The rise of coups across the globe seems unsettling. From South Sudan, Mali and Burkina Faso. From the Sahel region in Africa to the South American hub of coups, Venezuela. The globe seems to be ridden with the occasional military dictator laying claim to a province of land warranting no justification. Led on ethnicity, religion or a legitimate justifiable principle i.e. the motivation of the greater population to wrest power from a coercive state to itself.

Now, I 100% agree with your thoughts that this article stems from the recent coup in Bangladesh. The appropriate and broader motivation for this article is inclined towards understanding this – is there a possible set of ingredients that one finds themselves visiting before enacting a coup? And yes, you could call it reductionist but I’d call it being observant. There are stark reminders of previous coups, written in blood, sweat and tears. Forgetting them without extracting any meaning from them is a sin on our part.

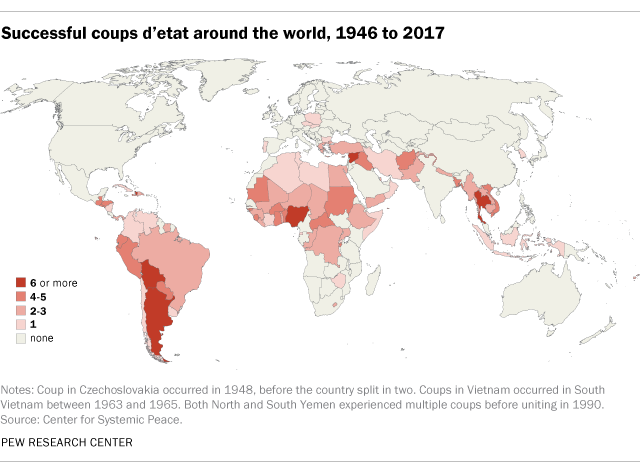

Now, let’s simply look at the number of coups ensuing across the globe.

The South American continent is ridden with coup attempts, and like a gradual serpent seems to wrap across the world. Now, prominent economists would deem that these countries primarily suffer an erosion of political institutions. In particular, Francis Fukuyama whose seminal work on state building in ‘The Origin of Political Order’ and ‘Political Order and Political Decay’, argues the cause of these repeated coups can be linked to a primary reason, political decay.

Political decay provides us with a rather interesting explanation for the rise of coups. Fledgling institutions that are incapable of adapting to the times now serve as a vent to direct people’s anger due to their incompetence. This can be either due to its problematic size, low productivity or a host of many reasons for which you could blame a firm’s incapability. The problem of Venezuela? That can be explained by its decaying justice system and the war of attrition waged by Nicholas Maduro on Venezuelan institutions, at a blitzkrieg pace which renders these institutions incapable of combating this barrage of attacks.

This provides us with our primordial root cause. Ideology. Bear in my mind, that the choice of words I make is deliberate. It is not the leader who the people are sold on, but instead, the ideology of either religious supremacy, ethnic purity or maybe milk before cornflakes that people are willing to consume. The leader might be quick-witted, humorous and electrifying in his tone. However, the ideology behind their wry smiles first puts them into power. However, let me be clear. I’m not indicating ideology to be something wary of. It’d be foolish of any of us to try and argue that ideology should always be labelled with a negative connotation. However, as Slavoj Zizek puts it – ideology is something that is far beyond perceptible and intelligibility. But to return to where we left off, the guiding ideology irrespective of its intention bears a clear emotion that reverberates across the economy intended to host a coup, resentment.

Resentment directed toward institutions is amplified by a growing population. First rippling through the younger population, poses an interesting question to ask as to why the students are always the first to protest. From Bangladesh to Tianmen, it’s clear that coups are always ignited by the embers of the young. Let’s take a deep breath now, so we’ve identified three ingredients brewing coups, resentment, youth involvement and more importantly – political decay.

Resentment directed toward institutions is amplified by a growing population. From Bangladesh to Tianmen, it’s clear that coups are always ignited by the embers of the young.

I’d like to reiterate the importance of political decay after understanding ideology. While ideology is one particular weapon to destabilize institutional integrity, there is also a possibility of decay from within. Corruption, and weakening of the rule of law ordained by other wings of the government all can be a subset of the will of that ideology, however, can act independently simply because of the failure to adapt over time. The decay of political institutions either over time or through an external force lowers the ability of the state to execute and provide basic functionalities, rendering a nation with what economists call – low state capacity. This low state capacity causes a chain of events resulting in bribery, nepotism, kickbacks and extortion which reinforces political decay automatically into the system.

With the lack of any incentive to preserve the status quo, we introduce yet another element into our discussion. The complacency of the defence complex. If I liken a coup to a dish, the first three can be the core ingredients anchoring the flavour to the dish, however, this one can be the seasoning. After the commencement of the coup, it’s clear that the people who are bound to suppress your attempt are the armed forces. However, it can backfire like in Turkiye or Myanmar. As we see what ensues in Bangladesh, the inability of the police forces to mobilize a response is bolstered primarily because of the mute support facilitated by the armed forces. What now we must be concerned about is that our neighbour should not become a repeat of Pakistan.

This now leads us to the final coup de grace. The handover. I deem this so primarily because of its importance. There is a unanimous agreement now that handover to the army implies the death of democracy. The seizure of power by an institution with the ability of violence is greater than that of a state itself implying the loss of people’s rights, case in point – Pakistan. The examples I provide can be innumerable from Burma to the Sahel, leading us back full circle to the start of the article. But what is the right method then? If the military seems to be an inappropriate alternative, who do we rely on then?

The seizure of power by an institution with the ability of violence is greater than that of a state itself implying the loss of people’s rights, case in point – Pakistan.

While I wish to provide a caveat to this question, it’s difficult to say. The presence of a strong opposition is the only appropriate answer one can come to terms with. A successful dictator is soundly aware of the problems an opposition might cause. To evade the combined threats posed by both the military institutions and the ideological harassment they might endure, the people need to have confidence in their decision to embrace the vibrant democracy they lay claim to via a coup and nominate an alternative. To rely on the justice system and maintain a renewed trust in the rebuilding institutions they seized is necessary. For finding an alternative, in particular, an opposition is pivotal in maintaining a healthy democracy. How Bangladesh now proceeds is a question we are left to wonder, however, the pages of history seem to indicate a dangerous path ahead.

(Divith Narendra is a student of data science, economics, and business with a passion for integrating data and statistics. He writes extensively on industry trends and geopolitics. His works were featured at the G20 and published by Cambridge Union Press. Views expressed are the author’s own)