- The U.S. sent the individuals convicted of serious crimes, including murder and child rape, to a third country, Eswatini, as their home countries refused to accept them.

- Reports suggest that Eswatini accepted the convicted individuals after promises of economic assistance or political support.

- The U.S. faces an ethical dilemma in balancing its imperative to protect national security with its obligation to uphold international human rights norms.

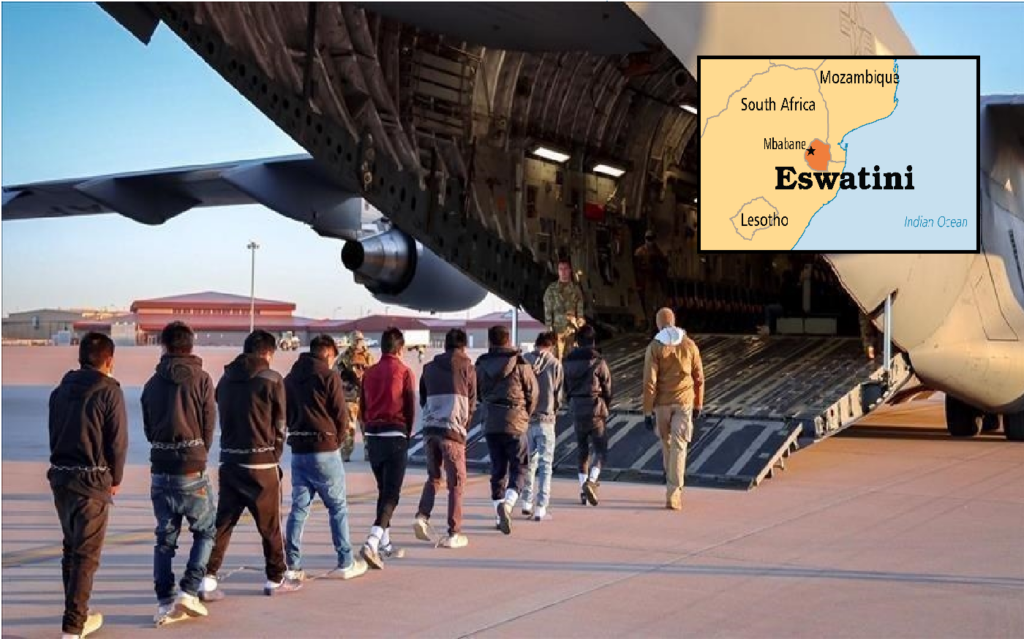

Recently, the U.S. deported five foreign nationals to Eswatini, people originally from Vietnam, Jamaica, Laos, Cuba, and Yemen, under a third-country deportation policy. These individuals were convicted of serious crimes, including murder and child rape, but their home countries refused to accept them back. As a result, the U.S. sent them to a third country, Eswatini, after a Supreme Court decision allowed such deportations on short notice. This development is highly complex, and this article analyses the issue from different angles: legal, humanitarian, political, and strategic.

Legal and Human Rights Concerns

One of the biggest concerns raised by rights groups is whether this action violates international law. The principle of non-refoulement, a core element of international refugee and human rights law, prohibits sending someone to a country where they are likely to face torture or persecution. Eswatini has a record of political repression, weak judicial independence, and detentions without trial. While the U.S. government claims that the men will not be persecuted, human rights activists argue that just having a “pledge” from Eswatini is not enough. There are no international monitoring mechanisms in place to guarantee their safety.

Moreover, the deportations were done without sufficient legal notice, sometimes with just six hours of warning. That raises due process concerns. Every individual has the right to appeal or challenge such deportations, especially when being sent to a country that is not their own.

Why Eswatini?

It’s also important to ask: Why Eswatini? The country has no direct connection with these individuals in terms of nationality or heritage. This arrangement seems to be based on behind-the-scenes diplomatic deals. Reports suggest that Eswatini accepted the individuals after promises of economic assistance or political support. If that’s the case, it turns the deportation process into transactional diplomacy, a troubling precedent.

Eswatini’s government has claimed that the five men are held in isolated custody and will eventually be repatriated. But that doesn’t clarify how long they will be held, under what laws, or whether they will get access to lawyers or fair treatment.

Domestic and Political Context in the U.S.

This deportation move fits into a broader Trump-era policy of strict immigration enforcement. The Supreme Court recently ruled that such deportations are legal, even without prior notification, as long as the receiving country agrees not to harm the individual. The ruling gives the executive branch vast power but has divided public opinion.

Supporters of the policy argue that dangerous criminals should not remain in the U.S. if their home countries refuse to take them. But critics ask: Is sending them to a completely unrelated third country fair? Does that solve the problem or just move it?

Conclusion: What’s the Way Forward?

This case shows the ethical dilemma between national security and human rights. Yes, the U.S. must protect its people, but it must also follow international norms. Deporting people to third countries with poor human rights records may seem like a short-term fix, but it sets a worrying trend.

A more transparent, accountable process is urgently needed. There should be international monitoring, clear legal safeguards, and fairer burden-sharing among countries. The world cannot afford a future where vulnerable individuals are traded like unwanted goods between nations.

References:

- AP News. (2025, July 16). Military exercises drawing together 19 nations and 35,000 forces begin in Australia.

- Human Rights Watch. (2024). World Report 2024: Eswatini.

- The Washington Post. (2025, July 16). U.S. sends five men to Eswatini amid Trump’s third-country deportations.

- UNHCR. (2023). The principle of non-refoulement under international human rights law.

- U.S. Supreme Court. (2025). Doe v. Department of Homeland Security, 598 U.S. (2025).

Sakshi Yadav is pursuing a Master’s Degree in International Studies from Christ University, Bangalore. Her research areas include International Political Economy, South Asia, South Pacific and U.S. Foreign Policy. Views expressed are the author’s own.