- Before 2014, India broadly followed the international economic reform template of rapid liberalisation and shrinking the role of the state.

- India’s macroeconomic conditions have been relatively balanced in recent quarters, which include robust growth accompanied by exceptionally low inflation.

- India’s current phase illustrates that high growth and stability can often be pursued simultaneously.

- This is enabled through aligned structural reforms, macroeconomic discipline, and enhanced institutional capacity.

India mostly followed the international economic guidelines before 2014. The plan was to swiftly liberalise, shrink the state, and trust that growth would eventually trickle down. This approach, which was popular in the 1990s and early 2000s, was incompatible with India’s actual conditions, which included a substantial informal economy, a feeble state, and stark structural divisions.

These flaws weren’t coincidental. After 1991, liberalisation increased overall growth, but the informal economy remained largely unaffected as the benefits were concentrated in the formal and urban sectors. Uneven growth, growing inequality, high unemployment, and susceptibility to outside shocks were the outcomes of this.

These results were consistent with the cautions of economists such as Dani Rodrik, who contended that in the absence of robust institutions, markets operate inefficiently. Liberalisation can increase output but fail to produce widespread, sustainable prosperity in the absence of capable states, strong regulation, and mechanisms to handle distributional conflicts (Rodrik, 1999, 2000, 2002).[1]

This historical background emphasises how important India’s recent performance is. India’s macroeconomic conditions have been relatively balanced in recent quarters, with robust growth accompanied by exceptionally low inflation, resilient investment and exports, and stability in the financial sector.

This combination stands out amid challenges in many emerging markets and ongoing inflation in advanced economies. Drawing on ideas from academics like Joseph Stiglitz (1998; 2002) and Dani Rodrik, who support strategic state involvement in addition to market mechanisms, it represents a purposeful shift toward a pragmatic framework.[2] The markets continue to be the main distributors of resources. The state has taken on an enabling role as a facilitator through sector-specific incentives, a coordinator via public investment to crowd in private capital, and a provider of social protection.

Macroeconomic management has placed a strong emphasis on prudence combined with flexibility, including trade openness that is strategic rather than unconditional and fiscal consolidation combined with targeted support. By combining supply-side reforms with distributional strategies like direct benefit transfers, digital public infrastructure has improved efficiency, formalisation, and inclusivity.

GDP: Stable and Strong Growth

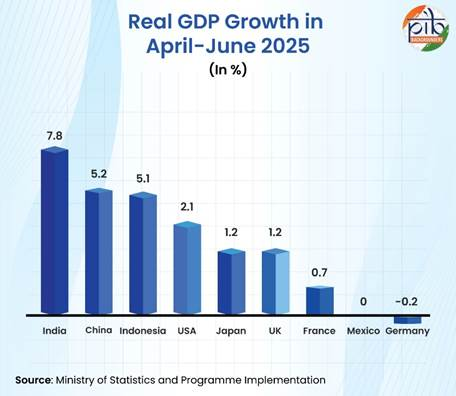

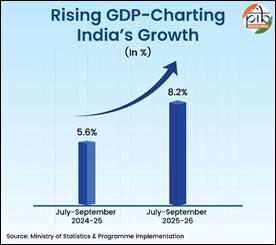

This reorientation is evident in India’s growth trajectory. In Q2 FY 2025-26 (July-September 2025), real GDP grew by 8.2%, the most in six quarters. This supported full-year projections above 7% and kept India as the fastest-growing major economy.[3]

Resurgence of Manufacturing and Strategic Trade

With India currently having the fifth-largest manufacturing economy in the world, manufacturing has been a major area of advancement. In August 2025, the Manufacturing PMI hit an 18-year high of 59.3, indicating a significant increase in orders, output, and employment. Additionally, the Services PMI has remained in expansionary territory, indicating the strength of the economy as a whole.[4]

Infrastructure upgrades, GST-driven formalisation, and production-linked incentives seem to be helping to address the “missing middle,” or the lack of mid-sized businesses. India is repositioning itself as a production hub in industries like electronics, automobiles, renewable energy, and defence, thanks to trade agreements with nations like the UK, Oman, and New Zealand, as well as initiatives to integrate into global value chains.

Effective Management of Inflation

The control of inflation has been remarkably effective. Although headline CPI inflation rose from 0.25% in October to 0.71% in November 2025, it was still well below the Reserve Bank of India’s tolerance range. [5]

Given that advancements in formalisation, logistics, digital payments, and supply-chain management have lessened previous bottlenecks, this calls into question the conventional wisdom that high growth inevitably drives inflation.

Exports, Investment, and Self-Belief

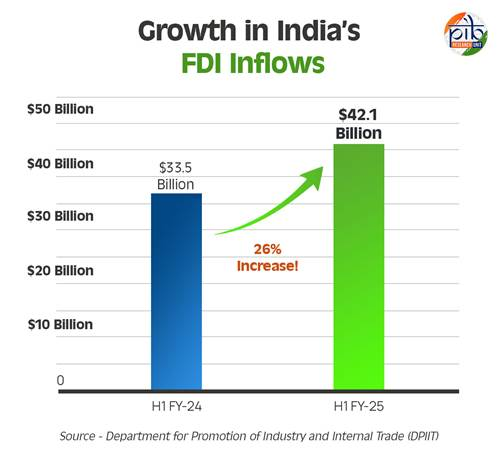

In FY 2024–2025, foreign direct investment inflows reached a record $81 billion, up 14% year over year, with a focus on manufacturing and services. Major companies’ commitments demonstrate their long-term faith in India’s future. The total amount of foreign direct investment (FDI) from 2014 to 2025 is close to $749 billion, with sources spreading across more nations. Exports of goods and services have been steadily increasing, and forecasts indicate that this trend will continue.[6]

Stability in the Face of Global Challenges

Recent years have avoided emergency measures, balance-of-payments pressures, or sharp tightening, in contrast to previous periods characterised by crisis management or abrupt policy shifts. Without speculative excesses, demand has increased steadily thanks to policies like the rationalisation of the GST rates.

Institutional Strength and Policy Credibility

Earlier periods sometimes featured tighter monetary policy to safeguard external ratings, potentially constraining growth, or expansionary measures contributing to inflationary or fiscal pressures. Policy uncertainty in the early 2010s was amplified by institutional coordination challenges between the Centre and States, as well as regulatory disputes.

In recent years, policy has emphasised rule-based approaches, including consistent inflation targeting, predictable investment rules, and systematic tax reforms. Credibility has been supported by institutional continuity, demonstrated outcomes, and digital infrastructure enabling efficient public delivery.

Navigating Inevitable Tradeoffs

India’s post-2014 economic policy framework has improved the management of classic macroeconomic trade-offs—such as growth versus inflation and external openness versus stabilityrelative to the pre-2014 period, particularly in terms of resilience to shocks.

During 2004-2014, average annual GDP growth was around 7%, but episodes of high growth often coincided with elevated inflation (averaging over 8%), widening current account deficits (peaking at 4.8% of GDP in 2012-13), and fiscal pressures, contributing to vulnerabilities during global events like the 2013 taper tantrum.

In the subsequent period (2014-2025), overall average growth has been moderated (~6%, affected by the COVID-19 shock), though recent years have seen a strong rebound with rates above 7%. Inflation has averaged around 5%, current account deficits have typically remained under 1-2% of GDP, and external resilience has improved.

This improved equilibrium, avoiding the boom-bust cycles seen earlier, stands out against peers like Brazil and Turkey, which grappled with higher inflation and recurrent crises, or even China and Indonesia, where growth moderation has been more pronounced amid global headwinds.

These transitions were accompanied by certain adjustment challenges, for example, for the informal sector, such as the reported employment shifts in unincorporated enterprises, even as aggregate growth accelerates. Manufacturing’s share in GDP has hovered around 15-17%, but yielded somewhat slower gains in labour-absorbing opportunities and the development of mid-sized firms.

Elevated public capital expenditure has effectively crowded in private investment and raised potential output, even as fiscal consolidation keeps deficits in the 4.4-4.8% range. Recent trade agreements have broadened market access and bolstered export resilience amid global pressures, promising longer-term advantages for agriculture and MSMEs, though they also entail greater competitive exposure for smaller producers in labour-intensive segments like textiles and dairy.

Similarly, digital public infrastructure continues to prompt legitimate discussions around data privacy and procedural safeguards under frameworks like Aadhaar and the Digital Personal Data Protection regime.

India’s current phase illustrates that, through aligned structural reforms, macroeconomic discipline, and enhanced institutional capacity, high growth and stability can often be pursued simultaneously, even if some classic trade-offs persist. This pragmatic approach offers valuable insights for other emerging economies navigating similar challenges. This quiet triumph marks a distinctive, pragmatic Indian model.

References:

- [1] https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w7540/w7540.pdf

- [2] https://archive.globalpolicy.org/socecon/bwi-wto/stig.htm

- [3] https://www.thehindu.com/business/Economy/indian-economy-grows-82-in-q2-2025-26/article70334383.ece

- [4] https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/manufacturing-by-country

- [5] https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2209412®=3&lang=2

- [6]https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2131716®=3&lang=2

- ANI News. (2025, December 19). US CPI inflation undershoots estimates; data distortion risk due to government shutdown: ICICI Bank: https://www.aninews.in/news/business/us-cpi-inflation-undershoots-estimates-data-distortion-risk-due-togovernment-shutdown-icici-bank20251219141108/

- https://www.hks.harvard.edu/publications/globalization-paradox

Deepa Bhaskaran is a strategic research and communications professional with 15 years of experience in advancing the Government of India’s initiatives through policy analysis and public outreach. She has authored policy papers on welfare schemes and India’s economic development. Views expressed are the author’s own.