- Defence budgets are not merely fiscal submissions; rather, they are strategic signals that depict security challenges faced by states, their economic means, and international aspirations.

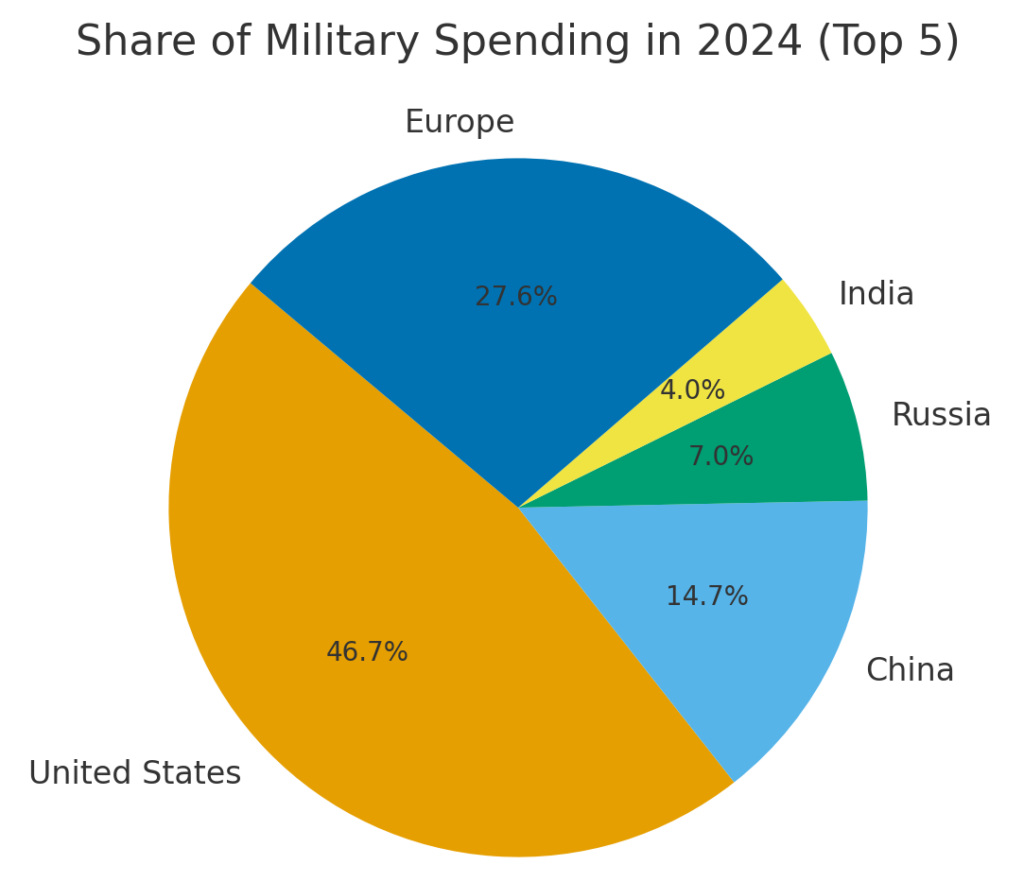

- The asymmetry is stark, with the system being multipolar in terms of actors but unipolar with the United States providing overwhelming leadership in absolute capability.

- Collectively, these trends are aspects of a multipolar order, but some asymmetries create instability and challenges to arms control.

- These cascades across the region show how the rise of one state leads to reactions elsewhere, demonstrating systematic cycles of militarisation.

Introduction

From 2010 to 2024, the period characterised by intense geopolitical instability, there has been a dramatic increase in world military spending. Defence budgets are not merely fiscal submissions; rather, they are strategic signals that depict security challenges faced by states, their economic means, and international aspirations. Within these fifteen years, several key events have transformed the international system politically: the rise of China, the assertiveness of Russia, the continued leadership of the U.S. in the world, and the resurgence of NATO and Europe post-2022 after the invasion of Ukraine, coupled with the slow emergence of India as a regional power.

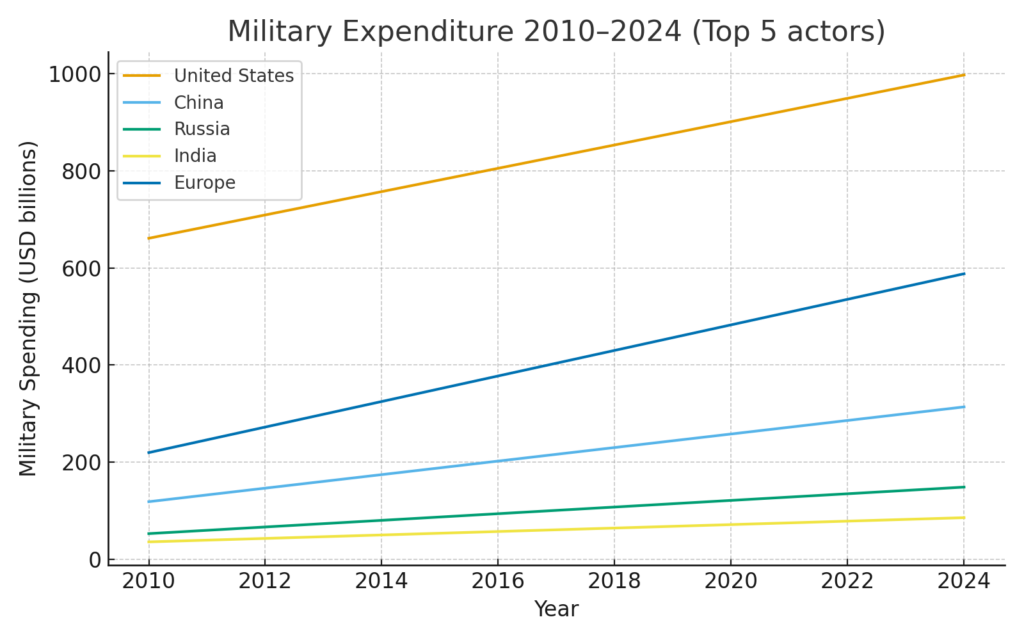

These changes speak to the advent of a more multipolar, complex system, with military strength still being one of the major currencies of influence. The present paper uses SIPRI’s Military Expenditure Database and analyses the expenditure trends of the top five actors- the U.S.A., China, Russia, India, and Europe- and interprets what these financial trajectories reveal about deeper geopolitical dynamics. The charts and data analyses provide empirical evidence in support of the argument that defence spending trends are shaped by and mutually inculcate strategic rivalry, alliance commitments, and security anxieties.

Military Expenditure Trends (2010–2024)

The pattern of expenditure from 2000 to 2014 seems to be one of long continuities punctuated by sudden discontinuities. As the figure shows, the United States has persistently remained the largest spender of all countries: starting from more than US$660 billion in 2010 and reaching almost US$1 trillion in the year 2024. On the other hand, China has seen the greatest absolute increase, having doubled its war budget from just under US$119 billion in 2010 to over US$300 billion in 2024. Russia and India, which start out from a less influential position, have also maintained consistent increases, the Russian spike after 2014 following its programmes for defence modernisation and wartime expenditure in Ukraine. Europe, taken as a whole here, had only moderate growth until 2021, when the invasion of Ukraine rapidly kick-started its rearmament. This again proves that crises are engines of defence spending.

Europe, taken as a whole here, had only moderate growth until 2021, when the invasion of Ukraine rapidly kick-started its rearmament. This again proves that crises are engines of defence spending.

Military Burden (% of GDP)

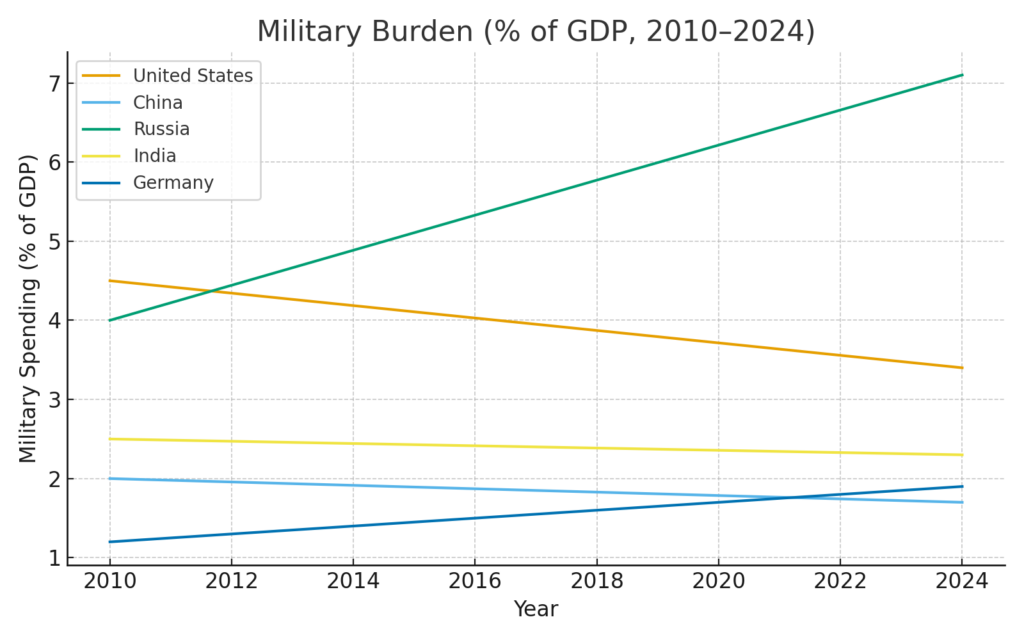

A total spending figure will define economic magnitude; the military burden is the weight of prioritisation and pressure: that is, what percentage of GDP an economy chooses to spend on defence. Russia is the exception: starting from 4% or so in 2010, its burden rose above 7% by 2024, a figure that derides Cold War mobilisation. Unconstitutionally dismissing the American value in absolute spending according to economic growth and slow drawdown of huge expenditures in Iraq and Afghanistan, the United States also saw a fall in burden from roughly 4.5% in 2010 to 3.4% by 2024. From a slight decline in the burden and increasing GDP faster than the defence budgets, the first thing is China’s defence spending levels in absolute terms. India maintained levels fairly consistently relative to nominal GDP of 2.3–2.5% while the German burden plumped massively post-2021 as the start of further German and European strategic assertiveness.

Global Distribution of Military Expenditure (2024)

About one-third of world defence spending comes from the United States. China’s share of around 12% is symbolic of its economic development and military modernisation. Europe, on the other hand, contributes more than 20% of the world’s defence expenditure, wartime Russia stands at around 5%, while steady India has a 3% share. The asymmetry is stark, with the system being multipolar in terms of actors but unipolar with the United States providing overwhelming leadership in absolute capability.

Drivers of Growth

By far, the structural and short-term drivers characterise increased military spending globally. First is the resurgent great-power rivalry, especially between the United States and China, prompting both powers to focus on developing naval, aeronautical, and cyber capabilities. Second, the ongoing war: the Russian war against Ukraine has forced Moscow itself to speed up defence expenditure commitments and the NATO members. Third, in their own way, technology increases costs: exo-atmospheric interceptors, hypersonic missiles, missile defence technologies, and space capabilities now cost a hell of a lot more than older generations of equipment. And finally, industrial policy — competition to defend supply chains and promote home production — forces countries to pour ever more money into ensuring sovereignty and resilience.

Geopolitical Implications

The geopolitical implications of such budgetary trends are enhanced. For the United States, almost a trillion dollars of defence spending enhances its capacity for global power projection and alliance leadership. China’s rapid growth signifies a regional power change that is already apparent in the Indo-Pacific region, where maritime disputes are becoming more contentious. Russia’s heavy burden signifies its attempt to retain great power status through hard military power, even with some economic costs. Europe is demonstrating new resolve, supporting NATO and moving away from decades of strategic lethargy. India’s slow climb may highlight its dual goal of balancing China and projecting leadership in the Global South. Collectively, these trends are aspects of a multipolar order, but some asymmetries create instability and challenges to arms control.

Regional Dynamics

The 2022 incursion of Ukraine altered the course of many policies in Europe. NATO defence budgets increased significantly, and Germany committed to exceeding a 2% of GDP threshold. Eastern European countries, either NATO or partner nations, are committed to some of the highest relative spending in the Alliance. In Asia, the growing modernisation of China was impacting regional arms buying—Japan was setting record budgets and Australia was showing further alignment with the U.S. and UK to integrate their armed forces, and action, more through AUKUS. In South Asia, India’s budget growth was matched by Pakistan’s determined efforts to sustain deterrence. The Middle East was seeing budget increases as well, as the Gulf States were spending on sophisticated systems even with regional tensions. These cascades across the region show how the rise of one state leads to reactions elsewhere, demonstrating systematic cycles of militarisation.

Economic Trade-offs

A high burden of military spending has opportunity costs. Russia’s commitment to military spending at 7% of GDP may be further burdensome on its economy, given the sanctions placed upon it, but as military spending increases even in the face of rising opportunity costs, they are allocating resources towards military achievements that will not be available for social spending. The United States’ challenge seems to be how to find a balance between military spending, infrastructure renewal, and social program funding. China is struggling with how to continue to manage economic growth while modernising its military. Democratic governments must continually scapegoat military expenses for their citizens, while authoritarian regimes are less concerned about domestic pain from their military spending. Overall, the consideration of these factors does not simply reveal a tension between security and other development aspirations, but a battlefield where, at least, a conflict over priorities can be observed.

Ultimately, choices reflect budgets: Where money is spent illustrates priorities.

Industrial and Technological Dimensions

Monetary expenditure alone does not build a defence capability; critically important is the structure of budgets and their purpose. The U.S. spends vast amounts of money on R&D, and currently retains superiority in stealth, space, and the application of AI. China is progressing in high-tech areas, but is building naval vessels and triggering missile forces. Russia has prioritised munitions and ground forces over modernisation at wartime. Europe has prioritised interoperability and replenished stockpiles. India wants to produce indigenously and diminish imports. The industrial bases built by these budgets are going to determine not only the military outcomes, but also the economic avenues in the subordinate fields.

Historical Comparisons

When compared to previous eras, today’s trends exhibit both change and continuity. U.S. and Soviet military budgets were larger percentages of GDP during the Cold War because of the bipolar nature of the system. Now with multipolarity, the costs are spread among multiple players. The U.S. remains a predominant spending power, but is not the unilateral hegemon of the past decades to the same extent. Complicated factors such as technology diffusion, defence supply chain globalisation, and emerging regional powers add complexity. The point is that while military spending continues to be a prominent indicator of power, the various forms of allocation of spending today mean that strategic calculations for military spending are more difficult than they were in the era of bipolarity.

Conclusion

Global military expenditures have shown an upward surge due to competition, conflict, and modernisation from 2010 to 2024. The United States still ranks No. 1 in terms of absolute spending. China, meanwhile, has risen to challenge the United States as a near-peer competitor; Russia operates under a heavy burden of a wartime economy; Europe has come back to the logic of deterrence; and India has affirmed its regional stature. Such has become a multipolar yet asymmetrical setting, with attendant opportunities for cooperative security arrangements as well as potential for instability. Ultimately, choices reflect budgets: Where money is spent illustrates priorities. To make a difference in trends, apart from actual budget allocations, this social exercise will demand a great deal of political vision to avoid an arms race threatening global stability.

Datasets:

- SIPRI Military Expenditure Database (2010–2024) – Stockholm International Peace Research Institute: https://www.sipri.org/databases/milex

- SIPRI Yearbook (various years, 2010–2024). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- Moving on to NATO. Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2023). 2023. Public Diplomacy Division, NATO: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_218428.htm

- IISS (International Institute for Strategic Studies) (2024).The Military Balance 2024. Routledge.

- World Bank Data – Military expenditure (% of GDP), GDP (current US$): https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/MS.MIL.XPND.GD.ZS·

Divyanka Tandon holds an M.Tech in Data Analytics from BITS Pilani. With a strong foundation in technology and data interpretation, her work focuses on geopolitical risk analysis and writing articles that make sense of global and national data, trends, and their underlying causes. Views expressed are the author’s own.