- Control of grain exports has shifted from merely an economic advantage to a potent geopolitical weapon.

- Russia has become a supplier of cheaper wheat to African countries, particularly those that abstained from voting on UN resolutions condemning the invasion of Ukraine, creating a quid pro quo where food security is turned into diplomatic support.

- India frames its wheat exports as an act of solidarity with the Global South—and yet is not impervious to the same geopolitical realities informing its decisions.

- In an age of climate uncertainty and resource constriction, food security is not just about feeding people—it’s about constructing the world order.

Introduction: When Wheat Becomes Weaponry

In the shadowy realm of 21st-century geopolitics, an entirely new currency is now in contention alongside oil, rare earth specialities and military power: wheat. Climate change continues to threaten the security of agriculture, and the world’s population extends beyond eight billion people. Therefore, control of grain exports has shifted from merely an economic advantage to a potent geopolitical weapon. At the centre of the “grain war” are two unlikely competitors, Russia and India, each engaged in the currency of wheat diplomacy to forge new international ties in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.

The invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 highlighted this fact. Russia’s blockade of the Ukrainian ports impacted not only the supply chain but also underscored the fragility of global food security and the capacity of wheat-dependent nations to be held hostage. Now India has emerged, not just as an alternative supplier, but as a lever—a democratic nation engaging in food diplomacy as a hedge against Russian and Chinese influence in the Global South.

The Numbers Tell the Story: Production Powerhouses

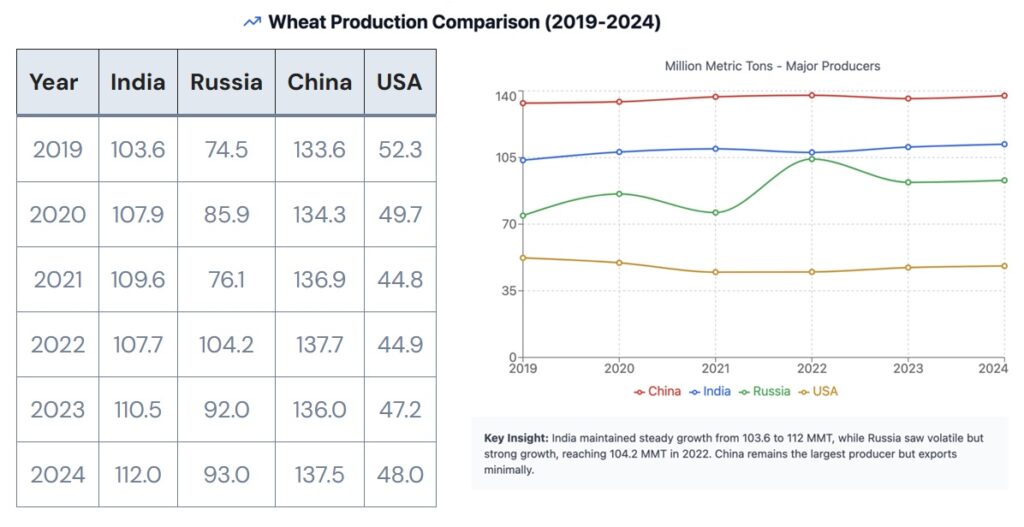

In the past decade, India and Russia have fundamentally changed their roles in the international wheat markets. Production of wheat in India has slowly risen from 103.6 million metric tons in 2019 to nearly 112 million metric tons in 2024, putting it in the second spot globally, just behind China. In contrast, Russia experienced explosive growth in production to a level of 104.2 million metric tons in 2022, huge growth attributable to excellent weather and increased plantings in its southern regions.

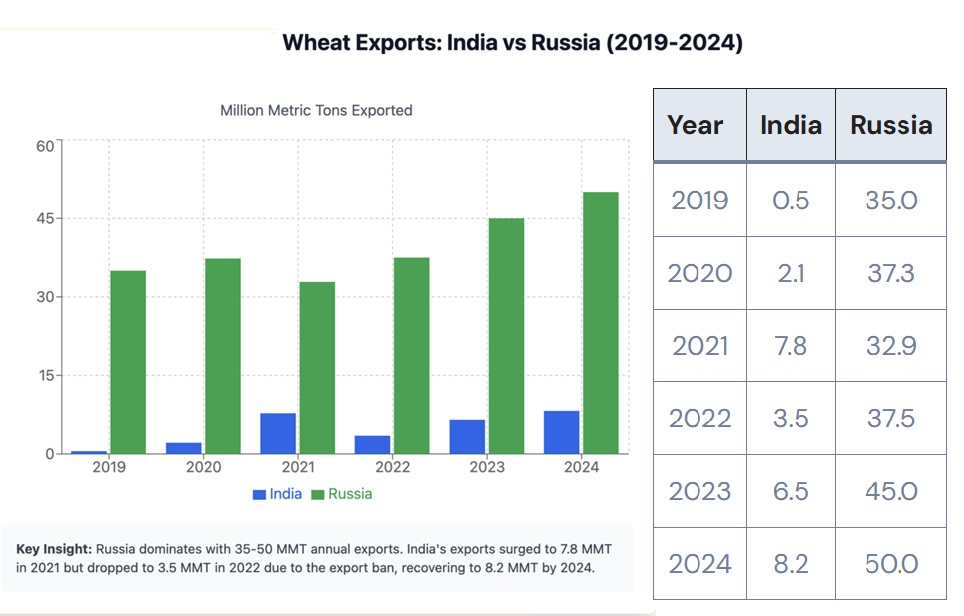

Production is only one part of the story; however, export capacity is the real geopolitical power. Since 2020, Russia has regularly exported between 35-50 million metric tons each year to be the largest exporter of wheat in the world. India’s export capacity has not been straightforward or predictable, but it has been crafty. From a low of 0.5 million metric tons in 2019, Indian wheat exports shot up to 7.8 million metric tons in 2021 when there was a surge in wheat demand globally. A heat wave in 2022 forced India to put a ban on wheat exports, sending the price of wheat up by 6% overnight. The rapidity with which food security can become a geopolitical issue is stark.

Strategic Export Destinations: The Battle for Influence

The true geopolitical contest emerges into view if one considers where these wheat exports end up. Russia has purposely cultivated dependencies in Africa and the Middle East, with Egypt importing nearly 80% of its wheat from Russian wheat, Turkey about 70%, and Nigeria disproportionately dependent on Black Sea grain. This is not by accident—this is statecraft. Russia has become a supplier of cheaper wheat to African countries, particularly those that abstained from voting on UN resolutions condemning the invasion of Ukraine, creating a quid pro quo where food security is turned into diplomatic support.

India’s export strategy indicates a different hierarchy of priorities. Russia holds influence over Africa and the Middle East, while India has prioritised South Asia—particularly Bangladesh and Sri Lanka—and selectively targets African countries where it sees resistance to the Chinese Belt and Road initiative. India has shipped wheat to Afghanistan during times of humanitarian disaster, to Yemen amid continuous conflict, and to other countries across Africa, consistent with its stated “Vishwaguru” (world teacher) objective. While Russia is transactional, India frames its wheat exports as an act of solidarity with the Global South—and yet is not impervious to the same geopolitical realities informing its decisions.

The 2022 Watershed: India’s Export Ban and Global Shockwaves

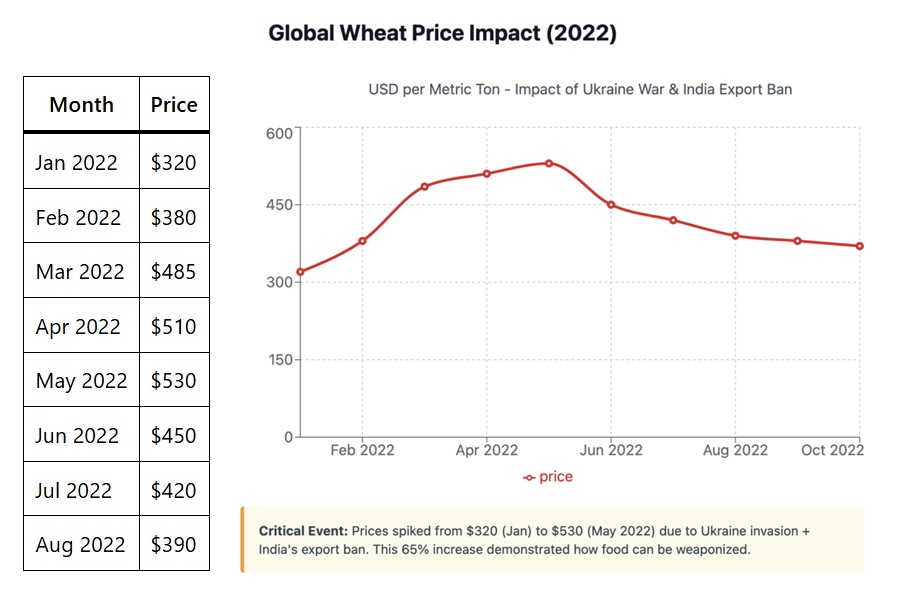

May 2022 was the inflexion point in grain geopolitics. As record-high heatwaves baked India’s wheat-growing areas, the government abruptly halted wheat exports to safeguard national food security. Wheat prices had already been elevated internationally because of Ukraine disruptions, but escalated immediately from around 450 USD per metric ton to 530 USD in just weeks. The signal was unmistakable: India, like Russia, could leverage food exports as geopolitical currency—and chose internal stability over international commitments.

The move was internationally condemned. The World Trade Organization regretted the move; G7 nations protested; and countries like Egypt and Bangladesh looked for alternative sources. But India’s calculation was straightforward: with 1.4 billion people and colonial famine memories, local food security is paramount over global market commitment. The ban was later selectively lifted for some countries by way of government-to-government deals, turning wheat from a commodity into a tool of foreign policy.

The signal was unmistakable: India, like Russia, could leverage food exports as geopolitical currency—and chose internal stability over international commitments.

The Russia Factor: Fertilisers, Energy, and Complex Dependencies

India’s wheat strategy is linked to a complicated web of dependencies with Russia itself. While it is also attempting to sell itself as an alternative to Russian grain, India greatly relies on Russian fertilisers and imports about 2-3 million metric tons of urea and fertilisers annually at discounted prices. Coupled with this, India’s increase in oil imports from Russia since the invasion of Ukraine, which now exceeds 2 million barrels per day in 2024, adds another layer of interdependency.

This creates a fascinating geopolitical contradiction—India is competing with Russia for wheat export markets in parts of Africa and West Asia, but depends on Russian inputs for its own farming production. India’s ability to balance both this and produce a favourable outcome for its Western “partners” looking for alternatives to Russian grain, as it works toward strategic autonomy with Russia, showcases the multipolar complexity of current geopolitics.

Climate Change: The Wildcard Reshaping the Board

Both India and Russia are experiencing a life-threatening threat due to climate change that will change how grain is geopolitically positioned. India’s growing wheat belt is increasingly vulnerable to extreme heat episodes, and a heat wave that occurred in Punjab and Haryana in 2022 resulted in a yield decrease of 5%-10% in those states. Climate models project that rising temperatures will result in a yield decrease of 15%-30% in wheat across South Asia by 2050 and shift India from a wheat exporter back to a wheat importer.

Russia is in the opposite situation. Warmer temperatures have lengthened growing seasons in Siberia, further opening up vast amounts of agricultural land. Models predict that Russian wheat production could increase 20%-40% by 2040, confirming Russia’s position and retaining its status as the world’s largest wheat exporter. The divergence in climate will alter the wheat rivalry between India and Russia, with Russia strengthening its position while India struggles to remain self-sufficient.

The China Variable: The Silent Third Player

While India and Russia compete for export markets, China is quietly taking its place as the third player. China is the world’s largest wheat producer (about 137 million metric tons) and largest wheat importer (approximately 8-10 million metric tons per year), making it an important factor in wheat prices globally. China has abundant grain reserves—estimated at 50 – 60% of global stock—providing some insulation against food security and a measure of leverage in the market.

China has invested billions in agricultural infrastructure through its Belt and Road Initiative, specifically in Central Asia and Africa, and has also helped enable alternative agricultural supply chains out of Africa that are not within the Indian or Russian sphere of influence. As a very specific example of agricultural infrastructure plans, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor plan includes agricultural development. Beyond Central Asia, China is investing in agricultural development in Ethiopia and Kenya to fundamentally change Africa’s dependence on imports. The Belt and Road Initiative, in particular, is a long-term strategy that may be much more sustainable than short-term agricultural export diplomacy.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Grain Geopolitics

The disputes surrounding grain between India and Russia signify a clash greater than grain disputes between the two countries. It represents a change in how countries understand food security as related to national security, and several important trends in this system will emerge in the next seven years, running through to 2030. Climate volatility will increasingly govern the ability to supply commodities and can create sudden supply shocks and crises of diplomacy. There are also opportunities represented by technology improvements to drought-resistant crops, and precision agriculture may develop to the point where countries like India could grow food without pressures from climate change. Food weapons themselves could catalyse global efforts by countries to create strategic grain reserves or other agreements to ensure supply.

In the case of India, much depends on 1) being able to guarantee domestic food security against pressures from climate change, 2) being a reliable, democratic substitute for the exports of Russia, and 3) balancing serving the circumstances of its neighbours with retaining sovereignty in an autonomous space, while being engaged with Moscow through diplomatic efforts. This entails significant investments in climate resilient agriculture, irrigation system development, and a level of diplomatic skill in navigating competing webs of engagement with the West, Russia and with Global South.

The divergence in climate will alter the wheat rivalry between India and Russia, with Russia strengthening its position while India struggles to remain self-sufficient.

Conclusion: Wheat as the Currency of Power

The India-Russia wheat competition highlights how geopolitics in the 21st century is increasingly defined by the control of resources, not military power. With populations expanding, climates changing, and nations looking for diversification from China-based supply chains, agricultural goods—especially commodity grains—have themselves become tools of statecraft as valuable as sanctions or security assurances.

India’s ascension to wheat power is an opportunity and vulnerability. It provides a democratic counterpoint to Russian and Chinese dominance of the Global South, but is circumscribed by internal food security needs and climatic vulnerability. Russia, in contrast, seems to be well-positioned to reinforce its status as climate change fortuitously increases its agricultural capacity. The countries that navigate this emerging grain geopolitics most effectively will be the ones that see the central truth: in an age of climate uncertainty and resource constriction, food security is not just about feeding people—it’s about constructing the world order.

The wars of grains have just started, and the result will decide which countries possess leverage in the multipolar world of the mid-21st century. The way forward for India is not only growing wheat, but also deploying it strategically as an instrument of influence while making sure domestic requirements never again generate the weaknesses against which colonialism exploited it. In this game of chess conducted with wheat instead of swords, every harvest is a geopolitical occurrence, and every export choice a declaration of national strength.

Key Statistics Summary

- India’s 2024 Production: 112 Million Metric Tons

- Russia’s Annual Exports: 50 Million Metric Tons

- Price Spike in 2022: 65%

- Egypt’s Dependence on Russia: 80%

- Bangladesh’s Wheat from India: 65%

Primary Data Sources:

- Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) | Website: https://www.fao.org/faostat/ | Data Used: Global wheat production statistics (2019-2024), export volumes, and country-specific production data. Specific Dataset: FAOSTAT – Crops and livestock products

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) | Website: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0430000 | Data Used: Wheat production forecasts, export data, and global supply and demand estimates. Specific Reports: World Agricultural Production (WAP) reports, Production, Supply and Distribution (PSD) database

- India Ministry of Agriculture & Farmers Welfare | Website: https://agricoop.nic.in/ | Data Used: India’s wheat production statistics, state-wise production, and export policies. Specific Reports: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance (annual reports)

- UN COMTRADE (United Nations International Trade Statistics) | Website: https://comtradeplus.un.org/ | Data Used: Bilateral trade flows, wheat export destinations by country

- World Bank – Commodity Price Data | Website:https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/commodity-markets | Data Used: Global wheat prices (2022 spike analysis) | Dataset: Pink Sheet – Monthly commodity prices

- International Grains Council (IGC) | Website: https://www.igc.int/ | Data Used: Global grain market analysis, export forecasts

Geopolitical Analysis Sources:

- Chatham House (Royal Institute of International Affairs) – Research papers on food security and geopolitics, Analysis of Russia’s weaponisation of grain exports

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace – Relevant Article: “Russia’s Food Weapon”, Analysis of grain diplomacy in Africa and the Middle East

- Observer Research Foundation (ORF) – India | Website: https://www.orfonline.org/ | India-centric geopolitical analysis on wheat exports and strategic autonomy

- Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) – Articles on the global food security crisis post-Ukraine invasion

Specific Events & Reports Referenced:

- India’s 2022 Wheat Export Ban | Source: Government of India press releases (May 13, 2022) | Policy Document: Notification No. 02/2015-2020 (Directorate General of Foreign Trade).

- WTO Concerns on Export Restrictions | Source: World Trade Organization statements (June 2022). Reports on agricultural export restrictions

- Climate Impact Studies | Source: IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) reports, Studies on wheat yield projections under climate change scenarios

- Regional assessments for South Asia and Russia | Egypt-Russia Wheat Dependency | Source: Egyptian Ministry of Supply and Internal Trade data. Reports from the Arab Organization for Agricultural Development (AOAD)

News & Current Affairs Sources:

- Reuters & Bloomberg – Real-time wheat price tracking, News on India’s export policies and Russia’s grain deals

- The Hindu, Indian Express, Economic Times – India-specific agricultural policy coverage, Domestic wheat production and policy analysis

- Financial Times & Wall Street Journal – Geopolitical analysis of food security, Russia-Africa grain diplomacy coverage,

Academic & Think Tank Papers:

- Journal of International Affairs | Research on food security as a geopolitical weapon

- Asian Development Bank (ADB) | South Asian food security reports, Climate vulnerability assessments

- International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) | Website: https://www.ifpri.org/. Research on food price volatility and trade policies

Key Statistical Figures – Source Breakdown:

| Data Point | Primary Source |

| India Production (103.6-112 MMT) | FAO FAOSTAT + India Ministry of Agriculture |

| Russia Production (74.5-104.2 MMT) | USDA PSD Database + FAO |

| Export Volumes | UN COMTRADE + USDA FAS |

| Price Data ($320-$530) | World Bank Pink Sheet |

| Egypt’s 80% dependency | UN COMTRADE bilateral trade data |

| Regional export shares | UN COMTRADE + National customs data |

Divyanka Tandon holds an M.Tech in Data Analytics from BITS Pilani. With a strong foundation in technology and data interpretation, her work focuses on geopolitical risk analysis and writing articles that make sense of global and national data, trends, and their underlying causes. Views expressed are the author’s own.