- Operation Sindoor, India’s decisive military operation in a geopolitically sensitive region, epitomises this doctrine. It demonstrated that when vital national interests are at stake, India must act unilaterally, without seeking global approval or waiting for multilateral consensus.

- But this time, India did the unthinkable and stuck Pakistan in Punjab, its heartland, under the spectre of a possible nuclear retaliation. But one outcome of this strike is clear: Pakistan’s nuclear bluster/bluff has now been nullified.

- India has long championed strategic autonomy, dating back to Nehru’s Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Today, it translates into engaging Russia and the U.S., Israel and Iran, ASEAN and Africa—without becoming entangled in bloc politics.

- India’s place in the global order will be defined not by the approval of other nations, but by the clarity of its national interest and the decisiveness of its actions.

In international relations, there are no permanent friends or enemies—only permanent interests. This realist axiom underscores the idea that state behaviour is driven not by sentiment but by strategic necessity. In recent years, India’s foreign policy has matured into a realist framework, evident in its selective alignments, robust regional posture, and firm responses to crises. Operation Sindoor, India’s decisive military operation in a geopolitically sensitive region, epitomises this doctrine. It demonstrated that when vital national interests are at stake, India must act unilaterally, without seeking global approval or waiting for multilateral consensus.

Now some time has passed, this essay will explore the transactional nature of international partnerships, the strategic necessity of unilateralism, and the role of realist principles in India’s foreign policy, using Operation Sindoor as a case study. It draws on classical and modern realist thought, recent geopolitical developments, and India’s evolving doctrine of strategic autonomy.

Realism and the Transactional Nature of International Relations

Realism, a dominant school of thought in international relations, asserts that the international system is anarchic, that states are the primary actors, and that survival and power are their chief concerns¹. From Thucydides to Hans Morgenthau, realists have argued that moral considerations or shared values rarely constrain state behaviour. Cooperation exists, but only when it serves national interest.

This perspective is evident in the “transactional diplomacy” that has characterised much of 21st-century geopolitics. For example, the United States’ partnership with Saudi Arabia hinges on oil and arms, not democratic values. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) uses economic inducements/coercion to expand influence, often ignoring governance issues in recipient states. Even in alliances like NATO, considered a paragon of shared security, internal tensions over burden-sharing, strategic priorities, and political values show the limits of idealistic cooperation².

India, too, has faced this transactional reality. Despite its democratic credentials, its partnerships are often evaluated through the lens of utility. During crises—such as the 1998 nuclear tests, the abrogation of Article 370, or the Galwan standoff—India often found that its strategic partners hesitated to back it unequivocally. Friendships in geopolitics are contingent, not categorical.

In international relations, there are no permanent friends or enemies—only permanent interests.

Operation Sindoor: Unilateral Action in the National Interest

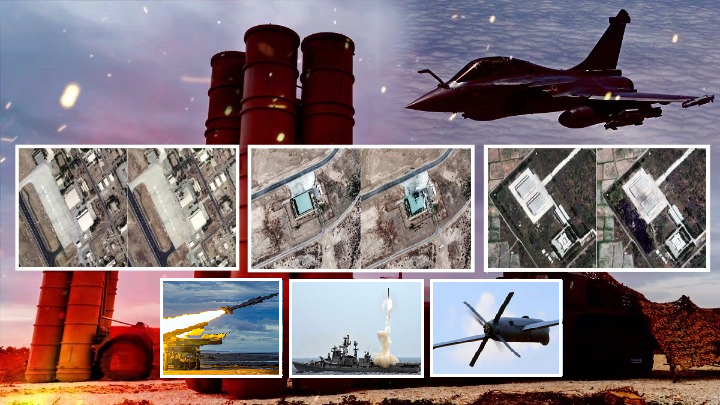

Though details of Operation Sindoor remain classified or selectively disclosed, credible reporting indicates it involved a combination of military posturing, civilian rescue, and proactive engagement in a volatile theatre. It also made it irreversibly clear India will act alone if it must, especially when the safety of its citizens, soldiers, or regional interests is on the line.

Four aspects of the operation Sindoor we must study.

- Unlike multilateral forums that are often bogged down by consensus-building, Operation Sindoor demonstrated swift and bold decision-making—a hallmark of sovereign assertion.

- Synchronicity between politico-military elements is crucial for effective governance and national security. It involves the alignment of political objectives with military strategy and operations, ensuring that the military acts by the will of the civilian government and India pulled it off seamlessly.

- While global opinion was cautiously neutral or ambiguous, India’s internal narrative was clear: the operation was necessary, justified, and within the norms of international law and for the first time, we got our Strategic Communication right.

- By refusing to wait for Western validation or UNSC sanction, India signalled that its rise will not be tethered to the approval of older powers, which is a clear geopolitical signal.

However, this is not the first time India has acted unilaterally. Operation Cactus (1988) in the Maldives stopped a coup attempt without waiting for international consultations. The Balakot airstrikes (2019) after Pulwama marked a doctrinal shift from strategic restraint to offensive deterrence³. But this time, we did the unthinkable and stuck Pakistan in Punjab, its heartland, under the spectre of a possible nuclear retaliation. But one outcome of this strike is clear: Pakistan’s nuclear bluster/bluff has now been nullified.

Why Are Partnerships Transactional?

International partnerships are formed based on converging interests, not emotional affinities. While diplomacy often involves symbolic gestures, actual cooperation hinges on what each party stands to gain. For example, the India–U.S. relationship, while strong in trade, defence, and tech, diverges on several fronts: human rights, climate responsibilities, or arms deals with Russia. India sees China as an existential threat; the U.S. sees it as a competitor. The alignment exists, but isn’t seamless.

Powerful nations often behave like transactional actors because they have leverage. China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea, Russia’s aggression in Ukraine, or America’s pivot to Asia are all examples of states adjusting partnerships for gain, not gratitude.

India’s history—the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War, where it acted decisively despite Western disapproval, or Pokhran-II nuclear tests, which brought global sanctions—shows that waiting for consensus can hinder national ambitions and growth.

S. Jaishankar, India’s External Affairs Minister, has argued in his book The India Way that nations must engage the world as it is—not as they wish it to be.

The Necessity of Unilateralism

Unilateral action, though criticised by multilateralists, is sometimes essential. International law allows states to defend themselves, secure their citizens, and protect vital interests. India’s recent posture reflects this understanding. India has long championed strategic autonomy, dating back to Nehru’s Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Today, it translates into engaging Russia and the U.S., Israel and Iran, ASEAN and Africa—without becoming entangled in bloc politics⁴. In the Indo-Pacific, India is part of QUAD with the U.S., Japan, and Australia—but it is not a military alliance. India resists formal entanglements, preferring flexible partnerships, and BRICS is a good example.

Realism and National Interest in Indian Thought

Indian thinkers have also emphasised realism. Kautilya’s Arthashastra teaches that statecraft involves deception, alliance-shifting, and power maximisation. B.R. Ambedkar, in his writings on defence and foreign policy, emphasised a strong, self-reliant military as essential for sovereignty⁵. S. Jaishankar, India’s current External Affairs Minister, has argued in his book The India Way that nations must engage the world as it is—not as they wish it to be⁶.

The best example is the 2016 Doklam standoff and 2020 Galwan clash with China, where we showed our resolve and did not back down, nor did we hope for global sympathy or support, as no one risked a confrontation with China. India knew it had to stand alone—militarily, diplomatically, and economically. Some argue that unilateralism undermines global norms and invites backlash, but when you are strong, the noise is just rhetoric and subterfuge.

Conclusion

India’s place in the global order will be defined not by the approval of other nations, but by the clarity of its national interest and the decisiveness of its actions. Operation Sindoor marks a new chapter in India’s assertive yet responsible foreign policy—one that combines realism with restraint, strategic autonomy with global engagement, and sovereignty with sensitivity. The fact is that every friendship between nation-states is transactional, and relationship dynamics change over time. In a multi-alignment multilateralist platform such as the United Nations often hides behind idolism and India must retain the right to act unilaterally—boldly, lawfully, and purposefully. That is the only way to ensure our security, sovereignty, and stature in the comity of nations.

References

- Morgenthau, H.J. Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace. New York: Knopf, 1948.

- Waltz, K. Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979.

- Pant, Harsh V. “The Balakot Strikes and India’s Shifting Strategic Doctrine.” Observer Research Foundation, 2019. https://www.orfonline.org

- Raja Mohan, C. “Strategic Autonomy 2.0.” Indian Express, 2020.

- Ambedkar, B.R. Thoughts on Defence and the Nation. Ed. Vasant Moon. Mumbai: Samyak Prakashan, 1997.

- Jaishankar, S. The India Way: Strategies for an Uncertain World. HarperCollins India, 2020.

Balaji is a freelance writer with an MA in History and Political science and has published articles on defence and strategic affairs and book reviews. He tweets @LaxmanShriram78. Views expressed are the author’s own.

Well-written article👏🏻👏🏻