committing them to BRI projects such as the $8 billion China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, which is backed by $208.86 million in Chinese grants.

In accordance with the Shanghai Cooperation Organization’s (SCO) Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS, which was created on June 7, 2002, and the United Nations Charter’s Article 2(4) (territorial integrity) and Article 33(1) (peaceful dispute resolution), this agreement fortifies China’s $94.8 billion trade with Central Asia 2024.

At the same time, in a transaction-oriented strategy to confront Beijing, President Trump left early on June 16, 2025, from the G7 Summit in Kananaskis (June 15–17, 2025), even as Middle East tensions and his urging for Russia’s G8 reinstatement were still in progress. American sanctions through the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act (CISADA, Public Law 111-195, July 1, 2010) and the Iran Sanctions Act (Public Law 104-172, August 5, 1996) keep India from investing $500 million in Chabahar Port, which is vital to the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC, inaugurated on September 9, 2023).

Trade in the Middle Corridor is at risk due to Biden-era pressure on Georgia under the EU-Georgia Association Agreement (signed June 27, 2014), even though the Zangezur Corridor’s legal framework is based on the Tripartite Ceasefire Agreement (November 10, 2020, Clause 9). This section examines specific legal provisions, enforcement practices, and the roles of international organisations (SCO, WTO, ICC, OFAC) that oversee the BRI, IMEC, Middle Corridor, and Zangezur initiatives in order to balance strategic interests without ceding Central Asia to China. It argues that diplomatic mediation and targeted waivers of U.S. sanctions are crucial.

The Middle Corridor’s stability depends on reversing EU sanctions pressure on Georgia, aligning with WTO GATT Article V:2 to safeguard freedom of transit and sustain Euro-Asian trade routes.

China’s BRI dominance in Central Asia was formally stated at the second China-Central Asia Summit (June 16–18, 2025), which expanded on the ideas of universal security and mutual aid from the Xi’an Summit (May 18–19, 2023). The Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighbourliness, Friendship, and Cooperation (signed June 17, 2025) commits $208.86 million in Chinese grants for three cooperation centres (poverty reduction, education, and desertification control) in compliance with UN General Assembly Resolution 70/1 (September 25, 2015) on sustainable development. Cooperation in natural gas, minerals, and railway infrastructure is required by Article 3(1) of the treaty. Article 4(2) calls for coordinated efforts to combat cybercrime, drug trafficking, and cross-border terrorism. The SCO RATS protocols (June 7, 2002) made this operational, allowing for 127 joint operations in 2024.

Through the use of UN Charter Articles 2(4) (prohibiting territorial violations) and 33(1) (mandating negotiation or arbitration), the agreement guarantees legal protections for China’s $94.8 billion in commerce with Central Asia (2024), including Kazakhstan’s $18 billion exports and $15 billion imports. Article 12 of bilateral investment treaties (BITs), like the China-Kazakhstan BIT (August 10, 1992, amended June 10, 2016), protects investments.

The WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA, February 22, 2017, Article 7) simplifies customs; nevertheless, as noted in China-Measures Affecting Imports (DS565, 2020), imbalances in trade (e.g., Kyrgyzstan’s $5.4 billion imports against $123.6 million exports) can contravene WTO GATT Article I:1 (most-favoured-nation treatment). China’s National Security Law (July 1, 2015, Article 25) permits dual-use BRI projects. As was the case in China National Building Material Co. v. Tajikistan (ICC Case 20345, 2019), this enables the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs to review the projects in accordance with the Arms Trade Treaty (April 2, 2013, Article 7), with the potential for arbitration at the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC).

- India’s IMEC and U.S. Sanctions on Chabahar

India’s IMEC, which was introduced on September 9, 2023, during the G20 Summit, relies on Chabahar Port to gain access to Central Asia, despite stringent legal limitations imposed by U.S. sanctions. The Iran Sanctions Act (Public Law 104-172, August 5, 1996, Section 5(a)) and CISADA (Public Law 111-195, July 1, 2010, Section 102), which are described in 31 CFR Part 560.201 (prohibiting financial transactions), impose secondary sanctions on companies that deal with Iran’s Central Bank.

On September 15, 2025, the United States withdrew Chabahar’s waiver of sanctions under the Iran Freedom and Counter-Proliferation Act (IFCA, Public Law 112-239, January 2, 2013, Section 1247(a)) and Executive Order 13846 (August 6, 2018, Section 2) due to non-compliance with 31 CFR Part 560.206 (port-related transactions), stopping India’s $500 million investment in Shahid Beheshti Terminal.

This is against UNCLOS Article 125(1) (transit rights for landlocked states), according to Bolivia v. Chile (ICJ, October 1, 2018, para. 119). Therefore, as in Russia-Measures Affecting Transit (DS512, April 5, 2019), India may challenge sanctions at the WTO Dispute Settlement Body for violating GATT Article XXI(b)(iii) (security exceptions). The UN Panel of Experts on Iran noted 12 violations in 2024 and demanded compliance in line with UNSC Resolution 2231 (July 20, 2015, Annexe B).

Trump may restore Chabahar’s role by issuing a waiver under NDAA 2012 (Public Law 112-81, Section 1245(d)(4)(D)) for the national interest, as authorised on November 6, 2018, in compliance with UN General Assembly Resolution 70/1 (Goal 9). India joined the SCO on June 9, 2017, and through its Business Council, it fosters communication (Article 11, SCO Charter). However, as was the case in BNP Paribas v. U.S. (2014, $8.9 billion fine), OFAC’s Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) List carries the risk of penalising Indian businesses. As demonstrated in India v. Iran (PCA Case 2016-17, pending), disputes could be resolved by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) to guarantee IMEC’s legal sustainability.

- Middle Corridor and EU-Georgia Legal Framework

Based on the EU’s TRACECA Agreement (May 8, 1993), the Middle Corridor (Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, or TITR) facilitates $12 billion in trade between the EU and Central Asia by 2024, with 60% of that trade going through Georgia. The EU-Georgia Association Agreement (June 27, 2014, Title IV, Articles 77–149) governs the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) and requires compliance with Article 8(1) (democratic principles). Biden’s sanctions, which also involved visa restrictions on June 6, 2024, and the threat to withdraw DCFTA benefits under EU Council Regulation 833/2014 (July 31, 2014, Article 2, amended June 23, 2023), invoked Georgia’s “foreign agents” law (passed into effect May 28, 2024) as an infringement of Article 8(2) (rule of law). This destabilises TITR, according to the European Commission’s 2024 Report (October 30, 2024), which noted a 15% drop in transit volumes.

According to WTO GATT Article V:2 (freedom of transit), which was upheld in Russia-Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (DS512, April 5, 2019, para. 7.302), and the EU’s Global Gateway Initiative (December 1, 2021, Article 3), Trump’s potential reversal through the U.S. Trade Act of 1974 (Section 301, 19 U.S.C. §2411) could restore stability. The UNECE TIR Convention’s simplified customs procedures (November 14, 1975, Article 3) will be used to process 3.2 million TIR carnets in 2024. The ICC Arbitration Rules (2021), which were used in EU v. Russia (ICC Case 21587, 2020, energy transport), provide legal certainty even though the WTO Dispute Settlement Body may handle EU sanctions, such as in EU-Customs Measures (DS566, 2021).

- Zangezur Corridor and Regional Stability

According to the Tripartite Ceasefire Agreement (November 10, 2020, Clause 9), which mandates unblocked transport links, and the Armenia-Azerbaijan Peace Agreement (March 15, 2025), which gives Azerbaijan 99-year development rights for the TRIPP Route under UN Charter Article 2(1) (sovereignty), the Zangezur Corridor connects Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan via Armenia. The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs is in charge of overseeing border demarcation, which is guaranteed by the ICJ’s interim rulings in Armenia v. Azerbaijan (December 7, 2021, para. 54). The EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP, May 7, 2009, Article 5) took the place of the OSCE Minsk Group (dissolved February 15, 2025) to facilitate mediation.

Iran’s objection was raised at the SCO’s Tashkent conference on July 12, 2025, citing the SCO Charter (June 7, 2002, Article 4(3)) on regional stability. This puts Iran at risk of being investigated by the ICC for potential war crimes under the 1949, article 3 Geneva Conventions, as was the case in Prosecutor v. Tadić (ICTY, 1995). According to UN General Assembly Resolution 68/262 (March 27, 2014), Trump’s mediation avoids conflict, but PCA arbitration upholds transit rights (e.g., Nicaragua v. Costa Rica, 2015, PCA Case 2010-01). The UN Security Council could employ Chapter VII sanctions for violations to guarantee adherence.

Conclusion

As of September 26, 2025, Jaishankar’s views, expressed at the 4th India-Central Asia Dialogue on June 6, 2025, and the ICABC on June 5, 2025, present India as a strategic partner that will leverage INSTC and Chabahar to boost trade from $2 billion in 2024 to $10 billion in 2030. His focus on diversified industries (pharmaceuticals, IT, minerals), currency exchanges, digital integration, ITEC training, and cultural exchanges, and open, sovereignty-respecting efforts, balances the hegemony of the Belt and Road Initiative. Previous criticism of American sanctions aside, Jaishankar’s proposal of quarterly Chabahar reviews and security coordination through SCO-RATS indicates the pragmatic intent of “taking ties to the next level,” said on June 5, 2025.

Commercial ties in Central Asia hinge on certain legal clauses to challenge China’s Belt and Road Initiative on September 26, 2025. The Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighbourliness (June 17, 2025, Article 3(1)) locks in $94.8 billion in trade under the SCO and UN Charter supervision, while UNCITRAL and ICC arbitration lower risks. Chabahar is prohibited by U.S. sanctions under CISADA (Section 102) and IFCA (Section 1247) in accordance with UNCLOS Article 125(1) and WTO GATT Article XXI; however, IMEC may be opened by NDAA Section 1245(d)(4)(D) waivers. To maintain trade in the Middle Corridor, as required by the EU-Georgia DCFTA (Article 8), Trump must undo the limitations imposed by EU Regulation 833/2014, in accordance with GATT Article V:2. The Zangezur Corridor benefits from PCA and ICC enforcement, as stated in UN Charter Article 2(1) and Clause 9 (2020). To prevent China’s overland routes from undermining U.S. influence over Iran and the Malacca Strait policies, the UN, SCO, WTO, OFAC, and ICC must prioritise arbitration. Modi’s IMEC and Trump’s deal-making can restore Central Asia as a hub for cooperation if stringent regulation is balanced with legal flexibility.

References:

- Wallerstein, I. (Ed.). (2023). Special issue: The legacies. Journal of World-Systems Research, 29(2). http://jwsr.pitt.edu/ojs/jwsr/issue/view/84

- Ministry of External Affairs. (2025, June 6). Joint statement of 4tthe h India-Central Asia Dialogue. Government of India. https://mea.gov.in

- Ministry of External Affairs. (2025, June 6). Opening remarks by EAM Dr Jaishankar at the India-Central Asia Dialogue. Government of India. https://mea.gov.in

- Embassy of India, Astana. (2025). 4th India-Central Asia Dialogue 2025 – Events/Photo Gallery. Embassy of India, Astana. https://indembastana.gov.in

- Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. (2025, June 6). Press release: 4th India-Central Asia Dialogue.

- Indian Technical and Economic Cooperation (ITEC) Programme. (2025). Annual programme report 2024–25.

- National Payments Corporation of India. (2025). Unified Payments Interface integration documents.

- ICICI Bank & Halyk Bank. (2025, June 5). Memorandum of Understanding for trade finance.

- Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India. (2025). Trade figures, export statistics, and annual reports.

- Republic of Uzbekistan. (2025, May 15). Digital Forum Tashkent proceedings.

- Jaishankar, S. (2025, June 5–6). Speeches and remarks at ICABC and 4th India-Central Asia Dialogue.

- Charter of the United Nations. (1945). 1 U.N.T.S. XVI.

- Treaty on Eternal Good-Neighbourliness, Friendship, and Cooperation (Central Asian States & China, 2025). Signed June 17, 2025, Astana.

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). (1947, October 30). 55 U.N.T.S. 194.

- World Trade Organization. (2017). Trade Facilitation Agreement (WT/L/940).

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization. (2002). Charter of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Signed June 7, 2002, entered into force September 19, 2003, 2235 U.N.T.S. 79.

- UNECE Convention on International Transport of Goods Under Cover of TIR Carnets (TIR Convention). (1975, November 14). 1079 U.N.T.S. 89.

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). (1982, December 10). 1833 U.N.T.S. 397.

- Arms Trade Treaty. (2013, April 2). 3013 U.N.T.S. 107.

- European Union–Georgia Association Agreement. (2014). OJ L261/4.

- Tripartite Ceasefire Agreement (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Russia, 2020). Signed November 10, 2020.

- Eastern Partnership Joint Declaration. (2009, May 7).

- United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development (A/RES/70/1).

- European Commission. (2024). Georgia: 2024 report (SWD/2024/613 final).

- United Nations Security Council. (2015). Resolution 2231 (S/RES/2231).

- United Nations General Assembly. (2014). Resolution 68/262: Territorial integrity of Ukraine (A/RES/68/262).

- International Committee of the Red Cross. (1949). Geneva Conventions. 75 U.N.T.S. 287.

- Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI). (2025, June 5–6). ICABC briefing document.

- Shanghai Cooperation Organization. (2025, June 6). Joint Statement: 4th India-Central Asia Dialogue, New Delhi.

Dr. Lakshmi Karlekar is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Humanities – Political Science and International Relations, Ramaiah College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Bengaluru. She holds a PhD in International Studies from CHRIST (Deemed to be) University. Tanishaa Pandey is a BBA LLB student at the School of Law, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Central Campus, Bengaluru. Views expressed are the author’s own.