|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

- Auroras occur when charged particles emitted by the Sun, known as the solar wind, interact with Earth’s magnetosphere.

- The Northern Lights are not just a spectacular natural wonder but also a fascinating intersection of solar physics and atmospheric science.

- For the first time, the Indian Astronomical Observatory captured this phenomenon above Mount Saraswati in Ladakh’s Hanle region.

The Northern Lights, or Aurora Borealis, are one of nature’s most mesmerising phenomena, captivating skywatchers across the globe.

An aurora is a natural display of dynamic patterns of brilliant lights in Earth’s sky. Auroral activities occur due to the interaction between the Earth’s magnetosphere and the incoming solar wind that carries charged particles and magnetic fields. They predominantly are witnessed in high latitudes near the Arctic, and Scandinavian countries. These ethereal lights occasionally make their way to lower latitudes, including parts of the UK and the USA, during periods of intense solar activity. Understanding the mechanics behind this dazzling display involves delving into solar physics and geomagnetic storms.

The Science Behind the Aurora

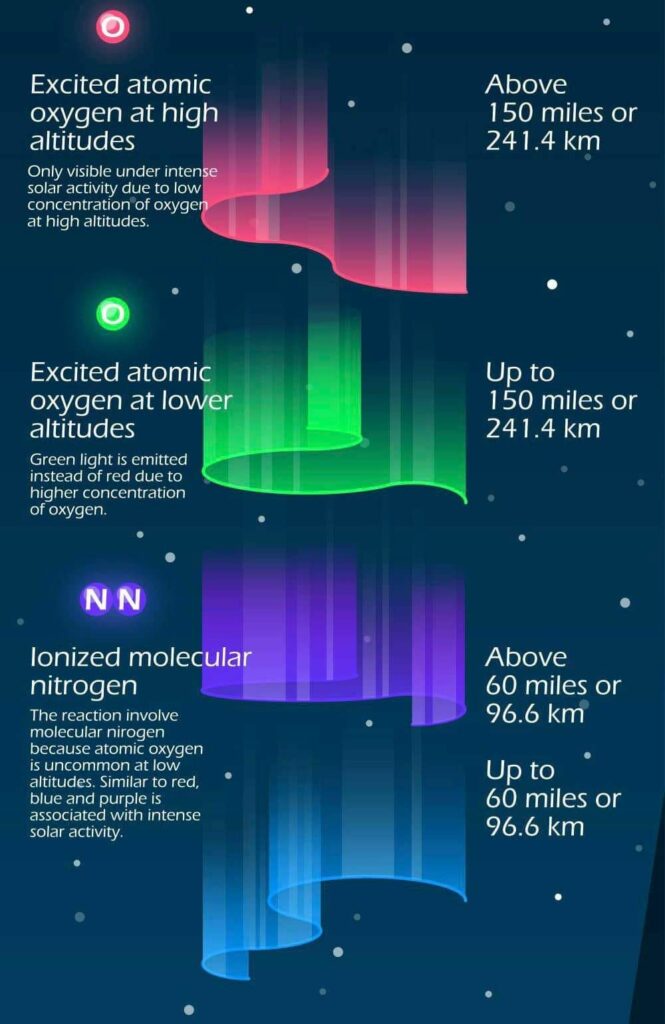

Auroras occur when charged particles emitted by the Sun, known as the solar wind, interact with Earth’s magnetosphere. This interaction is particularly intense when the Sun releases a large number of particles during events like solar flares or coronal mass ejections (CMEs). As these particles travel along the Earth’s magnetic field lines towards the poles, they collide with gases in the atmosphere, such as oxygen and nitrogen. These collisions emit light, creating the shimmering curtains of green, pink, red, and purple that characterise auroras.

Geomagnetic Storms and the G-Scale

Geomagnetic storms are disturbances in Earth’s magnetosphere caused by solar activity. These storms are classified using the G-scale, which ranges from G1 (minor) to G5 (extreme):

- G1 (Minor): Can cause weak power grid fluctuations and minor impacts on satellite operations.

- G2 (Moderate): This may affect high-latitude power systems and have a more noticeable impact on satellite and radio operations.

- G3 (Strong): This can lead to voltage corrections in power systems and more significant impacts on satellite operations.

- G4 (Severe): Causes widespread voltage control problems and may impact navigation systems.

- G5 (Extreme): This leads to major power grid failures, and widespread satellite issues, and can result in auroras being visible much farther from the poles.

Recent Powerful Sightings

In recent years, several notable geomagnetic storms have expanded the reach of the Northern Lights:

- May 2024: This is the biggest Geomagnetic storm since 2003 in terms of its strength as the flaring region on the Sun was as big as the historically important Carrington event that took place in 1859. Multiple X-class flares and CMEs have hit the earth in the past 1-2 days. (May 10-12 2024)

- March 2023: A G4 geomagnetic storm made the Northern Lights visible as far south as Arizona and New Mexico in the USA, and southern parts of the UK.

- October 2022: A G3 storm illuminated skies across Canada and the northern USA, with some sightings reported as far south as Colorado.

- August 2021: A G2 storm allowed sightings in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the northern USA.

These events highlight the variability and sometimes surprising extent of auroral displays during periods of heightened solar activity.

For the first time, the Indian Astronomical Observatory captured this phenomenon above Mount Saraswati in Ladakh’s Hanle region. The stunning red auroral arc was first observed around 1 am on May 11 and is forecasted to continue over the weekend due to ongoing interactions between coronal mass ejections and Earth’s outer atmosphere.

Ladakh, typically outside the common range for such displays, witnessed this due to a severe G4 geomagnetic storm. This classification comes from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Space Weather Prediction Center, highlighting the intensity of the event.

Notably, a similar phenomenon occurred on April 22-23, 2023, following a coronal mass ejection on April 21. This event also triggered a G4 geomagnetic storm, showcasing the dynamic nature of space weather impacts on our planet.

The recent geomagnetic activities are part of a larger pattern of solar activity, which experts suggest could become more frequent as we approach the solar maximum. The interplay of these solar storms with Earth’s magnetic field often results in such captivating displays, offering both scientific intrigue and visual splendour.

Future Predictions

Solar activity follows an approximately 11-year cycle, with periods of maximum and minimum activity. We are currently approaching a solar maximum, expected around 2025, which should increase the frequency and intensity of geomagnetic storms. During this period, more frequent G3 and above storms are anticipated, potentially allowing for more widespread aurora sightings:

- 2024-2025: Predicted to have multiple G4 and possibly G5 storms, offering prime opportunities for aurora viewing in regions far from the poles, including the northern USA and UK.

- 2026-2027: As the solar cycle progresses towards its declining phase, G3 storms will still be likely, though less frequent than during the solar maximum.

The Northern Lights are not just a spectacular natural wonder but also a fascinating intersection of solar physics and atmospheric science. As we move towards the next solar maximum, skywatchers in lower latitudes may have more opportunities to witness this breathtaking phenomenon. Whether you are a seasoned aurora chaser or a curious observer, the coming years promise a front-row seat to one of nature’s most captivating displays.

Prepare your cameras and keep an eye on space weather forecasts; the dance of the Northern Lights is a show you won’t want to miss!

(The author is a student of law and a communication professional. Her interests lie in governance, public policy & law and is part of the foundational batch of the Indian School of Public Policy, New Delhi)