|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

- The religious minorities, viz., Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Hindus, from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who arrived in India before December 31, 2014, because of persecution or were afraid of being persecuted on account of their faith, the CAA-2019 offers a route to Indian citizenship.

- The core objective is not to revoke citizenship but to grant it to specific religious minorities facing historical and ongoing persecution in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

- The CAA’s commitment to upholding principles of religious freedom and equality, within the secular fabric of India, underscores its humanitarian imperative to offer sanctuary to those who have endured persecution based on their religious identity.

(This explainer was first published by CIHS, New Delhi, to whom it belongs. Republished with permission.)

The Citizenship (Amendment) Rules, 2024 have been released by the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) today. These guidelines will specify the steps and prerequisites needed for qualified individuals to apply for Indian citizenship in accordance with the terms of the 2019 Citizenship (Amendment) Act (CAA-2019). The religious minorities, viz., Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis, and Hindus, from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who arrived in India before December 31, 2014, because of persecution or were afraid of being persecuted on account of their faith, the CAA-2019 offers a route to Indian citizenship. The documentation, forms, and other requirements that must be met by anyone wishing to apply for citizenship under this act will be detailed in the regulations notified by the MHA.

An important step towards operationalizing the CAA-2019 has been taken with the notification of the Citizenship (Amendment) Rules, 2024. This ensures efficiency and transparency in the process of granting citizenship to eligible applicants and clarifies the procedures. The CA Rules 2024 will provide clarification and direction to applicants and pertinent authorities engaged in the CAA-2019’s implementation.

Key Points on Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA):

• Implemented by the Indian Parliament on December 12, 2019.

• The core objective is not to revoke citizenship but to grant it to specific religious minorities facing historical and ongoing persecution in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

• The aim is to provide a legal pathway for citizenship to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian minorities from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan due to extreme religious persecution.

• Selective focus on these communities is rooted in historical and contemporary challenges faced by religious minorities.

• Any other faith, sex, creed or gender can apply for Indian citizenship through the normal immigration route which remains open for all.

• Reflects India’s commitment to religious freedom and equality, integral to its secular fabric.

• Not designed to alter or revoke the citizenship status of the existing Indian population.

• Legislative framework signifies support to those persecuted based on religious identity.

Key Provisions of CAA:

• Illegal migrants from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh entering before December 31, 2014, will not be treated as illegal migrants.

• Not applicable to illegal migrants from the Muslim community.

Page 5 of 13

• Not applicable to tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, or Tripura.

• Upon conferment of citizenship, pending legal proceedings related to illegal migration or citizenship stand abated.

• Reduces the period of residence for immigrants to five years instead of eleven.

Similar Amendments in the United States – Lautenberg Amendment:

• Introduced in 1990, it facilitated the resettlement of religiously persecuted minorities from the Soviet Union to the USA.

• Extended to minorities (Jews, Christians, and Baha’is) from Iran in 2004, known as the Specter Amendment.

• Similar to CAA, it specifically enlists religious communities from specific countries as ‘historically persecuted groups.’

• Excludes Muslims of Iran and the Soviet Union, identifying beneficiaries persecuted due to religion.

• Fast-tracks the time required for eligibility for citizenship, similar to CAA.

Contrasting Amendments in the United Kingdom – Nationality and Borders Act:

• Implemented in 2022, grants government authority to revoke citizenship without prior notice under Clause 9.

• Criticised for disproportionately affecting British Muslims, creating divisions based on ethnic and religious backgrounds.

• Security reasons cited and the case of Shamima Begum cited as an example.

• UK’s law amendment focuses on the revocation of citizenship.

• In contrast, India’s CAA aims to provide refuge to persecuted minorities without revoking anyone’s citizenship.

Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA)

Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of the Indian Parliament, implemented on December 12, 2019, has become a central topic in widespread discourse and misinformation within the media landscape, both in India and internationally. Proclaimed as the leading and most notable news outlets, have time after time contributed to misconstruing the essence of the act, fueling protests and generating unwarranted hysteria. Therefore, it is crucial to clarify that the CAA’s core objective is not to revoke citizenship from the current populace but to establish a systematic framework for granting citizenship to specific religious minorities facing persecution in select neighbouring nations, earlier a part of undivided Britain occupied India. As evidenced in its fine print, the fundamental essence of the CAA lies in its commitment to providing a legal pathway for citizenship acquisition to distinct religious communities—namely, Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian—who have sought refuge in India due to religious persecution in Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan.

The legislative initiative is explicit in its identification of these communities, reflecting an intention to expedite their assimilation into Indian society through the conferment of citizenship. The rationale behind the selective focus on these specific religious groups is deeply rooted in a nuanced understanding of the historical and contemporary challenges faced by religious minorities in the aforementioned countries, particularly those residing in Islamic-majority nations with historical ties to undivided India.

By addressing the humanitarian imperative of providing sanctuary, the CAA articulates a commitment to upholding the principles of religious freedom and equality, both integral to the secular fabric of India. The legislative framework signifies an affirmative step towards extending support to those who have experienced persecution solely on the basis of their religious identity.

Moreover, it is crucial to underscore that the CAA is not designed to alter the citizenship status of the existing Indian population, irrespective of their religious affiliations. Instead, the legislation delineates a specific course for offering citizenship to religious minorities seeking refuge in India due to persecution in neighbouring countries.

In conclusion, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) has undeniably stirred significant debate and misinformation, amplified by influential media outlets. However, amidst the clamour, it is imperative to recognise the genuine intent of the CAA – to provide a structured pathway for citizenship to persecuted religious minorities. Separating fact from fiction is essential in navigating the discourse surrounding the CAA, and a nuanced understanding of its objectives is crucial for a more informed and constructive dialogue on this complex and contentious issue.

Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019

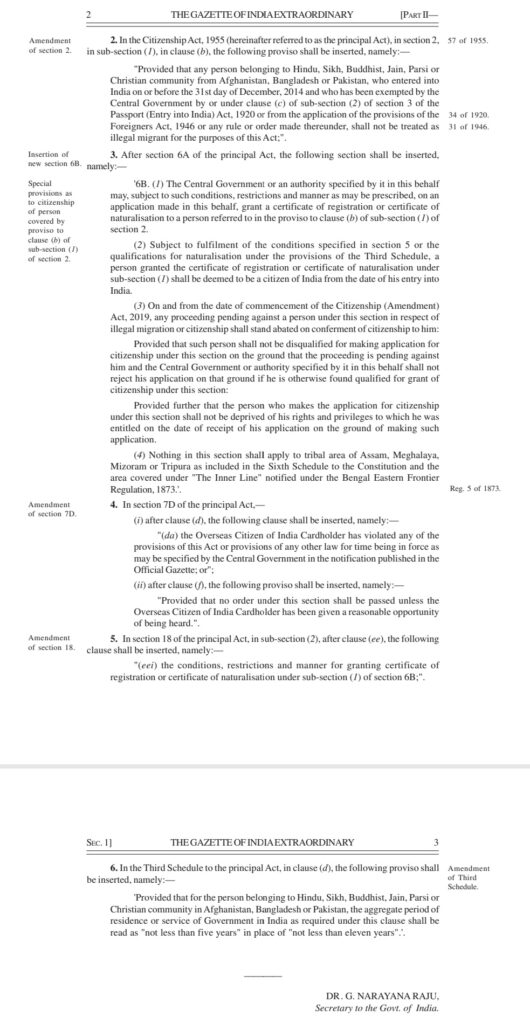

The Government of India in the year 2019 passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 with the objective of fast- tracking the process of granting Indian Citizenship to any person belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan, who entered into India on or before 31st day of December, 2014 and who has been exempted by the Central Government by or under clause (c) of sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920 or from the application of the provisions of the Foreigners Act, 1946 or any rule or order made thereunder, shall not be treated as illegal migrant for the purpose of this Act.

The main provisions under the CAA can be stated as under:

1. According to the Act, the illegal migrants from three countries (Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh) will no longer be treated as illegal migrants provided that they have entered into India on or before 31st December 2014.

2. The Act aims to provide citizen status to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi and Christian religious minorities from the above-mentioned countries due to religious persecution.

3. The act is not applicable to the Illegal migrants from the Muslim community.

4. The Act is not applicable to the tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram or Tripura as included in the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution and the area covered under “The Inner Line” notified under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873.

5. A person granted the certificate of registration or certificate of naturalisation shall be deemed to be a citizen of India from the date of his entry into India.

6. Upon conferment of citizenship, any legal proceeding pending against such person with respect to illegal migration or citizenship shall stand abated.

7. The Act has also reduced of period of residence for such immigrants to five years in place of eleven years.

Similar amendments; the example of the United States of America Lautenberg Amendment 1990

Ordinarily, refugees seeking entry or immigration status in a country are required to individually demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country. In the US, this requirement is found in Section 207 of the Immigration and Nationality Act3, the principal law governing immigration. The Lautenberg Amendment (Public Law 101-167) 1989, was introduced and spearheaded by one of the American senate’s most proactive and progressive

members, Frank Lautenberg, this program initially facilitated resettlement of religiously persecuted minorities from Soviet Union (Jews, Evangelical Christians, Ukrainian Catholics, and members of Ukraine Orthodox Church) to USA. A similar law was passed in 2004, known popularly as the Specter Amendment, extends this benefit to minorities (Jews, Christians and Baha’is) from Iran. These are jointly called as the Lautenberg-Specter Amendment4. This law, therefore, specifically enlists religious communities in former Soviet Union and religious minorities in the Islamic Republic of Iran in order to confer a benefit on them to the exclusion of all other refugees, the benefit being that they don’t need to individually demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution.

Sub-section (d), in fact, permits applicants belonging to these categories to reapply if their refugee applications were denied due to the fact that they could not individually demonstrate a well-founded fear of persecution. The Lautenberg- Spector Amendment needs to be renewed every year to remain a law, something which all the Governments of United States have done religiously notwithstanding the party or President in office.

United States program that started in 1990s had a lot of similarities to CAA under an amendment called Lautenberg Amendment. Named after Frank Lautenberg (a NJ Democrat), this program initially facilitated resettlement of religiously persecuted minorities from Soviet Union (Jews, Evangelical Christians, Ukrainian Catholics, and members of Ukraine Orthodox Church) to USA. It was later extended to other countries such as Iran by Specter Amendment for the benefit of minority communities ( Jews, Christians and Baha’is. India’s CAA can be concluded as a policy that is very similar to Section 207 of the Immigration and Nationality Act, pursuant to which refugees fleeing any country individually and demonstrating a well-founded fear of persecution on any ground (race, religion, sex, nationality, ethnic identity, membership of a particular social group or political opinion) are provided long-term visas. This benefit is accorded through the Standard Operating Protocol (SOP) dated 29 December 2011, which permitted such refugees to take up employment in private sectors and undertake studies in academic institutions. And further after proving eleven years of residency in India, they become eligible to apply for Indian citizenship pursuant to the Indian Citizenship Act, 1955. Furthermore, CAA’s only effect is to enlist specific categories of people (Hindu, Parsi, Sikhs, Buddhist, Jains & Christians ) from specific countries (three neighbouring nations of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh) as ‘historically persecuted groups ’which was similar to the Lautenberg Amendment obviating the need for them to meet the individual demonstration requirement.

In addition to this, the CAA fast-tracks the amount of time these specific categories need to physically be in India and in order to be eligible to apply for Indian citizenship i.e as per CAA, the provision under the previous Act, Citizenship Act,1995 it was a pre-requisite that a person is physically residing in India for eleven years which now under CAA has been made to five years. Further it can also be stated that the Lautenberg Amendment specifically excluded Muslims of Iran and Soviet Union and hence, it identified beneficiaries persecuted due to religion in the same manner just like CAA.

Contrasting amendments; the example of the United Kingdom Nationality and Borders Act 2022

In 2022, the United Kingdom implemented a new citizenship law under the Nationality and Borders Act, known for its controversial Clause 9, granting the government the authority to revoke citizenship without prior notice.5 A recent report by the Institute of Race Relations

(IRR) has raised concerns, asserting that this law has led to the creation of second-class citizens, particularly impacting British Muslims of South Asian heritage. This article aims to explore the discriminatory aspects of the UK’s citizenship laws in contrast to India’s Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which has different objectives and consequences.

The focal point of criticism in the UK’s Nationality and Borders Act is Clause 9, which empowers the government to strip British citizens of their citizenship while abroad under certain conditions. The IRR’s report argues that this disproportionately affects British Muslims, with a particular emphasis on those of South Asian and Middle Eastern heritage. The case of Shamima Begum, who lost her citizenship after being involved with the Islamic State at a young age, is cited as an example. The IRR contends that the changes in citizenship law, including the introduction of Clause 9, target British Muslims and create divisions among citizens based on ethnic and religious backgrounds. In response to the report, a Home Office spokesperson defended the law, emphasizing its application to a limited number of individuals who pose serious threats to national security. The government maintains that the power to revoke citizenship is exercised judiciously against individuals involved in fraud, terrorism, extremism, and serious organised crime. However, critics argue that the removal of the notification requirement impedes individuals’ ability to challenge decisions effectively. The IRR report highlights the ambiguous criteria for citizenship deprivation, raising concerns about arbitrary and discriminatory decision-making. The spokesperson’s assertion that the law affects only a handful of people is met with skepticism, as the report suggests a broader impact on minority ethnic communities, specifically British Muslims.6 In contrast to the UK’s approach, India’s Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) introduced in 2019 has a different objective. The CAA does not involve the revocation of citizenship but focuses on providing citizenship to individuals who are victims of historic and ongoing persecution in Muslim majority states that were originally part of India. While the CAA has faced its share of criticism, particularly regarding concerns about religious discrimination as a result of misrepresentation and false narrations, it fundamentally differs from the UK’s law in its purpose. The CAA aims to protect persecuted minorities, particularly non-Muslims, in neighbouring countries.

The introduction of Clause 9 in the UK’s Nationality and Borders Act has sparked debates on its potential discriminatory effects, especially on British Muslims. The IRR report underscores concerns about the creation of a second-class citizenship category for minority ethnic Britons. It is crucial to examine such legislation in a global context, acknowledging the contrasting approach of India’s CAA, which, despite its own controversies, centers on providing refuge rather than revoking citizenship.

Concluding Observations

In conclusion, the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India, enacted in 2019, has been a subject of extensive debate and scrutiny both nationally and internationally. Despite the widespread misinformation and sensationalism surrounding the act, a nuanced examination of its key provisions and objectives reveals a legislative framework primarily focused on providing a structured pathway for citizenship to religious minorities facing persecution in specific neighbouring nations. The CAA’s commitment to upholding principles of religious freedom and equality, within the secular fabric of India, underscores its humanitarian imperative to offer sanctuary to those who have endured persecution based on their religious identity. Drawing parallels with similar amendments in the United States, such as the Lautenberg Amendment, highlights commonalities in the approach to addressing the plight of persecuted minorities. However, the distinct nuances of the CAA, particularly its emphasis on historical ties and regional challenges, underscore its unique context within India’s socio-political landscape. On the other hand, the contrasting example of the United Kingdom’s Nationality and Borders Act, with its controversial Clause 9, showcases a different approach where citizenship can be revoked without prior notice, sparking concerns about potential discrimination against specific ethnic and religious groups. The debates surrounding the UK’s law underscore the importance of examining citizenship legislation in a global context and emphasize the need for transparency, accountability, and protection of individual rights. In navigating the discourse surrounding the CAA and similar amendments, it is imperative to separate fact from fiction, recognising the genuine intent of these legislative measures.

References

Media

- https://vskbharat.com/caa-protest-10-fake-news-about-the-citizenship-act-spread-by-anti-national-media-and-jihadi-journos/?lang=en

- https://twitter.com/DDNewslive/status/1767182626060677402

Acts

- India, The Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019,s 2 (1) (b)

- US, Immigration and Nationality Act 1952, s 207

- https://www.parliament.uk/business/news/2021/december-2021/lords-debates-nationality-and-borders-bill/

Think Tanks

- https://irr.org.uk/article/citizenship-from-right-to-privilege/#:~:text=

- Roll Call. 2014. Honouring Frank Lautenberg’s Legacy for Refugees | Commentary – Roll Call. [online] Available at: <https://www.rollcall.com/2014/06/02/honoring-frank-lautenbergs-legacy-for-refugees-commentary/