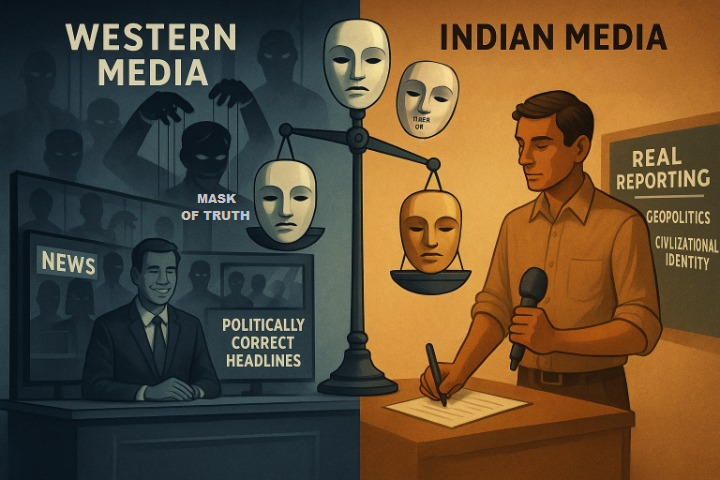

- While Indian media focused on the human tragedy and national implications, Western media veiled the attack in ambiguous language and avoided firm moral judgments.

- Western media outlets largely avoided framing the Pahalgam Terror attack as part of a broader pattern of cross-border Islamist terrorism, instead positioning it as an isolated episode in a long-running Kashmir dispute.

- Western media’s ambiguous language can dampen international support for India’s counterterrorism initiatives and dilute the global understanding of the Kashmir conflict.

- In the age of global terrorism, clarity of language and moral consistency in media narratives are not just ethical imperatives- they are strategic necessities.

Introduction

On April 22, 2025, a brutal attack occurred in Pahalgam, Kashmir, in which 26 civilians, most of them tourists, were killed by armed militants. The attack shocked the nation and drew widespread media attention in India and abroad. While Indian media unanimously labelled it a terrorist attack and linked it to cross-border terrorism, much of Western media adopted a softer tone, using euphemistic phrases like “militant violence” and avoiding clear identification of the perpetrators as terrorists. This essay examines the divergent media representations using critical journalism theories such as agenda-setting, framing, Hallin’s spheres, and Herman and Chomsky’s propaganda model.

Indian Media Coverage: Patriotism, Emotional Narratives, and Political Framing

Indian media responded swiftly and uniformly, condemning the incident as a terrorist attack. Outlets like The Hindu, Times of India, Republic TV, and NDTV framed the attack in the context of ongoing cross-border terrorism, with headlines such as “Terrorists Target Innocent Tourists in Pahalgam” and “Pakistan-backed Group Claims Responsibility.” Using the agenda-setting theory, Indian media placed national security at the top of the public consciousness.

As McCombs and Shaw argue, the media might not tell the audience what to think, but they certainly tell them what to think about. By emphasising the barbarity of the attack, the helplessness of the victims, and the repeated failures of international institutions to curb Pakistan-backed groups, Indian media ensured that public opinion was mobilised in favour of strong counterterror measures. The framing theory is also applicable: the Indian press constructed a clear moral dichotomy between innocent civilians and barbaric terrorists. Through emotional imagery and interviews with survivors and grieving families, Indian media played a role in uniting public sentiment across political lines, giving voice to a collective trauma.

Western Media Coverage: Soft Language, Strategic Ambiguity, and Downplaying Terror

In contrast, many prominent Western media outlets—such as Reuters, BBC, The Guardian, and The New York Times—covered the Pahalgam incident using deliberately softened language. Words like “gunmen,” “militants,” or “armed assailants” were favoured over the unequivocal term “terrorists.” Moreover, these outlets largely avoided framing the event as part of a broader pattern of cross-border Islamist terrorism, instead positioning it as an isolated episode in a long-running Kashmir dispute. This selective framing aligns with Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky’s Propaganda Model, particularly the “ideological filters” of elite interests and the tendency of Western media to report in ways that reflect foreign policy priorities of their home states. By underreporting the ideological motives of the attackers and avoiding attribution of terrorism, Western media arguably protected diplomatic narratives that prefer moral parity between India and Pakistan.

As Daniel Hallin described, the sphere of legitimate controversy helps explain this reporting style. Western media often categorises Kashmir within the sphere of “debate” rather than “consensus,” thereby framing acts of terror within a political dispute instead of as moral outrages. This approach can have the unintended consequence of relativising violence and obscuring the real victims—innocent civilians. The bias of omission is also evident. Many Western reports failed to note that the attackers separated women and children before executing men at point-blank range—an act designed for maximum psychological and political impact. This minimisation contrasts sharply with the extensive Western coverage of similar incidents elsewhere, particularly when involving Western nationals.

Many Western media reports failed to note that the attackers separated women and children before executing men at point-blank range—an act designed for maximum psychological and political impact.

Morality and Honest Reporting in Western Media: The Case of the Pahalgam Terrorist Attack and the Dharma of Indian Media in Times of Crisis

The terrorist attack in Pahalgam on April 22, 2025, which left 26 innocent civilians dead, exposed once again the troubling gap between moral responsibility and journalistic practice, particularly in the Western media’s coverage. The reluctance of major Western outlets to label the incident as “terrorism,” opting instead for vague terms like “militant violence” or “armed attack,” raises pressing ethical questions about journalistic integrity, global bias, and the selective application of moral frameworks. At the heart of journalism lies the moral duty to report the truth with clarity, objectivity, and accountability. However, when it comes to incidents like the Pahalgam attack, Western media often falls short of this ideal. This selective vocabulary—“militant” instead of “terrorist”—reflects more than linguistic caution. It indicates a calculated ambiguity rooted in geopolitical interests, ideological preferences, and legacy narratives. Edward Said called this the “orientalist gaze”—a tendency to patronise non-Western societies, deny their moral clarity, and downplay their suffering when inconvenient to Western diplomatic or strategic objectives.

Such selective reporting contradicts the journalistic codes of ethics professed by major institutions. The Society of Professional Journalists’ Code emphasises truth, minimising harm, and accountability. When Western outlets hesitate to name Islamist terror, even when civilians are targeted, they fail this standard. This failure not only distorts the moral clarity of the incident but also denies justice and voice to the victims, reinforcing a hierarchy of suffering, where only Western lives merit universal outrage.

In contrast, Indian media, for all its imperfections, demonstrated moral clarity by naming the act as terrorism, providing context, and connecting it to the larger threat posed by radicalised groups and cross-border agendas. However, Indian media too must reflect on its role and responsibilities. In times of national crisis, the media’s dharma (duty) is not to inflame passions or pursue political vendettas, but to uphold truth with sobriety, stand with the victims, and promote societal cohesion without compromising factual rigour. The Indian media must practice yukti (reason), karuṇā (compassion), and satya (truth) as part of its dharma. Sensationalism, over-nationalism, or biased reporting can fracture public discourse. But truthful, morally clear, and courageous journalism has the power to shape informed citizenry and resilient democracies.

The Pahalgam attack is a reminder that journalism is not merely a profession. It is a moral calling. Whether in India or the West, the media must rise above ideological filters and geopolitical calculations. The dharma of the media in a global age must be rooted in ṛta – the principle of cosmic and moral order. In the face of terror, obfuscation is not neutrality; it is abdication. Honest reporting, especially during a crisis, is not just ethical, it is the highest expression of democratic responsibility and civilizational strength.

Consequences of Divergent Reporting

These differences are not merely stylistic; they carry significant implications. Indian media’s explicit labelling galvanises public opinion and influences the state’s foreign policy and security posture. Western media’s ambiguous language, on the other hand, can dampen international support for India’s counterterrorism initiatives and dilute the global understanding of the Kashmir conflict. Moreover, these diverging narratives reflect media ethnocentrism, where domestic events in the West are prioritised and globally framed in ways that serve Western policy interests. When the victims are from non-Western states, and especially when those states are allies of the West only on paper, the clarity of journalistic condemnation often fades.

By avoiding terms like “terrorism” and declining to call out groups like the so-called “Kashmir Resistance,” Western media outlets indirectly contribute to the normalisation of such violence.

Critical Appraisal

While Indian media can be faulted for occasional hyper-nationalism and sensationalism, in this case, it remained consistent with international norms of terrorism reporting. The clear labelling of the perpetrators and contextualization within a pattern of attacks was accurate and necessary,y though there were a few exceptions. Conversely, Western media’s strategic ambiguity, underreporting of ideological motives, and overemphasis on the “complexity” of Kashmir reflect a troubling trend. By avoiding terms like “terrorism” and declining to call out groups like the so-called “Kashmir Resistance,” Western outlets indirectly contribute to the normalisation of such violence.

Proposed Model for Media Conduct in India During Crises: Balancing National Interest, Security, and Constitutional Freedoms

In a vibrant democracy like India, the media plays a vital role as the fourth pillar, shaping public opinion and safeguarding democratic discourse. However, during times of national crisis—especially those involving external aggression, terrorism, or breaches of sovereignty—the media must exercise its freedoms with enhanced responsibility. To ensure coherence between constitutional liberties and national security imperatives, a calibrated model is proposed here for media conduct. This model is rooted in the Constitution, guided by jurisprudence, and framed in a manner that is legally sustainable and ethically sound.

1. Constitutional Foundation and Legal Validity

The proposed model draws legitimacy from Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees freedom of speech and expression, and its reasonable restrictions under Article 19(2), which allow for curbs in the interest of the sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, and public order. This model respects media freedom but ensures it operates within constitutional bounds when national security is at stake.

2. The “Responsible Freedom” Framework

At the heart of this model is the principle of “Responsible Freedom”, which ensures that while the media retains editorial independence, it self-regulates with greater scrutiny in sensitive scenarios. The framework has three concentric pillars:

A. National Interest First Protocol (NIFP)

During cross-border strikes, terror attacks, or military operations, all media houses must abide by advisories issued by the Ministry of Defence and the Ministry of Home Affairs under an agreed NIFP charter. Live coverage of operations or sensitive locations should be deferred or blurred to avoid endangering personnel or civilian lives. Intelligence-related or unverified claims that may harm national interests or diplomatic relations must undergo a “security clearance gate” within the newsroom itself, guided by a certified editor trained in crisis reporting ethics.

B. Public Right to Know vs. Security Harm Principle

All reports must balance the public’s right to information with a harm-analysis principle. If a report may exacerbate violence, embolden adversaries, or cause panic, it should be postponed or rephrased without misinforming the public. The model encourages fact-based, source-verified reporting, with disclaimers when data is unconfirmed during fluid crisis situations.

C. Collaborative Oversight with Independent Audit

An independent National Media and Crisis Ethics Council (NMCEC) comprising retired judges, media veterans, and national security experts may be instituted (not state-controlled), whose role is advisory, not punitive, but with authority to issue censure notes for irresponsible conduct. Periodic crisis-reporting training and legal briefings for editors and correspondents will be mandatory, in collaboration with the Press Council of India and statutory law schools.

3. Judicial Sustainability

This model is inherently respectful of fundamental rights. It leans on the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence, such as Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras (1950) and S. Rangarajan v. P. Jagjivan Ram (1989), where the Court upheld the right to freedom with corresponding responsibility. The framework is voluntary but binding in principle, allowing the media to uphold its dignity while acting as a constructive force in national crises. It is thus a dhārmic model – just, balanced, and constitutional.

Conclusion

The Pahalgam terror attack of April 22, 2025, has revealed a profound divergence in the narrative approaches of Indian and Western media. While Indian media focused on the human tragedy and national implications, Western media veiled the attack in ambiguous language and avoided firm moral judgments. Using journalism theories such as agenda-setting, Hallin’s spheres, and the propaganda model, it becomes clear that these differences are rooted not just in editorial choices but in deeper ideological orientations. In the age of global terrorism, clarity of language and moral consistency in media narratives are not just ethical imperatives – they are strategic necessities.

Dr. Nanda Kishor M. S. is an Associate Professor at the Department of Politics and International Studies, Pondicherry University, and former Head of Geopolitics and International Relations at Manipal University. His expertise spans India’s foreign policy, conflict resolution, international law, and national security, with several publications and fellowships from institutions including UNHCR, Brookings, and DAAD. The views expressed are the author’s own.